For this special retrospective episode, producer Jeff Holmes sat down with Tyler to discuss the past year in conversations and more, including who was most challenging guest to prep for, the most popular — and the most underrated — conversation, a test of Tyler’s knowledge called “Name That Production Function,” listener questions from Twitter, how Tyler has boosted his productivity in the past year, and whether his book and movie picks from 2009 still hold up.

Want to support the show? Visit conversationswithtyler.com/donate. Your gift helps create enhanced transcripts like this one.

Watch the full conversation

Recorded December 11th, 2019

Read the full transcript

TYLER COWEN: I love going to a hotel, often a bad one, when all they have is cereal. And then I can have it again and I don’t have to feel guilty. And I won’t have it any other time.

JEFF HOLMES: Actually one of my questions for you Tyler was what your favorite packaged grocery store item is. So I know you love chocolate. But besides that, if you were buying a packaged good off the shelf in a grocery store, what’s your favorite thing?

COWEN: Well the funny thing is, I don’t really buy any packaged goods. So I hardly buy any canned goods. I love Goya small white beans. I cook them with chili and I love Goya small red beans. I cook them with Mexican dishes. But I’ll buy fruit, vegetables, meat, fish, cheese, and very little processed or packaged. I can’t even think offhand. If you count smoked trout wrapped in plastic, that’s a kind of package. But it’s still basically buying fish.

HOLMES: Yeah, so you follow the health advice where you stay around the perimeter of the grocery store and you’re in the fresh fruits and you’re in the meats, but you’re not in those interior aisles where they typically are stocking the candy bars and potato chips and things like that.

COWEN: That’s right. But I’m not sure it’s motivated by health. I just like the other items better.

HOLMES: But you said cereal. So is cereal one of those foods for you that you indulge in at hotels but you won’t buy it for yourself now?

COWEN: I don’t buy it ever. And I only indulge in bad hotels. Like if I’m staying in Menlo Park where the hotels are bad unless you’re paying a lot. And they’ll just have like cereal and bad eggs and bacon. I’ll just have the corn flakes. But it’s so delicious. And to do that five times a year makes me very happy.

HOLMES: A story known at Mercatus and is part of the lore of Tyler is that when you were studying in Germany, you had someone ship you cereal.

COWEN: That’s correct.

HOLMES: This is before you had your awakening. Tell us that story.

COWEN: I think you can get away more with eating cereal when you’re younger. But I had a favorite cereal which then was Product 19, and it was very hard to get in Germany. The only place you could get it was at American Army bases. And then you had to pretend to be part of the American Armed Services, which involved costs of its own. So, one very nice person working at Mercatus sent me a bunch of boxes of Product 19.

HOLMES: The first Mercatus export maybe in a way was Tyler Cowen and Product 19.

COWEN: That’s correct. To Germany.

HOLMES: So when was that? What year was that?

COWEN: That must have been 1984, possibly ’85. ’85 I think.

HOLMES: And when was your awakening in terms of food? So it wasn’t —

COWEN: In Germany. That was the year. So I was starting to experiment. I think I was 23 when I went. In graduate school. And then I got to Germany and everything was different. So if you’re thrown out of your status quo, you’ll experiment with many other things too. I think that’s an interesting general principle.

People don’t experiment enough with their own lives. And you’ll find yourself trying things that were not part of the initial experiment. And that’s what Germany did to my food life. So I started trying, say, Korean food, which I hadn’t had before. I don’t even know that it was that good in Germany, but I didn’t know. And it’s like, I’m not going to eat German food every day so let’s try Bulgogi.

HOLMES: I think my first Indian food was when I was living in Germany.

COWEN: How was it?

HOLMES: In my mind it’s the first time I had a curry.

COWEN: So it was pretty tasty.

HOLMES: Yeah. And it was one of my favorite things and I thought “this is amazing” and it just happened to be in Germany.

COWEN: Yeah.

HOLMES: So my experience bears that out a little bit too.

Some of the things you mention about physical space and experimentation are going to come up in this conversation. We’ve already gotten started. For those of you who don’t know, I am Jeff Holmes. I produce Conversations with Tyler. I am joined with our host, Tyler. And we’re going to do a year in review and talk about the show. But go beyond the year — it’s the end of a decade and we’ve never done this before, so I’m going to go a little further afield. If you like this segment, we’ll do it more. So let me know, let Tyler know. But I thought it was a great time here at the end of the year to look back on the state of the podcast.

So we’re going to do a few things. We’re going to look back at past episodes, and talk about them. We’re going to do a segment I like to call “Name That Production Function” which I am very excited about. And then I’ve actually looked back at Marginal Revolution from 10 years ago and I’m very curious to hear your thoughts about the productivity and the changes in Marginal Revolution in the past decade.

COWEN: I will fail all of the memory tests. I’m very focused on the next podcast, just to be clear. As my producer tells me to be.

HOLMES: Yes. Well that is the prime directive for Conversations with Tyler. But we’re here at the end of the year. Actually all of our episodes through the end of the year have been recorded but we do have always more in the queue, more in the pipeline. Your prep is as intensive as ever.

COWEN: How many total this year? Do you have a count?

HOLMES: Nearly 30.

COWEN: Wow, that’s a lot.

HOLMES: Starting last year we started releasing every other week and then we usually have a few bonus episodes. This year that was true to form as well. So we do minimum now about 26 and then usually there’s a few extra. And so as you look back over those episodes and you have the list in front of you, what strikes you about it? Can you keep up the pace?

COWEN: I think I can. I felt it was an incredible year. Our best guests, maybe the most diverse group, very few weak episodes. And for me, basically a thrill each time. People I thought I’d never have a chance to do a podcast with and here they are.

HOLMES: Have you had to adapt your research process to accommodate more guests? And I think we have more guests on that you’re not as familiar with that you can’t just rely on a base knowledge, you really do have to get in at a ground level. Not just read everything they’ve done, but maybe get more of the contextual work down. Have you adjusted or you just go for it and you’ve just had to shift other priorities?

COWEN: I’ve had to shift other priorities. Economists are the easiest to prep for. Like in principle, you can try doing it with no prep. Ed Boyden was one of the hardest, because he studies the brain. And even Ed will tell you, we don’t understand the brain. So if Ed doesn’t understand the brain, how well do you think I understand the brain? But I still have to ask him some questions. Knausgård, I had to revisit a lot of Norwegian literature, which I had already read, but that wasn’t actually very easy. That was an especially difficult prep. And anytime I have to read fiction, which I just read slower. I’s not the fault of the author. Neal Stephenson was a very difficult prep.

HOLMES: Long books.

COWEN: Long books. And you can’t just breeze through them because like you’ve absorbed the material in some other capacity. And then Jordan Peterson’s a hard prep. Not that he’s written that much, but there’s so much of him on YouTube. And you can only listen to it that quickly. And you’ve got to decide, what am I going to do about this guy? At some point you just drop it and you put your energy into thinking through, how should the conversation actually be?

COWEN: But the hardest prep of all was Emily Wilson who translated Homer. In a way that was mainly one book, but it was one book I had to read about five times. And it’s a very hard book. So that was like the single killer prep for me during the year. And that was very rewarding. But that was tough.

HOLMES: Let me give you a rundown of the stats. So do you have a sense of what was the most popular podcast this year?

COWEN: No idea whatsoever. Are you allowed to tell me?

HOLMES: Sure. I’m benchmarking this in the first week of release to —

COWEN: Okay, fair enough.

HOLMES: To control for episode age. But the most popular podcast in the first week was Jordan Peterson.

COWEN: Not surprising.

HOLMES: No, of course not. Jordan Peterson was by far the most downloaded in the first week.

COWEN: And that was closer to his popularity peak than today.

HOLMES: Yes. And I thought a very good conversation. Because I’ve reviewed the conversations leading up to this and I was surprised at how — as you say, Jordan Peterson’s a very exposed person. A lot out there. But I found a lot of what he said very good.

COWEN: And it was actually and conversation, which is not always the case, right?

HOLMES: That’s true. I thought his comments on fame and having to be careful, I thought he revealed something about himself that was very interesting. I encourage everyone, if you’re new, you should definitely check that out.

Do you have a sense of what might be the most underrated conversation? If you look here and you think about our typical listenership and one they may have skipped; I have my answers, I’m curious to hear yours.

COWEN: Most underrated. I suppose I think that’s going to be Knausgård, who was brilliant but highly literary and very much into things Norwegian. So my guess is that did not get the number of listeners it deserved. But I’ll defer to you. You’ve to the data.

HOLMES: I’m not equating it necessarily with listens, but that is true. I think Knausgård under performed relative to the quality of the conversation and how well he is known within literary circles. And for me, Knausgård was also a highlight. It was fun also just to record that. It was in London.

COWEN: He left his black bread and we got to eat it.

HOLMES: He left his bread.

COWEN: That was awesome. It’s like, “I’m eating Knausgård’s black bread!”

HOLMES: Yes. And there was a bag of pastries and we realized too late that he had left them. Apparently this is common for Knausgård — that he forgets things and leaves them behind.

COWEN: I should confiscate the food from all of our guests and producers.

HOLMES: We divvied it up amongst you, your wife, and myself and another producer who was sick and I don’t think got to enjoy it. One of those pastries I brought all the way back to the states and my wife even enjoyed one of Knausgård’s pastries. But I also loved that conversation because he talked about fatherhood and writing in a way that I found very affecting as someone with a young child. So even as someone who’s never read Knausgård, which is me, I thought it was a great conversation.

COWEN: The best part of that was his opening look, which is not on the audio or the transcript. It was clear he’s sick and tired of doing media. And he got the first question and his eyes shifted as he realized, this was going to be an actual conversation. And that was maybe the CWT highlight of the year for me, was to see Knausgård’s eyes shift and just how quickly and how smartly he realized that he was in for something different. It did not take him long.

That was maybe the CWT highlight of the year for me, to see Knausgård’s eyes shift and just how quickly and how smartly he realized that he was in for something different. It did not take him long.

HOLMES: Yes. In editing these we do take out pregnant pauses and people do stop to think. That’s something I know people wonder about, because sometimes the conversation seems so fast paced. And usually they are. But sometimes guests do take a moment and they think about something.

COWEN: Do I do that?

HOLMES: I don’t think so — [CWT audio engineer] Carter’s shaking his head no. I don’t edit them anymore. I don’t think we’re cutting out pauses for you as much and actually I think for guests it’s — they don’t have the time to regroup because you’re so fast. I’ve definitely heard that from guests. That the pace is thrown off for them. While we try to leave in a hint of when there was a pause, we do condense and tighten. So these people aren’t always super humans.

But I remember with Knausgård in particular — as I recall he did take quite a bit of time after that first question to think and that wasn’t reflected in the final product.

COWEN: So which is the most underrated according to you?

HOLMES: I would say, Knausgård and the other one I would say is Emily Wilson.

COWEN: I was going to say that, so we agree actually.

HOLMES: Yeah.

COWEN: And Emily was fantastic.

HOLMES: Yeah.

COWEN: But Homer is not the biggest draw with our audience. But she was perfect. She knows everything. There was something just mellifluous about the whole rhythm of the dialog.

HOLMES: And she is someone who has found a way to use Twitter effectively to market and story tell about her work as a translator. And she’s a great Twitter follow. So that’s an underrated aspect of Emily Wilson. So yeah, those would be my two top picks for underrated conversations.

As you look over, any other reflections on the year? Surprises for you? Like if you would have thought at the beginning of 2019 that we’re going to have some of these people on. Because some of them we know, some of them we don’t. They come very quickly.

COWEN: Well I didn’t think Mark Zuckerberg would ask me. That was a surprise. I said yes. That would be the biggest surprise. The physical setting of the chat with Alain Bertaud, where the World Trade Center had been. That overlook site where all of New York was around with the open windows. And as the chat proceeded, it turned to dark and the lights came out. Again, the listeners have no sense of that. But for me, that was pretty incredible.

HOLMES: Yes. We were on top of One World Trade Center for that conversation and we did it right at sunset and it was a special event for that reason. The subject matter, the setting. Kudos to our event producer for that. Caitlyn Schmidt, she did a great job.

COWEN: Margaret Atwood making fun of me and the art collection in Kwame Anthony Appiah’s home. Those are two other very memorable moments.

HOLMES: And that will come up. Actually I’ll use that to transition to a segment I’m going to slip in at various points in the conversation. We’re going to do Name That Production Function. So I’ve gone through — and obviously a recurring theme is that you ask about their production function. Sometimes explicitly, sometimes it just comes up organically where they talk about how they do what they do. So I’ve grouped them into different themes.

COWEN: Before you do that, I just want to say, it’s one of my core views. We should just study successful people more. Like how’d they do this?

HOLMES: Yes.

COWEN: And there’s a very superficial version of that in the media all the time. But like actually trying to figure out how they did it. To me it’s one of the most interesting topics.

HOLMES: Well on that question, when people give their production function, how much do you believe they’re aware of it? Let’s say for a CWT guest, how often do you think this is actually true or this is something they think, but is not the true production function?

COWEN: I don’t think it’s untrue. But I think on average they’re too modest and they’re not quite willing to express their sheer ruthlessness at being successful in a way. And the glee they take in that. So it’s a biased estimate, I would say.

HOLMES: Yeah. One of my things that I’m always curious to hear people name in a production function is the people that surround them, the team they’ve built. And sometimes it may be more of a leadership team, but sometimes it might just people who are very good at using producers, say. Or people like administrative assistants and how that plays into people’s production function and allows them to focus on the things that really matter. I know this is something that people talk about in academia some as well — that academics tend to get saddled with a lot of administrative work. But honestly, I think one of the underrated aspects of any person’s production function is the extent to which they can plug into an infrastructure and have certain things just not be a focus of worry for them.

COWEN: And Ed Boyden saw that. But a lot of our guests didn’t emphasize it. And I feel that’s another bias. By being excessively modest, they’re in some bizarre way also being too egocentric.

HOLMES: Yeah.

COWEN: They’re not talking about, like how am I good at building a team or letting someone else build a team around me.

HOLMES: Okay. So first theme in Name That Production Function. Several guests gave answers related to physical space. So the first one. “I have a very big desk from Ikea. I have a huge orange cat who’s mostly on it. I also have a couple of Greek dictionaries, Greek texts, notebook.”

COWEN: Sounds like Emily Wilson. But that’s a softball.

HOLMES: That’s a softball. So Emily Wilson really stressed having a big desk with a lot of texts around it.

COWEN: She translates Homer. You need a big desk to do that.

HOLMES: And a big orange cat as well.

COWEN: And a cat, yes. And the Greek dictionaries.

HOLMES: Okay, second person who emphasized physical space. “I almost always work on the column at the weekend in the living room of our house in another state.”

COWEN: In New Jersey. That’s easy. That’s Appiah.

HOLMES: Yeah. So he said I work for six or seven hours and he emphasized that he can’t do certain work in certain spaces. He has a study, but he doesn’t do any work there.

COWEN: Multiple locations are underrated. I have two offices. In Arlington, in Fairfax. I used to have three. And I work a lot at home and I work a lot now on the road. Including going to these podcasts. So that’s four different locations.

HOLMES: On that question particularly, physical spaces, working on the road, do you have any tips or tricks?

COWEN: It’s been maybe my biggest productivity boost in the last two years. I’ve learned how to work on the road much better. I think I was always pretty good at it. But now my productivity is maybe not even lower for most trips. So I’m not sure what I did to get there.

HOLMES: Is it preserving the schedule or is it you’ve just figured out how to do work in incidental spots as you’re traveling?

COWEN: More the latter and learning greater flexibility. So being able to write even if I’m just writing early in morning has been part of it.

HOLMES: Right. I feel like you have to go into two spaces. You either have to try your best to preserve a schedule even when on the road or you have to get much, much better at just working where you can and not being precious about it.

COWEN: And I’ve done the latter without breaking my rigid schedule at home.

HOLMES: All right, so we’ll go back to production function, but now we’re going to … Let’s do some listener questions. So I asked for some questions on Twitter. And I picked some of my favorites. This is still the conversation I want to have, so I did skip some.

All right, so we got some questions from Twitter. Here’s one. A former Mercatus scholar, make America boom again advocate, Eli Dourado. His question was simply, “What is it like being Tyler?” And this felt like an inside joke to me. I don’t know if it is. But I have an addendum to it as well. So answer that question and then my follow up to it would be, is there a difference in what it’s like to be Tyler from 2009 to now? How has it changed in the past 10 years?

COWEN: I think I’m very calm and it’s really quite rare that I have an unhappy day. It’s hard for me to remember one. So this extreme evenness of temperament is actually a real thing. I guess that’s what it’s like being Tyler. It has some down sides, but it’s great for getting work done because your emotions are not distracting you from the task in front of you and it just happens. So that’s part of what it’s like being Tyler.

HOLMES: I’ve never witnessed a Tyler tirade.

COWEN: I think you never will.

HOLMES: So I was a Tyler fan for many years, started reading Marginal Revolution in 2006, probably. And you know they say, “don’t meet your heroes.” That’s always a concern. But I would say you are exactly as you appear to be. And meeting you has been great and working with you has been great.

COWEN: Thank you for the kind words.

HOLMES: That you are exactly how I think most people perceive you to be. There is no other dark side of Tyler. There is no Tyrone lurking in the shadows.

COWEN: That’s a problem perhaps. But, I think it’s an interesting question. Whether you should aspire to be better or worse than your public self. And you can make an argument either way. So there are people who are just incredible when you read their writing. And when you meet them, there’s nothing wrong with them. But you don’t get anything extra out of meeting them.

HOLMES: Yeah.

COWEN: And I guess I feel that’s a worse way to be. That if the person is better than the product, maybe in some ways the product is worse. It’s easier to exceed a lesser product. But nonetheless, philosophically, that’s what I prefer in people, is for the person to be better than the product.

HOLMES: You have your product as writings and your thoughts that are out in the web, but I don’t think most people would consider you overexposed still or they feel like they’ve gotten to the depths of Tyler. And I think that maybe that time can come. Maybe there is a limit but I don’t think we found it yet.

COWEN: One thing Jordan Peterson figured out, it’s one thing that made him successful, is there’s a certain way in which on the internet you can’t be overexposed. That if there’s just a steady stream of you, it feels like being overexposed compared to the standards of 1987 or whenever, but in fact it’s not and people are picking and choosing. And you end up just dominating a particular space in a particular kind of way. And I think most older people have not made that transition mentally to understanding how you should exist intellectually on the internet.

HOLMES: I’m sure it does feel like that to a Jordan Peterson. I feel like in 2006, 2007, I could go on YouTube and watch literally every video that existed of you. And now I can’t. But I also choose not to watch some. I mean it’s amazing now if you had asked me 10, 12 years ago, oh there’s new Tyler content out. And I still love it and I read Marginal Revolution every day, but I also do that filtering myself that I like, well I still have my canon or the core reading that I do. Like one thing is, I almost never read your Bloomberg columns.

COWEN: Yeah, it’s fine. They’re for a different audience, which is not you.

HOLMES: Yeah. Well how do you think about that difference?

COWEN: If you think about Bloomberg, the first tier of readers are those people who subscribe to the terminals. And a most of them are a finance audience. They tend to be highly analytical, high income, with a particular set of interests. And I think it’s fine, great to write for them. I love them as an audience. But, they’re not like the blog audience or the CWT audience at all.

HOLMES: So you’ve got sort of a portfolio now, you feel?

COWEN: Yes.

HOLMES: How does the podcast fit into that? Do you feel like you’re reaching a new or a bigger niche? How does that sort for you?

COWEN: I mean, I don’t even know who I’m reaching. When people see me in public, they now mention the podcast more than the blog. So that tells me something. But part of the strategy is in a way to ignore the audience: “This is the conversation with person X that I want to have.” And it’s true. Because that’s the only reason to do it in a way. It’s not an income earner.

HOLMES: Should people approach you if they see you? Or do you-

COWEN: Depends who they are.

HOLMES: But if a listener to the podcast sees you in an airport or train station?

COWEN: In the current equilibrium, I’m happy when they do. But I’m not sure it would be true across all margins.

HOLMES: Do you have rules of etiquette that you want us to communicate here and now? Say hello but —

COWEN: Yeah, sure. No reason not to.

HOLMES: Celebrities have to learn the rules here about you can say hello, but maybe no photos. Do you have any of those?

COWEN: You know, whatever a person wants, so.

HOLMES: Okay, you heard it. Whatever you want.

COWEN: But no, in the current equilibrium. So this is a Lucas critique issue.

HOLMES: Well let us know-

COWEN: If you announce the current equilibrium is fine —

HOLMES: It’s already shifted. It shifted already.

COWEN: Yeah.

HOLMES: Okay, next question from Twitter. This is from Benjamin Fisher. “Does Tyler have any thoughts on the legacy of Robert Crumb?” Do you know Robert Crumb?

COWEN: You mean the …created the comic books —

HOLMES: Cartoonist.

COWEN: That the movie’s about. I’ve never really read them. I saw the preview for that movie many times and somehow it didn’t appeal to me. And I haven’t read comic books since I was a kid when I read a lot of DC comics when I was quite young. And my interest with it has died there. I’m not against it, but it just has not been a live thing for me, just like graphic novels are not a live thing for me. I love The Sandman series by Neil Gaiman, but most of them — just they don’t click with me somehow. The fault is mine, I would readily admit.

HOLMES: All right, we’re going to move off of listener questions and go back to production function. Here we go. All right, these are on writing habits. First one, “I’ve never written as much as I have after I got the children. After I started to write at home. After I kind of-”

COWEN: Knausgård.

HOLMES: Knausgård.

COWEN: The Norwegian.

HOLMES: And as I mentioned, this was a part that really struck home with me. He talked about trying to write and like literally lock himself in a Nordic lighthouse or whatever it was. But he established a routine in the middle of life and I liked that so much that I put that as part of the title. It became “less religious for him, less sacred.” All right, so that was Knausgård.

Second person, “I certainly do not write every day and I don’t think that’s a bad thing. I think it’s sometimes good not to be purposeful in what you’re doing, you’re distilling thoughts, there’s a lot of merit to allowing your thoughts just to meander in your head and make weird connections before you push them on the page.”

COWEN: I’m guessing a bit on this one, but Margaret Atwood?

HOLMES: That’s MacFarquhar actually.

COWEN: MacFarquhar, okay.

HOLMES: All right, next one. “When I first dreamed of being a writer, I thought I needed all these life experiences. I needed to go running with the bulls, be an alcoholic. Now I think just the opposite. There’s plenty of stories out there. The things to write about are all around you and you need to discipline yourself, get your health right. I tend to be very careful about what I eat. I exercise. Running, yoga, getting my body right. It’s not glamorous, but I feel like it benefits my work a lot.”

COWEN: Sounds like Neal Stephenson.

HOLMES: It’s not Neal Stephenson.

COWEN: It’s not?

HOLMES: Who’s your second guess?

COWEN: It sounds like a fiction author. Running with the bulls?

HOLMES: It’s not fiction either, because —

COWEN: Who else would need to … Ben Westhoff.

HOLMES: Yeah, it was Ben Westhoff.

COWEN: Okay, journalist.

HOLMES: Okay last one on writing. This was one of my favorite answers of all production function answers. “I could not do what I do if I was not zealous in managing high quality inputs into my mind every day in my life. That’s why I spend maybe two hours a day writing, I’m a writer…”

COWEN: Sounds like me.

HOLMES: “…but I spend three to four hours a day reading and two to three hours a day listening to music. People think that’s creating a problem but I say no, this is the reason I am able to do this, because I have constant good quality input. That is the only reason I can maintain the output.”

COWEN: I think only Ted Gioia would mention so many hours of music.

HOLMES: Yes.

COWEN: But it is also me. That would completely apply to me.

HOLMES: He articulated something I think is very true of infovores generally, but I haven’t heard it I think on CWT yet is that idea that saving the time for the inputs is what allows you to do the thing.

COWEN: That’s right. And music always having a role in what’s going on as well.

HOLMES: Okay, back to some questions and we’ll move on from production function. So EV fellow Lama, she asked what cuisine would you serve if you had a restaurant?

COWEN: I think it would be food from central Mexico and I would cook it. That’s my favorite food to cook. Like chicken mole is my best dish I think.

HOLMES: How long does it take you to make a mole?

COWEN: I’ve gotten it down to about an hour’s worth of labor time, but it has to sit overnight so it’s not ready in an hour. But if I rush and do it perfectly, my part of it is done in an hour and then the sauce sits overnight and then the next day the chicken roasts for about an hour and five, hour and 10 minutes. So it depends what you count. But it feels like it takes an hour.

HOLMES: And what style is it? Is it like a chocolaty mole?

COWEN: Chocolaty mole.

HOLMES: Another question from Mercatus scholar Emily Hamilton, who works on affordable housing, land use: “What do you think of fast casual architecture?” Have you heard that term?

COWEN: I don’t think I know the term. What does she mean by that?

HOLMES: Think of something like the Wharf in southwest D.C. where it’s a big master plan. It’s kind of this upper middle class development. They bring in a lot of higher end retailers. You might have a Whole Foods. You might have some fancy restaurants. And it’s all kind of part of this master plan, part of an urban design.

COWEN: I find so much of America dispiritingly ugly. But I’ve learned to prefer that. That it keeps our minds open for other things. And the towns that are in a way picture perfect, like Ghent or Bruges or Bergen, Norway where I just was. That’s stultifying. So I guess I quite like fast casual precisely because I don’t like it. That if architecture is what is controlling your mind rather than music, I suspect you’ll end up in a worse place.

You don’t want your visual physical environment to be too perfect in any one dimension, that that ends up stopping or halting your thinking in some way. So to grow up in Paris maybe now at this point is limiting. I’m not saying it always was, but Paris is a completely static city at this point. At least central Paris. It’s like my goodness, it somehow can’t be good for a public intellectual.

I find so much of America dispiritingly ugly. But I’ve learned to prefer that. That it keeps our minds open for other things. And the towns that are in a way picture perfect, like Ghent or Bruges or Bergen, Norway where I just was. That’s stultifying. So I guess I quite like fast casual precisely because I don’t like it. That if architecture is what is controlling your mind rather than music, I suspect you’ll end up in a worse place.

HOLMES: Another Twitter question. This is from Vincenzo Luna. “What’s the biggest change in the shortest period of time you’ve ever witnessed something either personally or professionally?” And he says, “To clarify I mean, anything from a near instantaneous transformation or something that preceded incrementally but you saw it from start to finish and you thought wow, that was amazing.”

COWEN: Well the growth of China would be one example. I’m not sure I can rank anything as the very most extreme. But I first went to China 30 years ago and I’ve been there many times since. And each time I go my jaw drops. And the difference between 30 years ago and today — I even wrote a Bloomberg column about that you didn’t read. But, the point got made. It’s really quite phenomenal.

HOLMES: Yeah. That is one of my regrets is that I haven’t visited China and the idea that you can see things changing almost in real time.

COWEN: That’s over there now. I mean it will still change a lot, but not at 10% rates of growth.

HOLMES: Back to production function questions. These are more grab bag. “My father always told me, when you travel you don’t look enough. Every time he traveled a lot, he would say, I have not looked enough, I’ve not looked enough. This was ingrained in me all the time.”

COWEN: I think I have no idea on that one. But maybe Alain Bertaud.

HOLMES: Alain Bertaud, exactly.

COWEN: That was a guess.

HOLMES: He emphasized that he would travel with his dad for business and his dad would more or less give him a mp and say, here’s some places to go. And he would report back and his dad would almost quiz him on what he had seen. And he always got critiqued for not looking carefully enough or noticing enough.

All right, here’s another one. “I keep a calendar of future plans. Many people do, but then I also keep a calendar of the past which logs how long it actually took for me to write that grant or to meet with that person or eat dinner or whatever. Over time I’ve learned a lot about how long it takes me to do something.”

COWEN: Is that Ed Boyden?

HOLMES: It was.

COWEN: Who else writes grants right? He has a lab. So that’s how I figured that one out. Not memory, induction.

HOLMES: Boyden has a lot of great tips in his. I could have selected any number of things but —

COWEN: He was one of the best for actually understanding how he succeeded.

HOLMES: Yes. And great insights into how you try to solve a problem, how you get a team to work together. Especially for an academic but even just in terms of the full roster of CWT guests, I thought he was great on that stuff.

COWEN: And I suspect the unedited Ed Boyden would be so much better yet. On administration, personnel management, working within a university, my goodness. The things he could say.

HOLMES: All right, let’s go to another theme in production functions. Interestingly two of our guests mentioned voice recording. First, this is literally all this person said about it. They didn’t elaborate:“I use voice recognition software.” And you were asking about how they produced their work. This was very recent.

COWEN: I don’t think I have any idea who uses voice recognition software. Who is it?

HOLMES: It’s Daron Acemoglu. And he gave it as an aside and it wasn’t dwelled on or elaborated on, but that’s what I keyed in on is that he said he basically — it sounded like he actually drafts his papers by dictating.

COWEN: By talking. Gordon Tullock did that of course.

HOLMES: Yeah.

COWEN: With a tape recorder, not with software. And then he would have someone type it out.

HOLMES: On that note, second person. This person said they write in the morning and they stop at about 11. “As I’m walking around for the next 15 minutes or so, sentences will come into my head, by and large they’re the best sentences so I’ve learned to carry a recorder with me. Now it’s just the voice recorder app on my phone. Because I know that if I jump in the car an start driving somewhere, I’m going to have a few of those lines and I don’t want to lose them.”

COWEN: Is that Russ Roberts?

HOLMES: No, that was Neal Stephenson.

COWEN: Neal Stephenson, okay.

HOLMES: Which I thought was great that his mind is still working and he leaves the work but he knows some stuff is going to spit out.

Do you find yourself having to write notes or —

COWEN: No, I don’t write notes.

HOLMES: Yeah. You just sit down and you write and when you’re done, that’s it. It’s a discrete kind of thing.

COWEN: If I need to remind myself of something, I’ll send myself an email. Which is the worst possible way of managing your production function. But it works. To use your inbox as a to do list. I think it’s actually underrated. So I’ve read all the critiques. I don’t need to email myself much. It’s maybe one thing every three days, and the rest I just remember.

HOLMES: One of my insights about you. I don’t know if you would agree with this but, when I email with you, you’re very responsive generally. If you’re near a computer you’ll respond nearly instantly.

COWEN: Yes.

HOLMES: And then often there will be a flurry of emails as if a real time conversation were happening. And for me oftentimes it feels like we’re actually texting with each other. But you never text.

COWEN: I never text. I’m against texting.

HOLMES: You’re against texting but here’s the thing Tyler, you email like a texter.

COWEN: But when you’re emailing you can type and when you text you have a little phone, you have big thick fingers, it doesn’t make any sense to me.

HOLMES: I actually, because I’m on a Mac, I can text from my laptop and I actually text a lot from my keyboard.

COWEN: Well then it’s like emailing, that’s fine.

HOLMES: So if I got you hooked up with the technology, maybe you could be texting like a teenager.

COWEN: I don’t see the advantage. Because with texting you’re in essence telling people they can jump a particular queue. And I’m not sure why you would want to give them that right, rather than reserving yourself the ordering privilege for the emails.

HOLMES: Right.

COWEN: So I always have my iPad and iPhone with me. So I can have as much immediacy as I want. And why let people jump the queue?

HOLMES: Right. Yes, this is the bane of texting, of Slack. It does create a presumption that you’re at the head of the line.

COWEN: Now responding to all your emails right away as I do, also creates that presumption. But somehow it feels different.

HOLMES: A few people talked about using social media as a tool. So we’re still on production function. So first person. “I would say I read widely. I play with a lot of ideas, most of which don’t come to fruition. Again, this is one of the advantages of social media.”

COWEN: Henry Farrell.

HOLMES: Henry Farrell. And he talked about doing little micro threads on Twitter as a kind of experimental thing.

COWEN: And he’s very good at that, yes.

HOLMES: Yep. All right, second one. Killing me, I’m losing my …

COWEN: You need to send yourself an email.

HOLMES: That’s right. Okay, second one. “That’s what I mean when I say spending time on Facebook is really part of my work. I try to have a sense of the temperature of the air, the flavor of the conversation. That’s where social networks used strategically I think, are extremely useful. It’s the kind of research tool that I didn’t have as a young journalist.”

COWEN: Masha Gessen. Of course.

HOLMES: I gave you the clue there at the end.

COWEN: But even without that I would have known. I remember that passage quite well.

HOLMES: I thought it was interesting that her friend described her as an empty pot. That she absorbs information and then it leaves her. Do you find that true of yourself? I mean I think most people would say no, you’re a sponge and you keep it all in.

COWEN: No I feel I don’t retain hardly any of it. That I can somehow summon it back if I cram on something. But at any moment I feel like I know nothing or close to nothing.

HOLMES: It’s deep in there but you have the tools to — you can’t access it offhand, but if you focus on it somehow that you know it’s there.

COWEN: It doesn’t feel lost, but it doesn’t feel on the tip of my fingers either.

HOLMES: All right, last one. This is a random one. “I played a lot of poker in college and I think I learned more about life and business from that than I learned in college. I would not say I’m a great poker player, but I’m pretty good. The thing that makes me I think good about that is getting good at quickly evaluating risk.”

COWEN: It’s got to be Sam Altman, right?

HOLMES: It is.

COWEN: Yeah.

HOLMES: Sam Altman. Who’s production function most clearly mirrors yours, do you think? Of these guests?

COWEN: Maybe Ted Gioia.

HOLMES: Yeah.

COWEN: But I like Sam’s quickness and emphasis on speed. Also his way of thinking about other people. So I felt I had more in common with him than maybe I was expecting to.

And a kind of do it right away obsession with speed. And how he evaluates other people by their speed I very much sympathized with. It was one of my favorite parts of that discussion. Just how quickly do they respond to their email?

HOLMES: So Altman brought up that as a founder thing. Do you have any sense of a pattern among … You send out a lot of invites to Conversations with Tyler and generally email with some of these people. So who are the speed responders?

COWEN: I don’t think I remember. Russ Roberts perhaps. Mark Zuckerberg. But I think … If it’s younger people and you don’t know how to evaluate them, but obviously it takes on greater weight in your impression. And it’s kind of an arrogant, like why shouldn’t you respond to me right away? But I think it’s true. And it’s fine if they want to downgrade me. I don’t take that personally. Like they’re going to do something else. But then I figure, I should downgrade them and that’s the equilibrium.

HOLMES: Very well. Some more questions from Twitter and then we’ll go back in the decade a little bit and look at Marginal Revolution through the years. Actually just one year, 2009. New Recusant on Twitter: “What econ related facts surprised Tyler the most in the last decade? Bitcoin, China?” What surprised you?

COWEN: Bitcoin surprised me multiple times. China I thought would have an excess capacity debt crisis and it didn’t. So those would be two big picks. That the rate of unemployment fell to such a low rate definitely surprised me. Those would be the three big ones that come to mind right away. Trump winning. Not an economics thing, but it surprised me, sure.

HOLMES: Looking back over the last decade — I went back and I looked at every post from December 2009. Partly to look at your end of year list because I think people would — I’m going to bring up some of your recommendations from December 2009.

COWEN: Okay, we’ll see how they held up.

HOLMES: Do you remember what you were writing about in December 2009?

COWEN: Well not month by month, but I know that time there was plenty on the financial crisis of course.

HOLMES: Sure.

COWEN: And I think the blog, like 2005 to 2010 or so was very different than the blog today. And I do understand, I think those differences.

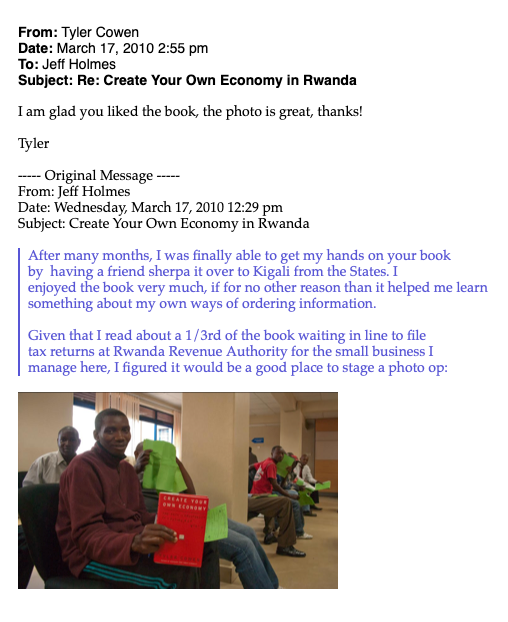

HOLMES: So 2009 for you, the book that you had published was Create Your Own Economy, which was renamed in paperback to Age of the Infovore.

COWEN: That’s right.

HOLMES: Is that your only book that’s been rebranded like that?

COWEN: As far as I know. The original title was bad, so I’m glad they renamed it. But it’s a sign of failure in a way.

HOLMES: I bought it with the original title and I was living abroad at the time and I had it shipped to me. And I emailed you.

COWEN: Did I respond quickly?

HOLMES: You did. I checked it last night. You responded within two hours. I’ll screenshot it for the transcript. I was living in a place where it wasn’t easy to get a book. I couldn’t go to a bookstore, let’s put it that way.

COWEN: Oh this was from Africa.

HOLMES: Yeah. It was from Rwanda.

COWEN: Oh so that was you. I remember that email.

HOLMES: Yes.

COWEN: But I didn’t know it was you. Amazing.

HOLMES: That was me.

COWEN: Okay.

HOLMES: And I was read a third of the book paying taxes in Rwanda.

COWEN: My opinion of my own memory just went up.

HOLMES: That’s good. Yes.

COWEN: My opinion of my own laterality just went down.

HOLMES: When I look over your posts from 2009, what struck me is some of it feels sort of old blogosphere, old internet in the sense that some of the links are broken, some of the blogs don’t exist. But I was struck by how many of the themes to me felt still very topical. Obviously there was credit crunch. You and Alex talked about Avatar because it was the biggest movie that came out.

COWEN: Yes, which is bizarre. Completely falling down a memory hole. Although they’re going to do like five sequels, right?

HOLMES: Yes.

COWEN: I don’t understand that but I will go see them.

HOLMES: So there is some of that, but what struck me is, yeah, the consistency. So you’re referencing Scott Sumner. I’m sure there’s-

COWEN: Scott’s now at Mercatus, of course.

HOLMES: And Scott’s now at Mercatus. There’s like a Henry … There’s probably like a Henry Farrell Crooked Timber thing in there somewhere.

COWEN: And he’s now done a CWT, yeah.

HOLMES: Yeah.

COWEN: The real lesson is the supply of bloggers is inelastic, right? And what should we infer from that? I’m not sure. But it’s significant.

HOLMES: Well, I’ll get to this now. So Alex has a post discussing Paul Romer, who we’ve had on and won the Nobel Prize.

COWEN: Yeah, the year before.

HOLMES: Last year. And talking about how the average age of people who are getting grants is going up and he wonders if that’s the reason why there’s a slow down in productivity or progress. Which I thought was very funny. There was also a weird coincidence in that December 2009 Paul Samuelson had just died. Paul Volcker as we’re recording this has just passed away.

COWEN: That’s right.

HOLMES: One thing that surprised me is that, I was clicking through the posts and I was going from December 31st back, and I clicked to like the second page of posts and I still wasn’t even to Christmas. And the output I thought was much higher. And I looked and on MR in December 2009 you had about 160 posts. So you were posting like five times a day, between you and Alex.

COWEN: Right.

HOLMES: This month, it looks like you’re on pace maybe to do about 130.

COWEN: So that’s four a day.

HOLMES: Your productivity slowed down and what are your reasons? Is it age or do you have other explanations?

COWEN: No, it’s on purpose. I’m doing more other things including the podcast. But I think in 2009 I was still experimenting in some fresh way with blogging as a new medium and what it meant. In some ways the blog was better than for that reason. Whereas now, Marginal Revolution, it’s a bit like, well, the Economist magazine plus a dose of me. And that’s a set formula. I don’t know that there’s that much more experimentation I can do or should be doing. Maybe that drains a little bit of energy out of it. But people know what to expect more and I think that’s the biggest difference.

HOLMES: My explanation too would be this was really before Twitter took off and so I would think that some of those marginal posts are now just tweets.

COWEN: That’s right.

HOLMES: You used to have a segment called The Best Paragraph I Read Today. I don’t think that you would do a lot of that anymore. You still do to some extent, but I think a lot of that would actually just be a tweet today and not a post.

COWEN: And if you think about the transcripts behind a CWT, and they go on the blog, they’re like equal to a lot of posts. And so are Bloomberg columns. They’re 800 words typically and that’s longer than an average post. So people have to click. But I think if you adjust for that, the amount of material is not really down at all.

HOLMES: Okay. So the rate of progress, the rate of productivity for Marginal Revolution, for Tyler Cowen, Alex Tabarrok?

COWEN: It’s presented more economically, but has not fallen.

HOLMES: Okay. Let’s get into some of the recommendations. So it’s become more of an institution for you. Interestingly, you do have recommendations, but they’re more offhand. They’re a little flip. When you talk about movies, you say these are what come to mind, whereas I know now you actually catalog it and you try to keep a list running through the year.

COWEN: That’s right.

HOLMES: Do you have any sense-

COWEN: I don’t try to keep a list, I keep a list. Right?

HOLMES: Yeah.

COWEN: There’s a big difference.

HOLMES: Yes. You keep a list. I’ve seen it. I have access to the Marginal Revolution draft posts and I see it in there. And I do peek because I’m always curious. Let’s do movies first. Do you have any sense in 2009 what your favorite movies of the year were?

COWEN: No idea whatsoever. And what movie was exactly which year. Other than Star Wars, I’m not sure there’s a single movie I could tell you, or just a small number.

HOLMES: So the list you gave was Tyson, which I don’t even know what that was. I didn’t look it up. Tyson, I Love You, Man, District 9, Up, the Pixar film, Brüno, Let The Right One In, The Hurt Locker, and the documentary Man On Wire.

COWEN: District 9, Let The Right One In, and Man On Wire have aged the best on that list. And Brüno probably has aged the worst. It’s still a good list I think.

HOLMES: Yeah.

COWEN: Of course what you could see then was a bit different than what you could see now. It was pre-Netflix. So the list would be different now. There would be more movies from the year before on Netflix disk now.

HOLMES: Fiction. You say, “My favorite works of fiction this year were the new Pamuk…” Orhan Pamuk who comes up when you interviewed Dani Roderick, Daron Acemoglu.

COWEN: Sure. That was still a good pick. Yes.

HOLMES: The Museum of Innocence was the book.

COWEN: Right.

HOLMES: Gail Hareven’s The Confession of Noa Weber.

COWEN: I met her this year. She was phenomenal. I loved meeting her. I was very honored. Natasha and I were in Israel and we made a point of contacting her and I still love that book. A great pick.

HOLMES: And A Happy Marriage, by Rafael Yglesias.

COWEN: Who is an extremely underrated writer. He’s the father of Matt. And more people should read him.

HOLMES: Speaking of the old blogosphere, and who is obviously still continuing at Vox.

COWEN: And Dr. Neruda’s Cure for Evil is maybe Rafael’s best book. And he has a new one online, which I haven’t read yet and I’ve been meaning to. I wish he would get more attention.

HOLMES: For nonfiction you said, “the new Gabriel García Márquez biography”, which I don’t know what the title of that was. The link was broken and I forgot to look it up. Do you remember offhand with that biography?

COWEN: Not the exact title, but a good book.

HOLMES: Chris Wickham’s The Inheritance of Rome.

COWEN: Yes. Good pick.

HOLMES: Eric Siblin’s The Cello Suites: J.S. Bach, Pablo Casals, and the Search for a Baroque Masterpiece.

COWEN: I feel very good about my old picks, I have to say.

HOLMES: I bought The Cello Suites on that recommendation. I read it with my now wife. And we had a great time reading it together. I’ve bought many books off of Marginal Revolution as I suspect listeners have.

So you feel good about your picks?

COWEN: I do. At least from 2009. The cinema, like one or two of them are off and all the others still seem kind of perfect.

HOLMES: Okay. Do you feel —

COWEN: It’s interesting that cinema picks are more uncertain about how they hold up over time. It makes intuitive sense, but I’d like to have a good theory as to why that is.

HOLMES: Well something like Avatar, which is the biggest movie of the time has been, as I think it’s been noted on the Marginal Revolution, just completely disappeared from the cultural consciousness. We know the sequels are coming, but beyond that.

COWEN: But I feel if I saw it again, and maybe I will, I wouldn’t say, “Gee, how could I have liked that?” It would feel like, “Gee, that was some weird, but brilliant dead end.” And a lot of wonderful movies should be weird but brilliant dead ends.

HOLMES: What’s fascinating is I think it was Alex [actually Tyler] linked to a post of a think piece on Avatar and it was about white privilege and I just thought that that was so funny because it felt like such a present day take on Avatar, but it was actually happening in 2009.

COWEN: Blue privilege.

HOLMES: All right, so looking forward, 2029, are you still blogging?

COWEN: Yes.

HOLMES: Are you still podcasting?

COWEN: 10 years from now, probably not. But it’s possible. I’m not quitting anytime soon. If you said five years, I’d say, “Oh definitely.” 10 years, hard to say. My voice might give out.

HOLMES: We’ve often talked about this, you and I, that the power CWT listener is actually a reader. That they read the transcript. You yourself don’t listen to podcasts actually. Do you have any that you ever listen to — Maybe you have to for some reason.

COWEN: No. Sometimes I have to and I don’t mind, but I never want to listen to any podcast, including my own. It’s just too slow. And I’ll listen to podcasts when I’m prepping for a guest and then I “have to”. But that’s it. So I have no idea who really has a good podcast.

HOLMES: So given that you don’t listen to them, a lot of our sort of most successful listeners don’t listen to it, they read the transcript.

COWEN: But most don’t offer a transcript. So what they do with other podcasts, I don’t know. Some people have their own transcripts made.

HOLMES: Right. But does that mean that podcasts themselves are overrated in a sense? And that writing and the written word is still underrated?

COWEN: Yeah, the whole genre mystifies me. I don’t see why anyone does it or listens or cares. It’s bizarre given that I produce the output. But I never would have predicted it. And it always feels to me like a bubble. I don’t think it is at this point. It’s less of a bubble than blogs were. I think the big insight was that people were wasting their time a lot more than we thought and mobile and social media and podcasting all filled that space.

HOLMES: Yes. I think it is a way to fill up some of that idle time with content that actually is better than what you’re typically going to consume. To the extent that we’re competing with mobile games, which I think is one of the things you’re going to do with your idle time for an average person.

COWEN: I feel our audience listens and reads, but podcasts as a whole I wonder is it just like some kind of drone in the background like muzak? Muzak with a human voice. I don’t know.

HOLMES: I’m sure some people listen to it that way. For me, it’s actually replaced music, which may not be a good thing. But I stopped — this back in iPod days. I’ve been listening to podcasts for a long time and it just replaced a lot of the music that I might have been listening to.

COWEN: I feel music is a dynamic influence on ourselves. And when music gets replaced we should worry. And music can change and you listen to different kinds of music. And there’s a repulsiveness to it that the spoken voice doesn’t have. So you’ve made me more worried.

HOLMES: But at least for the next year we’ll keep it going. Maybe five years, we’ll see.

COWEN: No. I don’t mind inflicting the human voice on people. I’m happy to corrupt them and tear them away from beloved music. But viewed aesthetically, if you think of say the 1960s and ’70s, music was primary in that era and there was something very creative about that. And that was a time when we made a lot of big, bold decisions, not all of them good ones. But nonetheless. And maybe the drone of the voice in the background reflects the complacency of our time. And podcasting is a form of complacency maybe.

HOLMES: On that happy note, let’s wrap up.

COWEN: And look forward to another year and more of working together.

HOLMES: That’s right. I’ve enjoyed this. I have enjoyed this and for those of you listening, please do let us know if you did too, we’ll do it more.

But before we close, I’d like to shoutout the other people at Mercatus who work behind the scenes on this, Dallas Floer, Carter Woolly, Sloane Shearman, Ashley Schiller, Krista Chavez, Kate De Lanoy, Kate Brown, Caitlyn Schmidt, Karen Plant, Christina Behe. For all of us, this is just one of the things we do at Mercatus and it’s a lot of fun.

COWEN: And just everyone else at Mercatus. The people who do infrastructure, the IT people, the finance people, the receptionists. They all do their bit. A guest shows up, how do they get back to the studio right? Someone does it. It’s not always us.

HOLMES: It’s part of the production function.

COWEN: That’s right.

HOLMES: Unheralded. But on behalf of Tyler, this is Jeff Holmes, thank you-

COWEN: And you’re all great to work with.

HOLMES: Thank you Tyler.