After winning the Nobel, Paul Krugman found himself at the “end of ambition,” with no more achievements left to unlock. That could be a depressing place, but Krugman avoids complacency by doing what he’s always done: following his curiosity and working intensely at whatever grabs him most strongly.

Tyler sat down with Krugman at his office in New York to discuss what’s grabbing him at the moment, including antitrust, Supreme Court term limits, the best ways to fight inequality, why he’s a YIMBY, inflation targets, congestion taxes, trade (both global and interstellar), his favorite living science fiction writer, immigration policy, how to write well for a smart audience, new directions for economic research, and more.

Watch the full conversation

Recorded September 25th, 2018

Read the full transcript

TYLER COWEN: Today I’m here with Paul Krugman, who needs no introduction. Just to remind you all, this is the conversation with Paul I want to have, not the one you want me to have.

To start with a very basic question: The major tech companies have become increasingly controversial. Do you think there’s a significant market failure there? And if so, what would it be?

PAUL KRUGMAN: It’s hard. I think that it’s hard even to start with the market failure. Everything about tech, certainly everything about networks, is a violation of the principles that say that a market should be efficient. The trouble is, it’s hard to sort out. It’s not that there’s any one thing.

It’s got increasing returns, it’s got imperfect competition, it’s got spillovers. So I’m not sure what I know is the particular market failure. There’s no reason at all to think that Facebook or Twitter or Google are doing the optimal thing from a social point of view. The trouble is, trying to figure out what to do as an alternative is not trivial.

COWEN: They have zero price. That’s very different from the monopolies of the past. They don’t restrict output. They try to build these platforms, and it seems increasingly clear, the plan is not to raise price someday, but just to make the platform as big as possible.

Is that problematic? Or is that just consumer paradise?

KRUGMAN: What’s problematic is that they’re still — although they’re not charging us anything — they’re not in business for our health, they’re in business for their health. They’re in business to sell something else. What Google is selling, really — it’s still ads. It’s selling advertiser access. At some level, that’s what Facebook is doing as well.

Since it’s indirect, in some ways, the reasons to think that it’s going to be non-optimal are even greater. You can see a little bit. I actually don’t use Facebook. I have an account, which is impossible to close, but I don’t use it.

I do use YouTube. I use it only for music, but I gather there’s a lot of politics on it. YouTube actually has algorithms that push you towards more extreme stuff. That’s because that enhances their ability to market their position.

It’s probably not what most people, if you ask, “Is this what you want?” would say they want. But YouTube isn’t interested in what you want — of course, it’s part of Google — but it’s interested in what it can use to make money.

This is nothing at all like an Econ 101 supply-and-demand market. There’s no reason at all to think it gets it right.

COWEN: The New York Times recently referred to a new movement. They called it “hipster antitrust.” The notion, for instance, that maybe Amazon was bad for a more general commercial ecosystem of publishing and retail. Do you have an opinion on hipster antitrust?

KRUGMAN: [sighs] We need something. I haven’t actually looked at the hipster antitrust. Two things, actually, I think are pretty clear. One is, the old antitrust paradigm still has a lot of relevance.

Most of the economy is still not, in fact, novel tech, zero-marginal-cost stuff. Most of it is still traditional stuff, and the fact that we largely stopped enforcing good old-fashioned antitrust is actually a problem. It is part of the problem with our economy and part of the problem with rising inequality. How big a part is something? That’s hard to pin down, but it’s something. Good old-fashioned antitrust is far from irrelevant.

Second, there’s a whole bunch of issues. The role of this handful of tech platform providers in possibly distorting markets is a pretty big deal.

I have to admit, I haven’t put a lot of effort into trying to think about what the solutions are because it just seems like the political climate for actually doing anything is probably not there. The chance of doing anything good is not high, but that may be a bad judgment on my part.

I’ve been more focused on other areas where the market failure is so pervasive that even a market failure framework is almost the wrong way to go about it, like healthcare.

On current politics

COWEN: You’ve been tweeting a good deal about politics lately, and in particular the notion that malevolent intentions may be stronger than you had thought. If you had to explain to someone — not using any names or even party names — but just in terms of a model, what has gone wrong for the United States lately?

How would you boil that down to its essence in terms of what you’ve called toy models?

KRUGMAN: Put it this way: our political system is set up on the basis that we elect representatives who will not exactly reflect their voters but will, in fact, deliberate and exercise independent judgment. But we are in an extreme partisan environment in which, for all practical purposes, only the party matters.

All that matters on most things is whether there’s an R or a D, which means that all of the . . . Not that long ago, people used to refer to the Senate as the world’s greatest deliberative body in a non-ironic fashion. [laughs]

These days, it’s ridiculous. There is no deliberation that goes on. It’s a completely partisan institution. If the president is of one party, and the Senate majority leader is of another party, presidential appointments just don’t even get hearings.

COWEN: What’s the structural reason why that’s become worse? As you said, it was once much better.

KRUGMAN: I think it’s two things. One is simply, I do believe that, in the end, there’s a pretty strong correlation between income inequality and partisan polarization. Political scientists who measure polarization have found that’s a really strong correlation. It makes sense.

In effect, the increasing weight to the right tail of the income distribution has dragged one party off in its direction. That’s opened up a large gap so that the center really just did not hold. There used to be at least some overlap on economic issues between the parties, and there is none now.

The other, which is uglier . . . One of the bases of some degree of bipartisan shift in our politics was, in fact, the overt racism. We used to have two dimensions in American politics, one of which was race — this is what the political science modelers tell us — one of which was race, the other of which was essentially left/right on economics.

Those have collapsed into a single dimension now. That means that you no longer have the populist Southern senator that used to provide part of what was, in bad ways, the political center. That’s another piece. I have to admit, when all is said and done, I find it a little bit mysterious.

It’s hard for me to quite understand. I can talk about it. I think that the role of money in politics has created . . . a lot of people in political life now have spent their entire lives within a partisan ecosystem, never really having to step outside. Any independence in judgment, any demonstration of an independent conscience is actually career destroying.

So the kind of people you get are people who are basically bad people, at the very least very cynical people. I still find it hard to understand how people can be quite as cynical as they have become.

COWEN: Hayek wrote a famous essay, “Why the Worst Get to the Top in Politics.” At the time, he seemed to think it was a fairly universal tendency, which maybe in the 1940s was a reasonable thing to believe. But there seems to be a lot of variation. What’s your underlying model for why the worst sometimes do or do not get to the top?

KRUGMAN: I think there was a time — think about being a US senator — there was a time when, I think, voters cared about someone who wanted to be a US senator seeming senatorial, seeming to have some gravity, some strength of character. Now, often that may have been an illusion, but there was still some sense that you wanted a person of high character to be representing you in that august body.

Over time, with increasing partisanship and tribalism, that matters less and less. The kinds of things that come out of the mouths of senators . . . I obviously don’t think the parties are the same. I think that you can find a lot more I-can’t-believe-he-said-that things from the Republicans than the Democrats.

The point is that, for the most part, voters don’t care because they’ve become so polarized that, really in a lot of places, as long as the guy is a Republican, it doesn’t matter what he says.

COWEN: Are there potentially beneficial changes you think we should at least consider making to the US Constitution?

KRUGMAN: I’m reading a lot about the Supreme Court discussion now, and I have to say, some people have been suggesting that, instead of lifetime appointments to the Supreme Court, we should do 18 years, which is probably enough to insulate from short-term political pressures but ends this . . . at least reduces the extreme drama where, when somebody finally collapses, then all hell breaks loose and would basically give every president a chance to nominate two Supreme Court justices. That sounds like something that would work.

But in many ways, I think what we really need to do, if we can, is to recreate the kind of society that supported a more reasonable political process, which means reducing income inequality.

COWEN: Let me throw out a number of ways we might do that, and tell me what you think. Universal basic income.

KRUGMAN: I’m still debating with myself over UBI. The pro is that its automaticity is a big thing. It matters a lot that Social Security and Medicare are just there. No one asks, “Do you need it? Do you deserve it?” It’s just there, and UBI would have that character.

On the other hand, it’s expensive. If you make it generous enough so the people who really, really need help get it, then it’s a lot of money. If you try to keep the price down, then it’s not good enough. What we have now is a bunch of means-tested programs, which are a lot more generous to people at the bottom than a skinny UBI would be.

So I’m actually unsure, but that’s a possibility. That would only really make a big difference at the bottom, and I think we need to do more further up the scale.

COWEN: Reparations for descendants of slaves.

KRUGMAN: It’s certainly just, but I find it hard to believe it’s going to happen.

But that’s not going to change the structure. If we were really going to talk about justice, it would make sense. There will be a fair number of people who say, “Well, my grandparents or my great-grandparents came over in 1915. Why should I be liable for this?”

But on the other hand, our country was built, in large part, on an incredible injustice. But that’s not going to change the structure. That would be a one-time thing.

COWEN: But symbolic actions can matter. Some of the Supreme Court debate is about symbolism.

KRUGMAN: Look, I think that going after Confederate monuments is a . . . You can say, “What difference does that make in people’s lives?” Well, it’s actually taking away some symbols that say that violent action on behalf of slavery was a good thing.

That’s why the monuments were put in there in the first place. They weren’t actually put in in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War in memory to the heroes. They were put in during the Jim Crow era to remind people of the importance of keeping those people in their place.

That’s the kind of symbolic action I certainly think makes sense.

COWEN: Ending the war on drugs and moving to either decriminalization or legalization. Would it help our cities or hurt them?

KRUGMAN: It probably would help, but I’ve put in no thought at all on drugs. I’ve just done no homework.

COWEN: Immigration policy. Maybe your views on this have changed over time. If you could set an ideal immigration policy for 2018, what would it be? How would it impact income inequality?

KRUGMAN: First, this is one of those areas where my views have changed. If you’d asked me about it 20 years ago, I basically went with a simple model of the labor force being workers with different levels of education. Immigration of low-education workers would widen income inequality. Then you could ask about some of the other effects and dilemmas and so on.

But I’ve been mostly convinced by evidence that says that an immigrant with a high school degree or less equivalent is really not competing head to head with native-born workers who have similar educational credentials. It doesn’t look like they’re filling the same jobs. It doesn’t look like they’re competing in the same labor markets. So I think the income distribution effects of immigration are actually much less than we thought.

COWEN: The backlash effects that, if too many foreigners enter too rapidly, a lot of native-born Americans become Trump supporters. How much does that worry you?

KRUGMAN: My view on immigration has always been that if you aren’t at least somewhat conflicted about it, there’s something wrong with you. If you want to have a strong social safety net, which I do and most people do if actually pressed on it, then completely open borders is going to get in the way. Whether or not it’s really going to bankrupt the system, the sense that lots of people are coming in to take your benefits is going to be a problem.

My view on immigration has always been that if you aren’t at least somewhat conflicted about it, there’s something wrong with you.

On the other hand, not allowing anybody in is, from a global welfare point of view, is a terrible thing because one of the best ways to improve people’s lives is to give them a chance to move to a place where they’re more productive.

And there are good reasons to think that just our own economic prospects are enhanced by immigration. So some kind of inevitably awkward compromise is what you’re going to do. Then the question becomes, “How many million immigrants a year are we talking about?” That’s a hard question to answer.

Restricted immigration, but not slamming the door, has got to be the right place to be. This is America. Diversity has been our huge strength over the centuries. It’s a real betrayal of our own history and of our prospects to turn it off.

By the way, I’m sitting here at CUNY, which is the quintessential children-of-immigrants school system.

COWEN: As is my school now, George Mason.

KRUGMAN: And it continues to fill that role. It did, of course, in previous generations . . . Janet Gornick — in the office next door, runs the Stone Center — and I are both CUNY babies. Her father went to CCNY and mine went to Brooklyn College. The story is the same but the ethnicity is different now.

COWEN: In 1996, for the New York Times, you wrote a very interesting essay called “White Collars Turn Blue.” I took this, on your part, to be a speculation, not an actual prediction. You mused about the possibility that maybe the returns to education would fall dramatically because of automation.

Do you think this has in any way come about?

KRUGMAN: The Times actually assigned, told people to write things from the perspective of a century from now, looking back, and I was the only one who was willing to do it straight.

COWEN: You predicted ride sharing in that piece, by the way. I don’t know if you remember this.

KRUGMAN: Yeah, it was fun. None of it was entirely serious, but yeah, there is this question.

At the moment, college degrees still carry a significant wage premium. But there is a question in many ways, in the longer run — I think I did say that — a lot of the things we think of as being high skill, requiring lots of education, are actually the kinds of things that computers can, in the end, do.

AI, or machine learning, whether that’s really AI or not, but it can do a whole lot of stuff that we thought of, not very long ago, as being the stuff that you have to go to school for years and years to achieve. Whereas robot plumbers are still quite a ways off because the material world tends to be full of unpredictable, hard-to-model features.

The idea that we’re always going to be spending huge resources or that it will always make sense to put a lot of effort into higher education is at least arguable. I think the idea that we could become a society where education goes back to being a status symbol for the elite is a live possibility.

On US voters

COWEN: If I think a lot of your criticisms of the Republicans, of Donald Trump, as I read you, very often you’re saying that what’s wrong here is really quite obvious. So, that it’s still happening, is your view that somehow shame has become too weak a force? Or is it asymmetric information?

Is there simply some kind of permanent lock that bad forces have over various processes? Kind of the micro foundations of how some very obvious wrongs could persist.

KRUGMAN: Oh, sure. We have to ask why. The question is, for different people, why do certain wrongs persist? Of the question, why do people continue to claim that cutting top marginal tax rates has huge positive effects on growth? A proposition for which there is zero evidence.

The answer is, who benefits from the perception that cutting top tax rates is good for growth? [laughs] That’s almost a question that answers itself. It doesn’t take a whole lot of money, relative to the amount of wealth in our society, to create a whole structure of institutions that reward people who will endorse supply-side economics.

COWEN: But at the voter level, most voters don’t know that debate. They see Republicans doing bad things. Republicans are still getting re-elected. We might have all Republican governors in New England, which to me is deeply strange.

KRUGMAN: At the voter level, there’s two things. The Republican governors in New England is a little weird because they often don’t behave like Republicans.

I was in New Jersey. I was in Massachusetts, both places that are deep blue, so much so that you end up with kind of routine machine politics, corruption among the Democrats, and people elect Republicans just to get a break from the machine. They don’t necessarily pursue policies that are anything like those of the national party. That’s an exceptional case.

Ordinary people, people with real lives, real jobs, people who aren’t paid to think about abstract policy issues are, understandably really, more poorly informed that those of us who push around words and symbols for a living can easily appreciate.

If you ask people, do they actually know what the policies are being propounded, if you ask them do they know what Republican healthcare policies actually are — maybe more so now than a year or two ago — but still mostly not. People are poorly informed.

Of course, sometimes they’re actively misinformed by Fox News or something. It’s instructive, being out there in public, writing for a newspaper, even writing for the New York Times, and then looking at the mail you get.

Leaving aside the crazy and hate stuff, but just the sort of ordinary citizens — they’ve heard from somebody that there’s a plan to replace the US dollar with some global currency.

You know and I know that’s ridiculous. But these aren’t necessarily stupid people. They’re not devoting a lot of time to public affairs. Of course, the news environment is — leave aside, again, the partisan media — tends to be very information scarce.

Years back, during the 2004 campaign, I went through transcripts for network news over a three-month period on the issue of healthcare, to find out how much would somebody who got their news from watching the TV news programs have learned about Bush versus Kerry on healthcare.

The answer was, not one thing. There were a couple of stories about how their healthcare strategies were playing politically, but there were none at all about the actual content of their healthcare programs. So why would we expect voters to necessarily recognize bad ideas?

COWEN: A lot of times you remind me of the earlier progressive historians: the notion special interests and self-interest is rife, that it’s quite obvious that someone needs to blow the whistle, that there’s a kind of ongoing moral struggle in America. A lot of it’s about economic self-interest.

Is that an identification you either agree with or make self-consciously, or you just think it’s evolved that way because of historical constants?

KRUGMAN: No, I think it’s evolved that way. First of all, that’s always been somewhat true. You’ll always need to be blowing the whistle on self-interested stuff that’s going on in the hope that the public won’t understand it.

But it’s also true the progressive movement arose during a period of great income inequality and corporate dominance of a lot of politics. And here we are, in an era of great economic inequality and corporate dominance of politics.

So of course, we’re going to sound the same when critiquing a lot of the conventional wisdom.

COWEN: You’ve written a few times that you started with history before economics, but never explained that much besides mentioning Isaac Asimov’s Foundation Trilogy. A funny kind of history, but still a historically oriented series of novels.

What else did your early history background consist of? And how has that shaped your thought?

KRUGMAN: I took lots of courses. In my nonfiction reading, history is dominant. I just find that the story of the past, whether or not it actually translates into any direct parallels with the present, is a great way to have a sense of the world.

COWEN: You have a paper with Venables from the mid ’90s in the QJE. I think it’s called “Globalization and the Inequality of Nations.” It’s really a paper about history. For some reason, it’s become somewhat neglected.

The notion that, as transportation costs fall very low, that nations on the periphery come back at the expense of the nations in center — do you think that’s what’s happening to the world today?

KRUGMAN: I think we don’t really know.

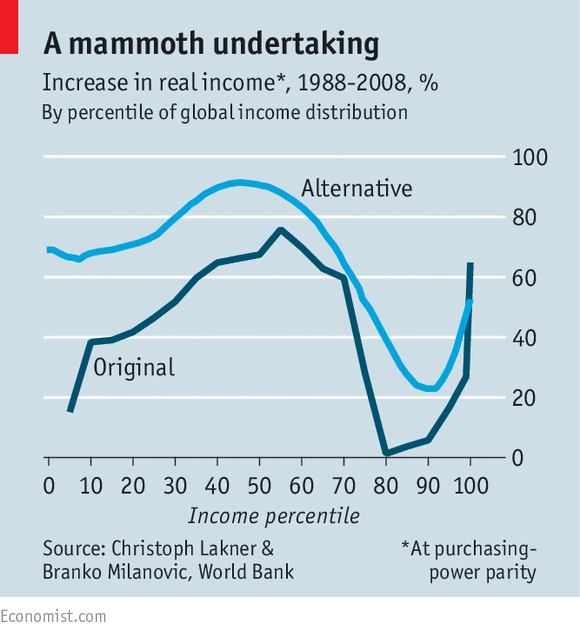

Just around the corner, Branko Milanovic has his office, and Branko has the famous elephant curve that shows income growth around the world.

There’s a clear transition after the late 1980s as globalization really takes off. You start to see twin peaks: the global one percent pulling away from the rest, but also the global middle — the Chinese middle class, really — experiencing rapid growth, with a trough in between, which is the working class in advanced countries.

Is that actually because of globalization? Or are common factors driving both globalization? I don’t think we really know. It’s certainly a nice story.

Tony Venables and I were having some fun. We were working on economic geography and realized that one way you could cast the model would be one that would give you this U-shaped behavior in which you start from a world of high transport costs with very little globalization.

Reduce them some, and the world differentiates into an advanced region and a peripheral region. Then reduce them further, and the peripheral region, with its lower costs, makes a comeback. That’s a nice story. It’s probably too simple to capture what really went on.

On infrastructure

COWEN: What’s your view on NIMBY versus YIMBY? Do we need to build more in America’s major cities?

KRUGMAN: Oh, yeah. I’m a total YIMBY on that. There are reasons for certain kinds of zoning restrictions, but that has very little to do with most of the reasons we don’t build housing.

If you like, it’s a place where at least a lot of liberals are wrong, and the de facto policies of a lot of conservative places are right. You want to allow more building. New York is in many ways a thriving, successful example of what you can do. We make it way too hard to build housing for people who want to come here, and the result is to price out a lot of people who really should be part of this experience.

COWEN: Henry George’s single land tax — would you consider it as a means of both encouraging building and reducing inequality?

KRUGMAN: I just haven’t done my homework on that.

COWEN: If you think of the international supply chains that spread across many countries — Richard Baldwin has written on this. You have yourself.

Do you think we’re now in an era where those chains are, in essence, contracting or collapsing? And what is now done in China may end up being done in Mexico or NAFTA? And that will unravel? Was it all too utopian to begin with?

KRUGMAN: It wasn’t utopian. It worked. It is true that global trade really soared from about 1990 to 2010 and then sort of leveled off.

It does look as if it was a one-time thing, the combination of trade liberalization in emerging markets and reduced transportation and transaction costs — because it’s not just the shipping costs, but it’s the costs of getting things on and off the ships, and all that led to it. But it looks like it was a one-time surge in trade, this value-chain kind of trade.

There’s some indication that there was a little bit of overreach, that businesses, in search of saving that last penny, built international logistics chains that were just too complex, too subject to delays, disruption, and that there wasn’t advantage in moving stuff back closer to home. So there probably would have been some retrenchment anyway.

Now, you tell me what’s going to happen with our trade conflict.

COWEN: It’s perpetual. Supply chains will contract and become more regional.

KRUGMAN: But how big? How severe? First of all, even the regional stuff — I have to say that the trade policy guy in me is, in some ways, enjoying this. It’s been, historically, for a long time, a pretty boring subject.

COWEN: That’s right.

KRUGMAN: World trade was almost free; nothing was happening. Now, all of a sudden, not only is stuff happening, but it’s happening in unpredictable directions. Even after the 2016 election, if you had told me that we would be making nice with Mexico but in dire conflict with Canada . . .

[laughter]

I have no idea how far this goes. I suspect that . . . Let’s put it this way. A good guess would be that the regional trading agreements are more robust in the end, just because business has so much of a stake in maintaining them. But who knows?

COWEN: Given the trends in economic geography we see, the trends and evolving technologies, do you think the two American coasts will become increasingly economically important? Or will, at some point, that trend reverse itself?

KRUGMAN: It really looks as if agglomeration economies have become more important. We really do see a migration of economic activity to the areas that are already rich, and that is a little interesting.

There was a debate — it still goes on a bit — there was a debate 20 years ago: With the internet, distance shouldn’t matter. Why won’t people relocate to where land is cheap and there’s no traffic?

It doesn’t seem to happen. There seem to be other factors that make it more, not less, desirable to locate where the action is. As far as we can tell, it’s still going in that direction. I’m a little reluctant to be sure that it continues.

Ex ante, it wasn’t at all clear which way it was going to go. To the extent that we can model this at all, which is pretty limited, it seems to be there are countervailing factors. I don’t think anyone had enough insight to know that it was going to turn out that the big metropolitan areas were going to be winners rather than losers from this trend.

On macroeconomics

COWEN: A few macro questions. How much do you worry about slowing population growth as a factor for an ongoing slowing of aggregate demand?

KRUGMAN: Very much. There’s a little story here. Larry Summers became famous for advocating the idea that we’re facing secular stagnation. I had written about the same time, or even a month or so earlier, along the same lines, except what I wrote was very poorly formulated and unreadable.

Larry came up with this crystal clear explanation of the issue. So he gets all the credit, and what’s even worse is he deserves it. So I get really pissed because I blew it on that one.

I think that the secular stagnation–type stories, the stories that say that, with falling population growth, we have a hard time generating enough investment demand to use the desired savings, so that interest rates tend to be low even when times are good and tend to hit the zero-bound way too often, is a good story.

It’s not 100 percent certain that it’s right, but I think it’s a good story. The first dress rehearsal for the difficulties that we’ve all had since 2008 was Japan. Japan famously is the place where declining working-age population kicked in well before it happened in the rest of the advanced world. I think it’s a big issue.

COWEN: Political risk aside, which we’ve already discussed, what do you think is the number-one danger to the global economy right now? Is it corporate debt? Is it China? Is it Turkey plus Argentina? Something else?

KRUGMAN: I’ve been arguing that the next recession will be a smorgasbord recession. It will be a mix of all of these. There’s no one huge thing that stands out, but there’s a bunch of things where it looks like the Minsky financial cycle.

After a long period without shocks, people get complacent. They start extending themselves, taking risks, taking on leverage that creates new risks. That all tends to proliferate. The thing that makes it dangerous is not so much that there’s this one huge weakness as the fact that, in a typical recession, the Fed cuts interest rates by something like 600 basis points.

At the moment, the Fed only has 200 basis points to cut. It ties in with the question about secular stagnation, is the fact that we’re starting from a position of really low interest rates, which means that monetary policy is not very effective.

We’re accumulating no one huge problem in the economy, but arguably a bunch of smaller ones. If several of them come to a head together, then we’re set up for a very difficult business cycle again.

COWEN: Janet Yellen mentioned yesterday, I read, that the Fed may need to raise interest rates again at this point. If you view that matter different than she does, how would you trace that difference back to underlying frameworks?

KRUGMAN: That’s an interesting question because as far as I can tell . . .

COWEN: She’s very dovish. We all know, right?

KRUGMAN: Yeah. As far as I can tell, her framework is not very different from mine, and what my framework was telling me is, don’t raise rates because, actually, a somewhat higher inflation rate would be extremely useful. If you don’t raise rates now, you can get up to somewhat higher inflation, which means that you’ll have room to get real interest rates lower during the next slump, and that would be a good thing.

So why doesn’t Janet Yellen see it that way? My answer is that, for reasons that are less intellectual and more almost social, anyone who’s been associated with central banking is really wedded to the 2 percent inflation target.

If you accept that the 2 percent inflation target is sacrosanct, then yeah, there’s pretty reasonable grounds to think that, although inflation has been very low to come along, the chances that, if the Fed doesn’t raise rates further, inflation will start to creep noticeably above 2 percent are reasonable, reasonably high.

If you take that as your constraint — inflation must not be allowed to substantially exceed 2 percent — then yeah, you need to raise rates, but I don’t accept the starting premise.

COWEN: If we have a service-sector economy where contracts are not renegotiated all the time — workers’ bargaining power, at times, will be weak — would the American public put up with, say, a 4 percent inflation rate, knowing their real wages would be cut into, and they would have to struggle to get that back every time there’s a bargaining cycle?

KRUGMAN: That’s a good question, although I’m not sure that the service economy aspect really makes a big difference to the extent that . . .

COWEN: But there are fewer unions, right?

KRUGMAN: There are fewer unions. But on the other hand, fewer unions might mean that more wages could arguably become more flexible than not. What is true is we don’t have COLAs. Actually, I’m showing my age by even knowing what a COLA is.

COWEN: Cost-of-living adjustment.

KRUGMAN: At the moment, it’s not the public is saying 4 percent inflation or 3 percent inflation is unacceptable. It’s all the central bankers who are there. I am actually old enough to remember a 4 percent inflation economy, which is the second half of the 1980s, and I don’t remember people complaining bitterly about inflation during those years. It felt OK.

We shouldn’t be inventing a public objection without clear evidence that it’s really there. Meanwhile, the economics that says that a 4 percent inflation rate makes a lot of sense, I think, is pretty strong. The economics that said the 2 percent was enough has all turned out to be wrong, given the experience of the last 10 years.

COWEN: In your view, how well run is New York City as an entity?

KRUGMAN: Not very. Compared to what? Actually, I like de Blasio. I actually think he’s done some really good things. What he’s done on education, and even on affordable housing, is actually quite substantial. But the city is so big and the problems are so large that people may not get it.

I will say, it is crazy that you have a city that is so dependent on public transportation, and yet the public transportation is not actually under the city’s control and has clearly been massively neglected. I don’t suffer the full woes of the subway, but I suffer some of them, even myself.

The city could be run better than it is, but it’s certainly not among the worst-managed political entities in the United States, let alone in the world.

COWEN: Purely local control of the subway to internalize those gains, you think would be a good idea?

KRUGMAN: Probably it would be. It would mean that the complaints would be felt sooner, that there would probably be less . . . The subway is desperately strapped for money but has spent a fair bit on things that seem to be more about prestige than actually improving the daily ride.

I don’t know. I’m not sure what else is important. Someplace where de Blasio I think is in the wrong: We could really use a congestion tax. I guarantee you that outside the window just behind me, there is a standing traffic jam because there always is.

COWEN: Sure.

KRUGMAN: I’m not sure exactly how the politics would . . . what do I know about political institutions and their effect? Only amateur, only what anybody who reads the newspaper does. But there are things that could be done better.

COWEN: Bringing down infrastructure costs, in part to be able to build more. What’s the trick there? It doesn’t seem to be mainly labor unions. Why can’t we do it?

KRUGMAN: It seems to be there’s just a lot of cross-cutting interests. It’s not mostly the labor unions. It does seem to be something about some combination of opposing bureaucracies. I don’t know. It is a remarkable thing, though. Why everything is so expensive, I still haven’t figured it. That’s not a New York problem. That’s an everywhere problem.

COWEN: Sure. But some areas — London seems to run much better than New York.

KRUGMAN: That’s right. It’s a US problem.

COWEN: Cleanliness, certain kinds of public order . . . even though New York is safe now. But it doesn’t look like a well-run city in every way when you walk past garbage, say.

KRUGMAN: There’s some of that. Although, actually, I would say that I remember New York 40 years ago.

COWEN: So do I.

KRUGMAN: It’s inconceivable how much it’s gotten better.

By the way, this is not a recent thing. I don’t think New York gets enough credit for the brilliant innovation, I don’t know how many decades ago, of the four-track subway system, with express and local trains. It makes a huge difference in the livability of the city and the ability to commute within it.

There’s something in the US build . . . how did we get there? We used to be a great country on infrastructure. We used to be the great builders of the world.

COWEN: Incredible. The best, right?

KRUGMAN: Now we can’t seem to . . . a mile of anything costs at least a billion dollars, and I don’t know why.

COWEN: What do you think of the William Baumol cost disease hypothesis? There are just some sectors where rising wages mean they cost more and more and become less effective.

KRUGMAN: This is obviously true of some things, but it’s not clear that that applies to infrastructure. The old Baumol hypothesis was very much, service costs were always going to rise relative to goods production. But that’s not at all clear more recently where, at least during the productivity spurt we had from ’95 to ’05, a lot of it was in the service sector.

So I think it varies. With changing technologies, the cost disease may be afflicting different sectors. Machine learning already means that a lot of stuff that we used to think of as cost disease–afflicted service sectors has now actually gotten startlingly cheap.

On things interstellar

COWEN: Will there ever be interstellar trade in intellectual property? You send your technology to a planet far away. It arrives much later, of course. Or you trade Beethoven to the aliens in return for a transporter beam? Can this work? You’ve written a paper that seems to indicate it can work.

KRUGMAN: I wrote a paper on the theory of interstellar trade when I was an unhappy assistant professor. Are there any happy assistant professors? [laughs] I was just blowing off steam. But it’s an interesting question.

COWEN: It could become your most important paper, right? [laughs]

KRUGMAN: We could imagine that there would be some way. We’d have to find somebody to trade with, although it’s the kind of thing — if you try to imagine interstellar trade for real in intellectual property — it’s probably the kind of thing that would be more like government-to-government exchanges.

It sounds like it would be really, really hard, although some science fiction writers are imagining that something like Bitcoin would make it possible to do these long-range . . . I don’t think something like Bitcoin is even going to work here.

One might hope that in the 23rd century or something, that we’ve actually gotten to the point where we will give, we will share our knowledge with the aliens out of our goodness, and they will do the reverse. The Star Trek universe appears to be a postcapitalist society, so who knows?

COWEN: If you can send humans out into space at near light speeds and bring them back, does that mean real interest rates have to fall to zero? Many years could pass, and you could save and come back a trillionaire.

KRUGMAN: First of all, actually, it’s not clear that the returns are high enough to make that an attractive proposition. There was an old, old story about the guy who put a dollar in the bank and left it in a perpetual trust fund and eventually ends up owning the economy.

But in fact, R has been less than G on average, historically, so that doesn’t actually happen. I think the same thing is true. You don’t need interstellar trade for that, right? You could have cryonics. But the fact of the matter is, that would not have worked.

If you had found yourself a way to do a Rip Van Winkle, with intent to reclaim your invested money from a century ago, I don’t think you would have done all that well. I don’t think that’s going to be the constraint.

COWEN: Star Trek versus Star Wars. Which do you find more interesting?

KRUGMAN: Oh, boy. Good thing about Star Trek is that there were lots of shows and not three absolutely horrible movies that I refuse to watch. I don’t know. I’ve actually never been all that into either one. Purely nonintellectual stuff.

I think the use of iconography, of just the way things look in Star Wars is a lot more interesting, but the social speculation in Star Trek is more interesting. So, both have their virtues, and the truth is, I’m not all that into either one.

COWEN: What would be a science fiction novel that maybe people don’t all know about that you would recommend that influenced how you think about the world? We know the connection to Asimov, Iain Banks, the Culture series. What else?

KRUGMAN: Charlie Stross — almost everything he writes. Charlie Stross, if people don’t know, is an English writer but living in Edinburgh. Incredibly prolific and writes these multiple linked series of books.

COWEN: And he blogs.

KRUGMAN: And he blogs, which is also great fun. The Merchant Princes novels involved world-walkers, people who can step in between alternative universes. They come from an alternative timeline in which North America is this backward medieval society. They can step back and forth to our timeline.

You would think that they would bring back our technology and transform everything. In fact, they have some of our technology, but their society stays medieval and backward. They basically used their world-walking ability to be drug smugglers.

I’ve actually written about this. This is a series that’s about development economics, about having access to advanced technology doesn’t make you an advanced society, and how hard it is actually to achieve social change.

COWEN: The dream of a generalized psychohistory is outlined in the Foundation Trilogy. Will it ever be possible?

KRUGMAN: Probably not.

COWEN: It’s just a motivating dream?

KRUGMAN: That’s what I always wanted. That’s why I went into economics, as I say. I’ve wanted to be a psychohistorian.

The reason we can get even as far as we do in economics is that economics is about the simplest, crudest aspects of human motivation and behavior — getting and spending, basically. Even there we don’t do too great, but at least we have a pretty good idea of what it is people are trying to do. Get beyond that, and it gets way harder.

COWEN: Returning to nonfiction, is there an economically viable role for humans in space?

KRUGMAN: That’s unclear. At the moment, it doesn’t seem obvious that there is if you try to think about the things you can actually use space for. Colonizing space doesn’t look like a great thing to do.

There’s a lot of things you can imagine. In fact, space is already extremely useful for communications and could become useful for some kinds of manufacturing. But it’s hard to see that any of these things require that there be people up there.

COWEN: What about diversification? The earth is vulnerable, if only to asteroid strikes.

KRUGMAN: There’s a case to be made for it, but is there an incentive to do it?

COWEN: Who internalizes that gain?

KRUGMAN: Yeah, who internalizes? A lot of space, a lot of science fiction is built around the analogy between space and the frontier, but it’s not much like that. There’s not rich land waiting to be exploited. There’s an extremely hostile environment. I mean, we haven’t colonized Antarctica, either.

On the Paul Krugman production function

COWEN: To finish up the discussion, a few questions about what I call the Paul Krugman production function. In the 1990s, you wrote a well-known paper. It’s called “How I Work.” It was giving people tips, not quite advice for other people, but how it is that you get things done.

A few decades have passed since then. What do you think you’ve learned about getting things done that was not in your paper “How I Work”?

KRUGMAN: I put in a lot more effort. First of all, I still think that reads pretty well as a description of how I work. At the time I wrote that, though, I was writing for academics. Now, I do a lot, obviously, of public intellectual stuff. So you would probably have to add some principles about thinking about how this reads to people who are intelligent but come at it with no background.

One of the principles I think about all the time with the Times is, nobody has to read your column, so you have to have a hook at the beginning, and you have to have a zinger at the end. [laughs] Style matters, as it should because people have scarce time, and you have to give them a reason to spend time with you.

And of course, these days, with Twitter, which it turns out, I guess, if numbers are an indication, I do well at. There, I think the most important thing is to just not think about how many people are reading it. Dance as if no one is watching, tweet as if no one is reading. That just seems to be the way to make it work.

Dance as if no one is watching, tweet as if no one is reading.

COWEN: You mentioned having had, around 1987, a kind of temporary dry spell in your career. How is it you pulled yourself out of that?

KRUGMAN: No idea.

COWEN: It just happened.

KRUGMAN: It just happened. I was thinking about lots of things, running around to conferences, and somehow that gelled into a series of good ideas. I guess, given the trajectory, the dry spell was the anomaly.

COWEN: If you were given a free decade you could take off and then return to the life you had, what would you do with that decade?

KRUGMAN: Oh, God. That’s hard. I’m 65 years old. I’m pretty set in my ways. It’s hard to think about.

COWEN: You could read more books. You could travel around.

KRUGMAN: I’m sort of doing that already. That’s the thing. I’m not working as hard as I was.

This past summer, I was trying to decide between two bike trips in Europe that both looked really appealing. Then I said, “What the hell.” So I did both of them. I’m taking more time to see the world, do stuff.

The great luxury of being where I am now is the end of ambition. There are no more notches I need to put in my belt, no more rungs I need to climb on the ladder. Aside from the fact that the world is going to hell otherwise, I’m just basically having a good time.

The great luxury of being where I am now is the end of ambition. There are no more notches I need to put in my belt, no more rungs I need to climb on the ladder. Aside from the fact that the world is going to hell otherwise, I’m just basically having a good time.

COWEN: Is that utopia or dystopia, however? Because presumably to have arrived at your current point, you’re driven in some set of ways. Now, you’re not sure what the next step is.

KRUGMAN: There was a period, I have to say — I think I’m over that hump, but we’ll see if I go crazy in the near future, but there’s a moment when you . . . I suspect that quite a few people, after getting a Nobel Prize or something, actually experience a spell of depression because now what? [laughs]

I had a little bit of that, but that’s a point where you just find things that you’re interested in. You know that whole business about “Do what you love and the money will follow”? That, of course, is garbage. But if the money is already there, you’re being paid a nice salary, then you can do what you love.

COWEN: Let’s say a very smart 20-year-old came to you and said, “I want to be the next Paul Krugman,” and they meant as a public intellectual, not as a research economist. What advice would you give them?

KRUGMAN: The truth is I have no idea. I would say, maybe, that it’s just be interested in a lot of things, but when you find something that really grabs your attention, work at it seriously. Figure stuff out.

Curiosity, as opposed to intellectual complacency, is the big thing. If you don’t feel that the explanations you’re being given of something — whether it’s international trade patterns or the Japanese slump or something — if you don’t feel that the explanations quite hold together, then worry at it. Try to find something.

Scratch that itch. Don’t let it go away. Whether that will turn out to do what you want it to do, I don’t know.

COWEN: For a budding research economist, would it, in fact, be the exact same advice?

KRUGMAN: Oh yeah, except that what I would say is that at this point, don’t do what I did, which was very heavily theory-oriented, simple models, because there’s always a possibility of that, but now we are in this golden age of empirical work.

The same advice that we used to give our grad students: Find facts and data that have not been heavily worked over, and look for anomalies or look for natural experiments that shed light on disputed issues. Go out there and look at the world.

I suspect that stepping beyond traditional economic methodology is going to be productive in the years ahead. We just had the Rainwater Lecture here. We had a lecture from an ethnologist, who goes and talks to working-class fathers.

I was blown away by . . . It’s a totally different research method from anything we do in economics, normally. It’s totally different and, of course, requires a degree of personal interaction with the subject you’re studying that I would find terrifying.

But that made me think, “I wonder how many insights might we get by doing things in a way that’s very different from anything that’s now part of the standard economics research paradigm?”

COWEN: Paul Krugman, thank you very much.

KRUGMAN: Thank you.