What is Karl Ove Knausgård’s struggle, exactly? The answer is simple: achieving total freedom in his writing. “It’s a space where I can be free in every sense, where I can say whatever, go wherever I want to. And for me, literature is almost the only place you could think that that is a possibility.”

Knausgård’s literary freedom paves the way for this conversation with Tyler, which starts with a discussion of mimesis and ends with an explanation of why we live in the world of Munch’s The Scream. Along the way there is much more, including what he learned from reading Ingmar Bergman’s workbooks, the worst thing about living in London, how having children increased his productivity, whether he sees himself in a pietistic tradition, thoughts on Bible stories, angels, Knut Hamsun, Elena Ferrante, the best short story (“Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius”), the best poet (Paul Celan), the best movie (Scenes from a Marriage), and what his punctual arrival says about his attachment to bourgeois values.

Watch the full conversation

Recorded March 15th, 2019

Read the full transcript

TYLER COWEN: Hello. I’m here today with Karl Ove Knausgård, one of the great writers of our civilization. He also has a new book coming out — which I enjoyed very much — called So Much Longing in So Little Space: The Art of Edvard Munch. Karl, thank you for coming.

KARL OVE KNAUSGÅRD: Thank you for inviting me.

COWEN: In book six of My Struggle, you mention René Girard and that mimesis is a useful concept for understanding human behavior. How do you think about who or what you’re trying to copy?

KNAUSGÅRD: Who I’m trying to copy?

COWEN: Yes. If you believe in mimesis.

KNAUSGÅRD: That was a tough first question, I have to say. How can I have come to that? I think there’s several levels you could reply to that question.

COWEN: Sure.

KNAUSGÅRD: First level would be whatever’s related to literature, to the art of fiction — how to tell a story — which is something you learn through reading. And you have to have that for writing. There are several ways to tell a story, several ways to enter a scene, several ways to write realistic prose. For me, almost all reading I’ve done has, I think, subconsciously sunk into me in my own world and in my own writing.

When I, for instance, read Marcel Proust for the first time, I absolutely loved it, and I read it like I was drinking water or something. But I wasn’t aware of me soaking it up at all, and I couldn’t write at that time. Two years later, I wrote a novel. It is incredible — many similarities with Marcel Proust, but I wasn’t aware of it. It was just something that happened. That’s one level of mimesis.

The other level is the opposite. It’s unlearning everything you know to be able to access what I like to think of as the world — the world we live in — because sometimes fiction can be so mechanical and so locked into certain ways to look at the world that it’s more like you’re looking through literature than through the world.

That was what I was struggling with in My Struggle: trying to find a language for my experience of the world and not . . . I wasn’t interested in writing a novel. I was interested in trying to get the language from my experience of the world.

And I think that is the key to Edvard Munch — what he did as a painter. Very much so because he grew up in Norway at the end of the 19th century in a kind of a certain pictorial language, which was realism, which was naturalism, and which was a national romanticism. You know, the glossy images of mountains and flowers and that kind of thing.

COWEN: Yes.

KNAUSGÅRD: That was what he had available when he started. He wanted to paint. That was what he had available.

COWEN: And he described his art as an act of confession, as you know. Is that true of yours? Are you fundamentally in the confessional tradition?

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah, I think so. But what Munch wanted . . . I think what Munch had was some experiences, very strong experiences. He lost his mother when he was very young, and then he lost his oldest sister, which was even harder for him. I think what he lacked when he started to paint was a language to express that. Couldn’t do that through glossy, nice romanticism. So he had to break down everything he knew about painting to try to get that through what he had experienced.

That’s the same thing with writing. That’s what you want to do — get that personal experience. The thing that only you feel. The thing that only you see. The thing that you know. Get that through. If you do that, you realize, “No, that’s how everyone sees it. That’s how everyone feels.” But that’s kind of the thing you have to try to reach, to tap into.

When I started to write My Struggle, I didn’t know that existed. I just wanted to do it for my own sake, more or less. And yeah, it was confessional.

COWEN: I reread a lot of your work in the last few months, and what struck me more is what a — in a sense — conservative writer you are. At first, I thought of you as a radical. But if you think of this long-standing pietistic, religious tradition of self-scrutiny, you have Rousseau, Goethe, even Swedenborg, August Strindberg. I now see you as very much in that tradition — that you’re the next Nordic confessional, and quite religious as a writer, in a way.

Would you accept that characterization?

KNAUSGÅRD: Pietistic I will accept, and a part of that Nordic tradition I will very much accept. Religious? That’s a bit more difficult to relate to, I think.

COWEN: But you wrote a whole book about angels, and it’s striking: Swedenborg, Strindberg — they were obsessed with angels.

KNAUSGÅRD: Yes, true.

COWEN: You’re obsessed with angels.

KNAUSGÅRD: Yes, true.

COWEN: Why the combination of angel obsession and confessional from the Nordics, including you? What’s the unity there?

KNAUSGÅRD: The obvious thing in regard to that is that a pietistic Christianity is a very personal relation to God, a very intimate relation to God — much more than a collective play like a religion as Catholicism would be. Much more internal than external. And as a novelist, that’s the confessional path, so to speak. But these things you don’t think about. These things you just do.

If you are born into a culture, that culture becomes part of you. That language becomes part of you. And something of that you have to challenge. Something of that you are not aware of. It’s just part of you. There’s certain writers I do really love, and I think that is part of my culture. And I think I’m similar to them because of many different things.

But these things you are talking about is kind of more cultural, deep-layered things, the pietism. These are not things you think about. This is things that just happen, I think. But it’s very un-modern. That’s true.

COWEN: Yeah.

KNAUSGÅRD: It’s very old-fashioned. That’s true.

COWEN: Exactly.

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah.

COWEN: Arnold Weinstein has a book on Nordic culture, and he argues that the sacrifice of the child is a recurring theme. It’s in Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling. It’s in a number of Ibsen plays, Bergman movies. Has that influenced you? Or are you a rejection of that? Are you like Edvard Munch, but with children, and that’s the big difference between you and Munch, the painter?

I told you we ask different questions.

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah, yeah. You just said different. You didn’t say difficult.

Yeah, because there was a lot of grouping together. Here you had Kierkegaard and the sacrifice of Isaac and the biblical story, which basically is a story about faith, and what it is to believe in God, and what it demands to believe in God — the completely irrational level it takes to believe in God. The leap out in the unknown which you have to take.

It’s an interesting thing going on in that essay, which is a wonderful essay about Abraham sacrificing Isaac. It’s that it also has some small parts about breastfeeding in between, which is incredibly strange, and I’ve been thinking a lot about that. What is that?

But it’s moving away from something. It’s going from a mother into society, and the leap of religion is going from a society into the unknown, into the things we don’t really know about, the things we don’t have language for.

There is another very interesting Norwegian poet — no, not Norwegian, but Nordic poet — called Inger Christensen. She wrote a collection of essays which is really brilliant, and she talks about those kind of border areas. It’s a matter of language — what we can express and what we not can express. In science, those are the string theories. That’s the things we don’t know. That’s the unknown.

And the border is the language. We don’t have language for it. We can’t really. She also said that — like a letter in a book cannot read what’s around it, cannot read the book — we are the same in the world. We cannot read the world. We’re part of it.

But that was Kierkegaard. Yeah, I find it hard to connect Kierkegaard in regard of children, sacrifice of children. And Bergman? Bergman is completely different somehow.

COWEN: But children are abandoned, both in his life and in the movies.

KNAUSGÅRD: I know. Bergman’s workbooks just came out in Sweden. It’s not his diaries, and it’s not his plays, but it’s kind of an in-between state, all notes he took when he was working with things. And it’s incredibly interesting because you can see how a film surfaced from almost nothing and just became a film. And you see all his struggles, and you see all of that.

But then in one particular passage, he wrote about a film he wanted to make, and then he said, “Today, my grandchild died.” And that was it. Just a little passage, like he really didn’t care. In a normal person, it would have filled that person completely. And then that little episode turns up in his next film, that the child is drowning.

There is another episode from Bergman’s life, that when his son was lying on his deathbed, he refused to have his father come there, and that’s a very, very strong statement.

COWEN: Sure.

KNAUSGÅRD: You have this almost archetypical artist putting his art before his children, before his family, before everything. You have also Doris Lessing who did the same — abandoned her children to move to London to write.

I’ve been kind of confronted with that as a writer, and I think everyone does because writing is so time consuming and so demanding. When I got children, I had this idea that writing was a solitary thing. I could go out to small islands in the sea. I could go to lighthouses, live there, try to write in complete . . . be completely solitary and alone. When I got children, that was an obstruction for my writing, I thought.

But it wasn’t. It was the other way around. I’ve never written as much as I have after I got the children, after I started to write at home, after I kind of established writing in the middle of life. It was crawling with life everywhere. And what happened was that writing became less important. It became less precious. It became more ordinary. It became less religious or less sacred.

I’ve never written as much as I have after I got the children, after I started to write at home, after I kind of established writing in the middle of life. It was crawling with life everywhere. And what happened was that writing became less important. It became less precious. It became more ordinary. It became less religious or less sacred.

It became something ordinary, and that was incredibly important for me because that was eventually where I wanted to go — into the ordinary and mundane, even, and try to connect to what was going on in life. Life isn’t sacred. Life isn’t uplifted. It is ordinary and boring and all the things, we know.

You have these myths, and they work for some. They don’t work for some, but you can relate to them. I have a friend. He’s a brilliant writer, and he always says, “Yeah. When you want to create something, you have certain . . .” I don’t know the English word. You have certain things that’s fixated. What do you call them? Premises? Or —

COWEN: Assumptions? Axioms?

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah, you just have to accept them and work inside of them. That’s the only way. If you can’t write, then you have to start right out from that fact.

I think that’s the best advice I ever got — to accept everything that happens. So if you have many children, it’s a good thing. If you don’t have children, it’s a good thing. You have to embrace it because that’s your life. That’s where you are, and writing should be connected to that — or painting or whatever it is.

COWEN: Your focus on Nazi history in part of book six of My Struggle — is that a kind of confessional for Norway and Knut Hamsun? Or the parts of Norway that were attracted to Nazism? How is that connected to the fact that you wrote a confessional about your own life?

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah.

COWEN: Since clearly you have no sympathies for a Nazi regime at all, but there’s a connection between your culture, history?

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah. It’s many connections. One would be that when my grandmother died, we found Mein Kampf in the chest in the living room. What was that book doing there? Had they read it? And I realized it was kind of a common thing to have that book. It was kind of a common thing to cooperate with the Nazi regime.

When I grew up in Norway, the story we were told at school was the heroic one: the resistance and how every able civilian resisted. But the fact is that Norway was . . . The wheels were rolling, and the society was working, and there had to be a lot of cooperation with the Nazis.

My other grandfather — he befriended an Austrian officer that was posted by where he lived. When I grew up, there was remnants from the war, like bunkers we were playing at. And it was like war was, in one sense, incredibly distant, but when I start to think about it, incredibly close. It was my grandparents’, parents’ world, really.

But that wasn’t the reason why I started to write. The reason was coincidental, basically, because I called my book My Struggle, which is the English translation of Mein Kampf, and then I had to read it. And then I realized Hitler’s book is his writing about his own self. I’m writing about my own self. It’s the same title.

I started to read him, and I got incredibly intrigued by what I read because there was so much — not that he was lying, but it was so much that was unsaid, so much that he twisted his life into something completely different. Couldn’t be true. And I just dived into that and started to read more about it and try to find out what kind of man he was and how all this could happen.

Well, it started out like it started in the book. It’s a reflection about names because I couldn’t use my father’s name in the book. My family forbid me that. So I started to be interested in and look around — what names really are, what they signify. Then I stumbled across a Romanian poet who wrote in German, called Paul Celan. His parents died in the Holocaust, and he was Jewish. He wrote postwar in the language of the Nazis.

COWEN: Best poet of the 20th century, perhaps.

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah.

COWEN: Yeah.

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah. And the rest is —

COWEN: Maybe Rilke.

KNAUSGÅRD: No, I think Paul Celan . . . Yeah, maybe.

But anyway, he wrote this incredibly, incredibly, incredibly intriguing poem where almost nothing can be named. There’s no names. And it’s like it’s almost impossible to say anything. It’s like the language is completely, completely broken, so there’s no connection between the element and the language. And I read that, and I wrote about it, and I realized this is — and it’s about Holocaust, of course — this is the end of what was started with My Struggle (Hitler’s).

And then that was the moment in the book . . . because Hitler also wrote in German, and he also wrote . . . You could read it. It’s bad. You can say whatever you want, but the fact that you could actually read him is intriguing. And you can see everything he wants to do is in the book.

So I wanted to describe that path from Hitler to Celan. It’s the only part in the book that’s not about me. But it is, of course, about me. And it’s the only part that’s not about our time. It’s about the past. It’s kind of a place, kind of a dark mirror in the book where you could see everything be . . . get a perspective to everything.

And it’s the only part I found really pleasure in writing because there was so much I discovered during writing. That, and it wasn’t about me, which is a burden to do, but that was different. It’s about the generation that grew up with the First World War and made the Second World War happen.

COWEN: So many great Norwegian writers — Ibsen, Sigrid Undset, Knut Hamsun — there’s nationalism in their work. Yet today, liberals tend to think of nationalism as an unspeakable evil of sorts. How do we square this with the evolution of Norwegian writing?

And if one thinks of your own career, arguably it’s your extreme popularity in Norway at first that drove your later fame. What’s the connection of your own work to Norwegian nationalism? Are you the first non-nationalist great Norwegian writer? Is that plausible? Or is there some deeper connection?

KNAUSGÅRD: I think so much writing is done out of a feeling of not belonging. If you read Knut Hamsun, he was a Nazi. I mean, he was a full-blooded Nazi. We have to be honest about that.

COWEN: His best book might be his Nazi book, right? He wrote it when he was what, 90?

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah.

COWEN: On Overgrown Paths?

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah.

COWEN: To me, it’s much more interesting than the novels, which are a kind of artifice that hasn’t aged so well.

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah.

COWEN: But you read On Overgrown Paths, you feel like you’re there. It’s about self-deception.

KNAUSGÅRD: It’s true, it’s a wonderful book. But I think Hamsun’s theme, his subject, is rootlessness. In a very rooted society, in a rural society, in a family-orientated society like Norway has been — a small society — he was a very rootless, very urban writer.

He went to America, and he hated America, but he was America. He had that in him. He was there in the late 19th century, and he wrote a book about it, which is a terrible book, but still, he was there, and he had that modernity in him.

He never wrote about his parents. Never wrote about where he came from. All his characters just appear, and then something happens with them, but there’s no past. I found that incredibly intriguing just because he became the Nazi. He became the farmer. He became the one who sang the song about the growth. What do you call it? Markens Grøde.

COWEN: Growth of the Soil.

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah. Exactly. It’s like he’s fistfighting himself, doing that. So he’s not your nationalist. He’s incredibly complex, and the interesting thing is that you can see that struggle in his writing.

COWEN: Is your own American travelogue a revision of Knut Hamsun’s in some way? Like, “Well, Norway’s going to get it right this time”?

KNAUSGÅRD: [laughs] No, but actually, I have thought about doing that — go in his footsteps because he was there for quite a long time. He drove a tram in Chicago, did a lot of things, and it’s an exciting story, really.

But anyway, the thing with writing in his case is that he’s getting so close to the world and to the people in his writing. It’s so complex that he is not a Nazi in his writing. But in his essays and in his speeches, there’s a big dissonance. There, he’s a Nazi.

And that’s what a teacher can do, is to get you so close to these things that nationalism just disappears because they don’t exist on that particular level. You have to move away from the world — to be able to establish a distance — to be able to talk about these things at all. Norway is a nationalistic country, but it’s not in any bad way at all, really. It’s a very innocent country.

COWEN: What’s the worst thing about living here in London?

KNAUSGÅRD: The worst thing?

COWEN: The worst thing.

KNAUSGÅRD: I think it’s — to me, being an outsider, it’s both the worst and the most interesting, and that’s the huge difference between the classes. It’s the extreme poverty, and then you just walk up a hill and it’s incredibly rich.

It’s not only a matter of classes, but the area I live in is a rather poor area. It’s a black area. And then you go up the hill and it’s a white area. I think it’s a kind of hopelessness, really, to be here because you can’t do anything about it. It’s in the structure in the society.

But then also, it makes it incredibly — the variation incredible and the richness incredible, and so it’s very much an alive city. Coming from Norway, it’s very different. It’s like all kind of things going on simultaneously, which is incredibly interesting and nice to at least — I know I’m not a part of it — but to see and to be around.

But it has that backside with the privilege being . . . going around and around and around and around in the same kind of class and the privilege the same; you can’t move from one to another. The Scandinavian society is much more egalitarian in that sense.

COWEN: As you well know, Hans Jaeger was a seminal influence on Edvard Munch, and you can think of him as a highly intellectual, cynical nihilist. Munch knew him in his early years. Has there been a Hans Jaeger figure in your life who’s a formative influence? It doesn’t come through in your books.

KNAUSGÅRD: You mean personally or through reading?

COWEN: Personally. Who’s your Hans Jaeger?

KNAUSGÅRD: [laughs] I don’t have a Hans Jaeger, but I have this writer I really admire, and he’s really something.

COWEN: Who’s that?

KNAUSGÅRD: He’s called Thure Erik Lund. He’s not translated into English. He’s very wild — wild as a person, wild as a writer. He has inspired me a lot and showed me what’s possible to do in writing. But he’s so particularly that it’s hard to translate him. If it had been written in English, he would have been, I guess, level of Thomas Pynchon or whoever. He’s that good. But he’s so idiosyncratic that it’s hard to translate him. He’s not my Hans Jaeger, but he’s an influence.

COWEN: Edvard Munch — he was known for beating his paintings, abusing them, not treating them very well.

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah.

COWEN: Have you ever done the same with your books?

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah, I’m kind of a careless person. I don’t take backups, and I have window open — it’s raining on my computer. I have lost a computer down on the tracks of trains, and I have lost them, you know, but it always turns out well.

But that’s not the same. I don’t care about how a book looks. I don’t deal with that part of it at all. When I’m done with a book, there’s hardly no editing. I just leave it and publish it, and I want to move on because it’s the process of doing it that interests me, not the result. I really hate it when a book is done because then I know it’ll take a few years before I will get into something else.

In that I can recognize Munch. He hardly finished a painting in his life. And he was very reckless with his paintings. It is a certain aesthetic in that as well.

It’s like in writing. It’s like the difference between Dostoevsky and Tolstoy. Dostoevsky really didn’t care. He just didn’t have to describe it fully. Just a few sentences, done with that, and go on and go on and go on, looking for something, like a flame or something burning or something, the intensity of something he was looking for.

Tolstoy — he wrote about everything and painted it fully and did so wonderfully, but it is completely different aesthetics, and they reach completely different places. When I was young, I thought Dostoevsky was the primary, the one that had reached the front. Now, I’m older, it’s Tolstoy, really.

COWEN: Edvard Munch — he stuck with Dostoevsky as an influence.

KNAUSGÅRD: Very much so. The day he died, in the afternoon the day he died, he read Dostoevsky, and then he died. So he just followed him throughout his life. I think Dostoevsky was part of forming his identity as a painter — exactly what’s unfinished, exactly what’s raw.

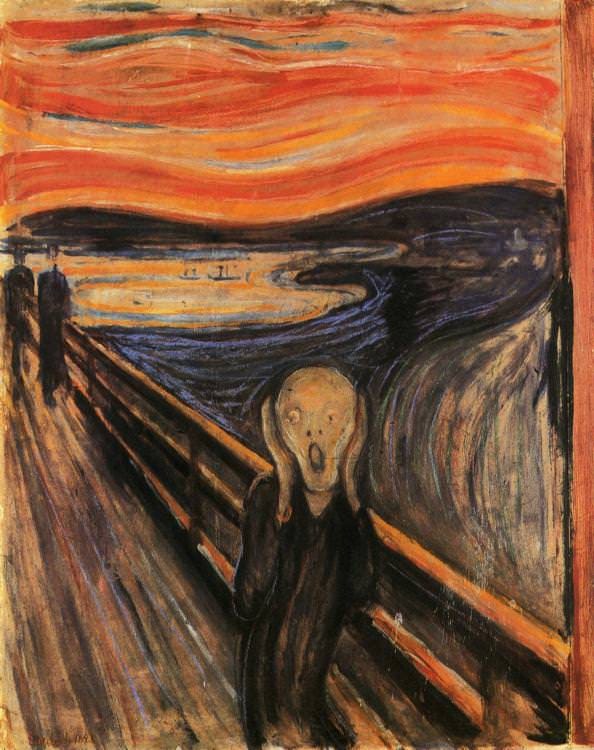

COWEN: Is The Scream a self-portrait of Munch? And is he wearing a mask or a death mask?

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah. The Scream is based upon an experience he had walking up the hill outside of Oslo, seeing what you see in that painting, hearing the nature scream. So in a way, it’s a self-biographical painting, but the radicality of that painting — it’s hard to get a grip on now, I think. We are very much used to that kind of distorted ways of depicting the world.

That’s a long story about . . . I write a lot about it in the book because it was fun, because that’s a painting that everyone knows, and everybody has a thought about it. I tried to write about it afresh. What is this? What did it do? I can talk about it if you like, but it’s a long, complicated story. I don’t know if I can do it.

COWEN: Let me ask you about Between the Clock and the Bed. Jasper Johns’s paintings are often mysterious, but he chose to redo Between the Clock and the Bed. What is Johns on about? What is Munch on about in that painting?

KNAUSGÅRD: I don’t know about the Jasper Johns. Using the pattern on the bed, isn’t he?

COWEN: Right, yes.

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah. Munch made some remarkable self-portraits, I think. He did so throughout his life. He started at 18–19, and they were all very different, and I think they were all very good. I think this is one of the very last ones.

The thing with this is, it’s so incredibly simple. It’s just a man standing there, and it’s like he’s showing us that. This is it. There’s no posing. There’s no defense, and Munch was a man full of defense. I think painting was a way for him to get under the defense and reconnect with the world. In this painting, that’s what it does. It’s like the guard is down. This is what it is.

COWEN: Is autobiography a kind of defense or protective strategy for you, a way in which life cannot be a disappointment? There’s always something happening you can write about. In that sense, your portfolio, so to speak, is very diversified.

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah, it is a place to hide. That it is, I mean, that’s obvious. There’s that wonderful sentence in Witold Gombrowicz, Polish writer. His diaries are, I think, amongst the masterpieces of the last century. It really is brilliant. He published his own diaries when he was alive. When they were published, he said, “You know, I just have to retreat one step inside myself.”

That’s what you do when you reveal so much about yourself. It’s like you could just take a step back, and it’s all right. It’s not even connected to you if you do that. It’s like, “Okay. I never think about what people know about me.” The act of writing is, for me, a place I can go to and where I am protected somehow.

Publishing books is a different thing, of course. I try to disconnect from that. Don’t think about it — the publication of it. What I want to do is to be in the space where I’m writing. It’s also a way for me to understand what’s going on, to see things that I normally don’t see because I’m very much enclosed in myself and in my own space, and I don’t really notice things, and I’m kind of closed off to the world. So writing is a way of opening up, also.

Publishing books is a different thing, of course. I try to disconnect from that. Don’t think about it — the publication of it. What I want to do is to be in the space where I’m writing. It’s also a way for me to understand what’s going on, to see things that I normally don’t see because I’m very much enclosed in myself and in my own space, and I don’t really notice things, and I’m kind of closed off to the world. So writing is a way of opening up, also.

There’s a lot of things, but I’ve been writing for so long now that it feels like a place I can go to. Go into that place and sit down, and I will be at peace as long as I am there. Even though I write about terrible and heartbreaking things, it still is a place of peace.

I do find reading the same thing. I’ve always done that. I think that was why I read so much when I was little and when I grew up. I think I became a writer the moment I realized that that space is the same. The reading space and the writing space are basically the same, and you do the same things there in those spaces.

COWEN: Why does Munch have so many mediocre paintings, some might even say bad paintings?

KNAUSGÅRD: He didn’t really care, I think. He wanted to capture something, and if he didn’t do that at the first instant, he moved on. But he kept all the bad paintings, too. I find that also very interesting. [laughs]

COWEN: Is that a model to emulate or a cautionary tale for you?

KNAUSGÅRD: I was curating a Munch exhibition in Oslo at the Munch Museum, so they gave me access to the magazine in the basement. I was shocked because it was . . . You know, you pull out these enormous kind of walls, and it was maybe 10 paintings or 5 paintings or 7 paintings or 15 paintings on them. And it was a complete mix-up, with masterpieces, terrible paintings, sketches, mediocre things, old things, new things.

It was like being in a work of progress. If you go to museums, you see everything finished. Everything is almost stylish. Then it’s everything is art. This was completely different. This was entering into a process because the paintings they have are the paintings Munch had when he died, everything he kept, everything he didn’t sell.

When I did that exhibition, I thought that was an opportunity to try because . . . In Norway, at least, you can’t really see Munch because you’ve seen it. He’s so big, and you see all the paintings so many times that you can’t really experience them. So I tried to use other paintings to give a new access to Munch, what he was doing. Amongst them were sort of bad paintings.

COWEN: You’ve bought a Munch, right? Head of a Woman?

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah, yeah.

COWEN: Why buy only one? Why not buy a second? What is your thinking on the matter?

KNAUSGÅRD: It’s expensive.

COWEN: You enjoy it, right?

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah, yeah. It was expensive.

COWEN: They’re capital assets. You can resell it someday. Your heirs will have real value.

KNAUSGÅRD: No, no. It was hard for me to buy that one. Having a Munch in Norway is very bourgeois, and you’re very settled when you do that. My excuse was that I got a fee for the curation of the exhibition, and I thought I could use the fee for buying a Munch, so that’s what I got.

It’s just a drawing. It’s nothing, really, but it’s incredibly nice. To see anything with a good work of art is that you can see it every day, and you don’t get tired. It’s like it gives endlessly. It’s very simple, extremely simple, but it still comes something from it every day, actually, which is what you want from a piece of art.

COWEN: You showed up seven minutes early for this interview. Do you think of yourself as ultimately a defender or a critic of bourgeois culture and bourgeois virtue?

KNAUSGÅRD: When I was a teenager, I was very much in opposition to it then.

COWEN: But that’s the typical pattern of someone who’s older, right?

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah, but you know, I don’t really care. That’s true. I’m too busy raising children. I’m too busy trying to survive that I can’t really afford to think in those terms. I remember when I got my first daughter, and I was full time with her. I thought, “This is very unmasculine, and this is taking away my identity.”

But then I had three children and then four children, and who cares? You just deal with them and try to be good and go on. It’s the same now. It’s about that. If that’s bourgeois, if that’s what it is, I don’t care.

COWEN: You’ve written in great detail about raising your children, but looking back, what is it you feel you understand now that you didn’t then? If you were to add in a footnote? Because retrospective memory is quite different from experience in the moment.

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah. That’s hard. I mean, there are so many things I did that I wish I hadn’t done. But that’s life.

COWEN: Most of them don’t matter, right?

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah, yeah, but that’s life. That’s how it is, and you can’t undo it. You do have to experience things and learn things. I can’t tell a young father what to do, what to not do. You have to find out yourself.

The thing about the book, which I’m happy about, is that it covers the process. I wasn’t aware of that, really, but a very short period of time, really. I wrote it in two years. As you say, I’ve forgotten everything now in my head, but it’s in the book. It’s captured in the book — to see how I was thinking, to see, yeah, mistakes I did or not did or whatever. But still, it’s like a slice of life that’s in those books.

COWEN: Is it possible at all to enjoy your works on audiobook, or is the use of voices different from yours too discordant for stories that are so personal, that are so you, so confessional?

KNAUSGÅRD: No, I don’t read my books and I don’t listen to them. In Germany, they have readings very different from here. It’s readings, so you have an interview with the writer for maybe five minutes, and then it’s one hour of reading. When it’s a foreign writer, they have actors reading. There have been some incredibly nice experiences if there is a good actor reading. It’s like he makes the book into . . . has nothing to do with me —

COWEN: Is it better than you?

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah, yeah, yeah. But then it becomes proper storytelling, and it becomes literature, and that’s very strange to witness, but also very nice.

COWEN: You’re obviously very fluent in English. What do you feel the English-language reader loses in the translation from the Norwegian?

KNAUSGÅRD: I think the translations are excellent. Donald Bartlett — he translated five and a half of the six books, and Martin Atkins did the last part of book six.

He asked me in the beginning how hands-on I wanted to be in translation, and I said, “You can do whatever you want to. I don’t want to have anything to do with it.” Then I remember getting book five in the mail, and almost accidentally, I started to read, and I just kept on reading because it was so well done. It was in English, so it was kind of removed from me, but still I recognized everything, and I think he’s a world-class translator, Donald Bartlett.

But an interesting thing in that regard is that I have another translator for my other books. She’s a poet. She’s half Norwegian, half American, called Ingvild Burkey, and she translates my language completely different. It’s a completely different feeling of her language than his language.

Both are brilliant but in very different ways. He’s much more translated it into an English novel, and she’s much more translating into a Norwegian-feeling English. So she’s much more close to my language, and he’s much more above, and both come from the same writing. Very different, both very good. They have different qualities, so to speak.

COWEN: Why do we put dead bodies in the basement rather than the attic?

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah, good question.

[laughter]

COWEN: You asked it yourself in book one.

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah, but that was a long time ago.

COWEN: To pursue your father’s question, how many people in solo car accidents are actually suicides?

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah, exactly.

COWEN: Are all Swedes crazy?

KNAUSGÅRD: Not all.

COWEN: Not all?

KNAUSGÅRD: No.

COWEN: Which Ingmar Bergman film has influenced you the most and why?

KNAUSGÅRD: Sitting here with you, I can’t really think of any Ingmar Bergman film.

COWEN: You once said Wild Strawberries was your favorite, but favorite may not be the same as influence.

KNAUSGÅRD: No. I think Scenes from a Marriage is incredibly good, to be serious.

COWEN: That’s the best movie ever made if you watch the whole thing through, I think.

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah, yeah. I think that’s his richest and best. Yeah, I think so. I love Persona, and I do actually — even though I know Lars von Trier hates it, I do like Fanny and Alexander also. It’s such a fairy tale touch to it, which I like. But no, it is Scenes from a Marriage, I think.

COWEN: I like Smiles of a Summer Night very much, the Mozartian feel, the Shakespeare connection. It’s a very alive movie for me.

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah. Yeah.

COWEN: Peter Handke — what kind of influence have his novels had on you?

KNAUSGÅRD: That’s a hard . . . I’m discussing him and his influence in book six, actually, because he is a writer I absolutely admire, and I think my writing doesn’t reach up to his knees, [laughs] his writing’s knees. But My Year in the No-Man’s Bay is a book that I read — must have been in the ’90s when it came out — before being a writer myself. Or was it exactly that moment I started to be a writer, I think. That was very influential.

And his writing about the things that don’t belong in a story and the things that really don’t belong in a landscape — the areas between the city and outside of the city — the railway tracks, the grass, the fences, kind of the world as it is outside of the story, I think. He’s just . . . I don’t know, and the book about his mother is absolutely fantastic, I think.

COWEN: Is Elena Ferrante the main contender for having bested your achievement? For handing out lifetime achievement awards for contemporary serious fiction.

KNAUSGÅRD: I’ve only read one Ferrante book, and that was Days of Abandonment. I would have cut off my left arm to write that book. I think it was so absolutely brilliant.

COWEN: Try The Neapolitan.

KNAUSGÅRD: I know, I know, I know, I know. As I say, I have problem with things I know is very good, to enter it, because I’m not a jealous type, but I feel I will in the end. But that book, Days of Abandonment, was really, really outstanding, good.

Luckily, there’s no competition here, so there’s nothing to . . . I do what I can do. You have incredibly good writers everywhere, in every country, and when I’m outside of a novel, I just look at them, and I think it feels so hopeless. How are they doing this? How are they managing to do this? And if you think like that, you can’t really write. It has to come, has to be personal, has to come from inside, has to be within something without looking out.

You have incredibly good writers everywhere, in every country, and when I’m outside of a novel, I just look at them, and I think it feels so hopeless. How are they doing this? How are they managing to do this? And if you think like that, you can’t really write. It has to come, has to be personal, has to come from inside, has to be within something without looking out.

What you’re talking about is outside of books. Then you can start and be jealous and, “Oh, no.” Or, “Why did he get that grant and I not?” And “Why did I get so bad reviews?” And stuff. That’s worthless. It’s completely worthless, and I try to stay away from it as much as I can.

COWEN: But we know Ibsen was obsessed with medals and honors, right?

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah, he was.

COWEN: Was that a character flaw?

KNAUSGÅRD: It’s very funny, a very funny flaw, I think.

COWEN: One you share or not?

KNAUSGÅRD: I don’t share that, no. But he had also a mirror in his hat so he could take out his hat and look at himself, which is also very funny. And he was a very little, very little man, loving medals and having a mirror in his hat. That’s funny.

COWEN: From another literary tradition, take Calvino, Borges, Cortázar. Are they, in your view, in some ways overrated, and is your objection to them ultimately a political one?

KNAUSGÅRD: No.

COWEN: They’re running away from life in a way. Correct?

KNAUSGÅRD: No, no. I feel quite comfortable in Borges. I think he’s superior. I think he’s a master, really a master, and an author I’ve learned a lot from, not in ways of telling a story, but what the story tells you about the world. He has been very influential in my worldview, basically, especially one called “Tlön, Uqbar.” It’s a short story.

COWEN: Sure.

KNAUSGÅRD: It’s just the best short story ever written, I think.

COWEN: We agree on that, actually.

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah. Calvino is less . . . Calvino had . . . yeah. Cortázar is also very good, but he’s not Borges, I think. And Calvino, I love. The Baron in the Trees — what it’s called — is one of my favorite books.

If I could write like them, I would, but I can’t. Every time I have something fantastic, I mean in that sense, something that really could happen, I try to write it. I can’t make it work. Just don’t have it in me. Has to be some sort of realism. I have to believe in it myself. And the magic with Borges is that you believe it completely. He makes it completely believable.

And his essays are absolutely wonderful. And in every little essay, every short story almost, you can pull something out of value. So he’s absolutely one of my favorites.

COWEN: Is Magnus Carlsen going to withdraw from the World Chess Championship cycle?

KNAUSGÅRD: Chess is not my world.

COWEN: Has liberalism exhausted itself?

KNAUSGÅRD: Maybe not liberalism, maybe capitalism.

COWEN: There’s something about the aesthetic people in the early 20th century — Hamsun included — seemed to think that a vital sense of the aesthetic — maybe it didn’t quite have to be fascist, but it had to move the artist somewhat in a direction which we, today, would mostly consider unpleasant. Do you think a strong notion of the aesthetic and liberalism are totally compatible?

KNAUSGÅRD: Good question.

COWEN: T. S. Eliot would be another example of someone who moved in a quite unsavory direction.

KNAUSGÅRD: I don’t know, really. I wonder if fascist literature — if that’s even possible? It’s like those two concepts are not able to —

COWEN: But liberalism in literature is also tricky. Take Romain Rolland, who is a great classical liberal. He wrote books that everyone read at the time, but they’re mostly forgotten. They’re seen as a little flat.

KNAUSGÅRD: I don’t know, what do you mean by liberalism in this?

COWEN: The notion of a particular neutrality across values, which government then enforces by having impartial laws, and people believe strongly in some underlying notion of neutrality. Doesn’t that clash with the aesthetic impulse at some level?

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah, of course. Yeah, if that’s what you meant. Yeah, definitely.

COWEN: In your own thought, how do you reconcile those two things?

KNAUSGÅRD: What I’m struggling for in my writing is what I call literary freedom, and it’s a space where I can be free in every sense, where I can say whatever, go wherever I want to. And for me, literature is almost the only place you could think that that is a possibility.

What I’m struggling for in my writing is what I call literary freedom, and it’s a space where I can be free in every sense, where I can say whatever, go wherever I want to. And for me, literature is almost the only place you could think that that is a possibility.

My fear is that that space has come closing down on you. You’re closing it down yourself and becoming more afraid for what you’re saying. “Can I say this? Can I do this?” And this power is also strong, you know? It’s so hard to go somewhere you know this is wrong, or this is . . .

I did it with My Struggle because I wrote about my family, and I knew, of course, I shouldn’t do this, and really it is immoral to do this. And then I did it because I wanted to say what I wanted to say, and I wanted to be free to talk about, to write about my own life in a complete and in a free way.

That’s also why I admire writers like Peter Handke. He had the Yugoslavia controversy around him, and you have a lot of controversies around him. But what he does is, he’s there. He’s hardcore, saying what he thinks and stands for it, no matter how ugly it looks from the outside. And that’s what you can do in literature and no other place, I think.

This is an internal struggle in every writer, I think. And it goes in almost all levels of society. I find it hardest to go into the private places that belong to my family and my life, but you have all the political topics. You have a lot of things you can think of. But it’s good that it’s a struggle, and it’s good that there’s an arena where we can have these fights.

But the notion that literature should be good in a moral sense — that I find ridiculous. That’s useless.

COWEN: As a boy, which were your favorite comic books? You’ve written that you loved comic books growing up.

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah. When I was little, it was Lee Falk’s Phantom. That was really big in Norway. A bit older, it was Modesty Blaise. But I read absolutely everything.

COWEN: And what are the politics of those comic books that young boys tend to read?

KNAUSGÅRD: Then, in the ’70s, it was very sexist, very racist, and all kinds of things. My mother discovered what I actually was reading, so she forbid me to read comics, which was a very harsh punishment, it felt at that time. But it made me start to read books. So it was a good thing in the end. She was completely shocked by what I was reading, and it was common. But that was the ’70s. I think it has changed, maybe. I don’t know.

COWEN: You’ve spent some time in a creative writing program — is that correct?

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah.

COWEN: Did you learn much there, or was it just a waste of your time?

KNAUSGÅRD: I learned a lot. But what can I say? It was like running into a wall. I was running full speed into a wall, and I fell down, and I lay down. For six, seven years I couldn’t write after that. I was young when I started. I had all this illusion about myself and about literature and what I could do, and I couldn’t do anything. I felt like they were ridiculing me, and they were, actually. Then it took many years, and then I could write.

And what I learned — I met the world literature.

COWEN: Yes.

KNAUSGÅRD: And I met also a writer that is, yes, he is Norway’s best writer. He is called Jon Fosse, and he was 29 at the time, and he was a teacher there. His notion of quality is absolute, and he was very, very important to me just because he showed me where the level should be. I haven’t reached that level, but I’m above where I was when I was 20, at least. And it was very good to know that. “This is literature; this is what literature can do.”

But it was completely terrible for me at the time and many years afterwards because I had no self-confidence. They took away all my self-confidence. I couldn’t write.

COWEN: The creative writing program took away your self-confidence?

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah, yeah.

COWEN: And that was a good thing?

KNAUSGÅRD: In the end, it was a very good thing.

COWEN: How did you get your self-confidence back?

KNAUSGÅRD: I haven’t got it back.

COWEN: Haven’t got it back?

KNAUSGÅRD: No, but I have helpers to help me. They want to pick me up from nothing, and my assistant editor — I really couldn’t write when he saw something I’d written and believed in me. He still believes in me, and he has to tell me that — every week — what I’m doing is interesting, what I’m doing is good, and that he believes in me. And he has done so for 20 years. Without him, I wouldn’t have been a writer.

I also have friends who do the same thing. They said, “Okay, this is good. Don’t give up. Keep on writing.” And they did because if not, I wouldn’t have the strength to do it. Maybe I would, but it makes my writing life much easier to have helpers.

COWEN: Your first book in English but, I think, your second book overall: A Time for Everything. Why did you write a whole book about angels?

KNAUSGÅRD: I really don’t know. I’ve always been interested in the physicality of man, matter, the brain itself, the physicality of the brain, the way we are animals, the way we eat, and the way we take the world in, and the primitiveness of us. And then, you know, the heaven above, all the things we dream of.

When I read the Bible, something that occurred to me was the physicality of the angels. That’s such a wonderful image. And I thought, “Okay, they were eating in the Bible, they are walking with God in the Bible.”

I thought, “What if I read the Bible from that perspective? What happened to the angels? Where are they?” Because they saw angels before. We don’t see them. Then I thought, “Okay, maybe they have been tempted to be in the physical world too much, and then kind of been almost centrifuged into the world and been part of the world and can’t escape, and they’re still here around us.”

That was the thought. And in a way, it’s a metaphor for what happened with religion, why we’re not . . . many of us don’t believe anymore. Why there’s no heaven above us except commercials and TV programs and stuff. What happened? What happened with religion? What happened with God? What happened with heavens? You know? How come we are all down here now, and what’s that about?

That was not why I wrote it, but that was the outcome of the writing.

COWEN: And why the fascination with the Cain and Abel story? Right? It’s family struggle, and it’s rivalry.

KNAUSGÅRD: Yeah, that’s true. And it’s only like eight lines or something in the Bible. It’s almost nothing. It’s so rich, and it’s like it’s bottomless. They have been discussing that and reading that for thousands of years, and you can still say something new about it. That simple story — a brother killing another brother.

I’m just reading about gnosticism now. They take a liking — some of them — for Cain. They like to turn everything upside down. So God is really the devil, and this really is hell, and Cain is really the good one, the one to look at. You know, it’s just an endlessly fascinating thing. It means so much — so many layers of meaning in that simple, simple story.

That’s the best part of the Bible: those very short stories. Incredibly rich and layered with meaning.

COWEN: To close, why don’t we return to your new book? Again, it’s called So Much Longing in So Little Space. Give us your take on Munch, The Scream. You’ve referred to this earlier.

KNAUSGÅRD: My take on The Scream? You know, that’s what happens when you’re writing. You just start. I just sat down with a Munch book and thought, “Okay, I’ll write a book about Munch. Let’s see where this goes.” Then you just enter it, and then comes something back, and then, two months later, you have a book.

The Scream is one of the most iconic paintings there is. Everyone, I think, has seen it. It’s so recognizable. And almost we have an intimate knowledge of it. We see it, you know? But the painting is about the opposite. It’s about something very strange. It’s hard to do this in English, but it’s about the world being almost unrecognizable. It’s seeing how strange the world is. And we do this in that painting that we instantly recognize.

And it’s a painting about anxiety, and anxiety is incredibly painful. So, it is a painting about pain. But we see a million dollars, we see its fame. We don’t see that.

But the interesting thing for me when I wrote about it was what kind of paintings Munch had access to and how they painted at that time. Because no matter how painful things were, they were always taking place in a space, in a room. And having that space, having that room, you know the events in that room will one day be over. Something new will take place there.

If Madame Bovary is very painful — the ending — but you know that world will continue. And there is a kind of a comfort in that. There isn’t an acuteness in it. You could see it. You know it will pass. And you observe it from the outside, so you see it at a distance. You see something painful — a sick girl — at a distance, and it’s in another room, and it will pass. There is a comfort in that.

But Munch does set in that painting to remove that room, to remove that space. Because all the landscape is subdued to the person in the painting. So it’s his landscapes. There’s no room in it; there’s no neutrality. When that person is gone, the landscape is gone.

So, there is no space, and there is no time. It’s instantly painting, it’s acute. It’s like it’s happening now, and we share the space with the painting. And in that is the radicality of the painting — that there’s no space and there’s no comfort. It’s an acute thing. It’s instant, and you have to relate to it. You can’t see that painting without relating to it. I mean when you saw it for the first time.

And the interesting thing now, I think, is that that’s a fair description of the world — how it is now. It is an instant world. We get access to painful things that happens when it happens. Today, there was a massacre in New Zealand. The minute it happens, we know about it, we relate to it, we feel the pain, and we see the pictures. That didn’t just happen. That didn’t happen at Munch’s time. It was unheard of.

Now that’s the world. We live in the world of Scream. There’s no space between us and the world. Everything comes bombarding us, you know?

So, what art has to do now is the opposite. It has to create space. It has to recreate rooms. And I was thinking about that and also writing in the book about — I was at an exhibition of Anselm Kiefer here in London. It was the White Cube. It was absolutely magnificent, but there was no people in it; it was only spaces, only room. And it was kind of mythological rooms. It was like it was giving space to events that wasn’t even there, back somehow.

I think both Kiefer and Munch are great artists, but they live in different times and they had different missions. For Munch, it was very important to give access directly to pain and to distorted vision of the world, and to give a more true account of how it is to be, I think he wanted to do.

And now it’s the opposite because now we need space and we need comfort and we need time and we need something. I’m not sure if art is what should do that, but that’s what I felt when I started to write about Munch.

And another interesting thing is that exactly the same thing is going on in the literature at that time, you know? You have the epic novel with all the characters, all the rooms. Tolstoy is a very good example because that is a book about rooms.

And then you have, for instance, Knut Hamsun in Hunger, which is just one person and his distorted version of the world that exists. And when he dies, the world disappears.

COWEN: Karl, thank you very much for coming by.

KNAUSGÅRD: Thank you.