Watch the full conversation

Read the full transcript

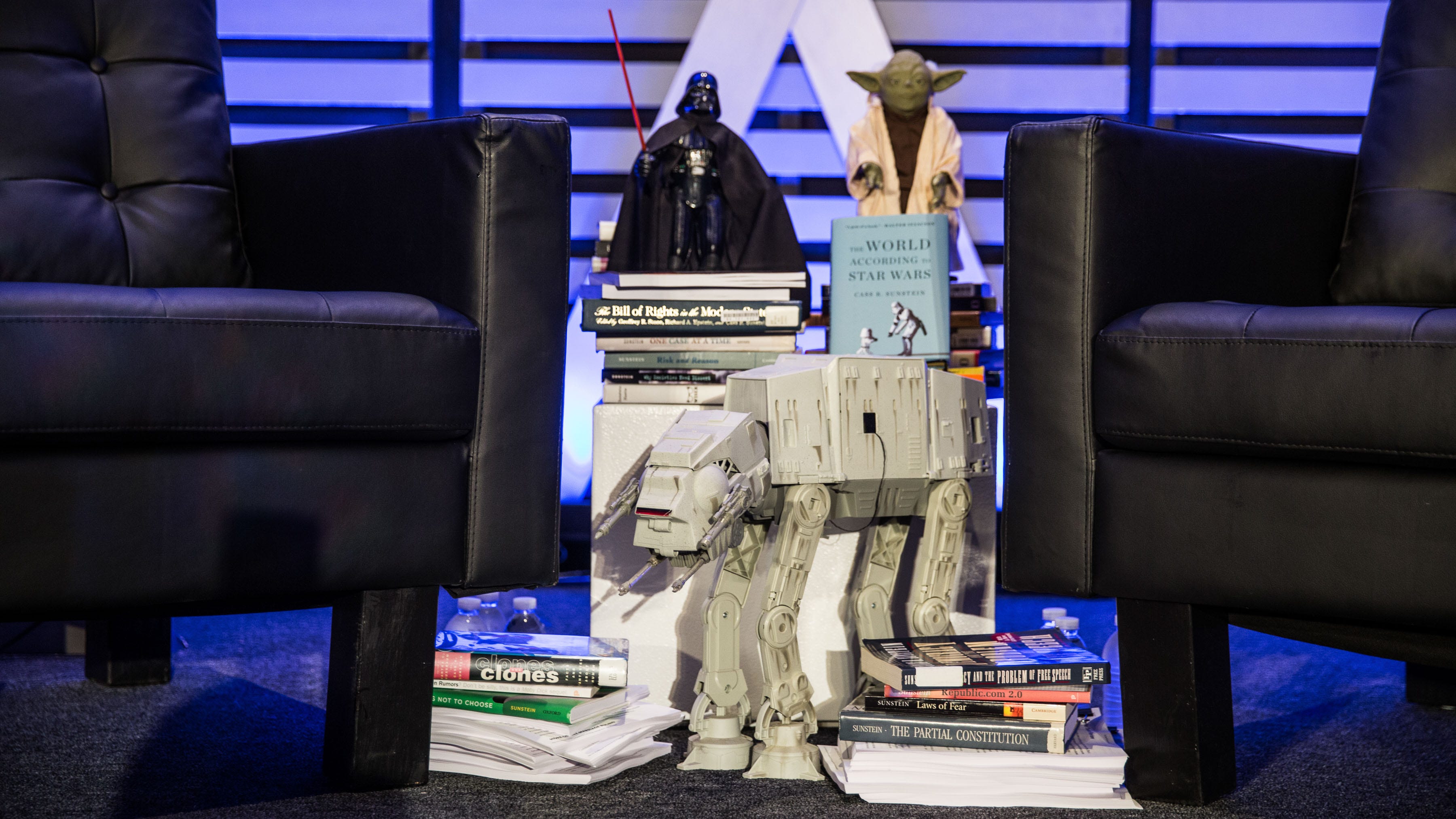

TYLER COWEN: The Force is strong with this one. Cass is by far the most widely cited legal scholar of his generation. His older book, Nudge, and his new book on Star Wars are both best sellers, and he was head of OIRA [Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs] under President Obama from 2009 to 2013. Powerful, you have become.

So tonight I’d like to start with a survey of Cass’s thought. We’re going to look at legal theory and then go to Nudge and then consider Star Wars, how it all ties together, and then we’re going to talk about everything.

On Sunstein’s legal philosophy

Let’s start with your legal theory. If I think of Richard Epstein, I think of classical liberalism, some mix of rights and utilitarian reasoning. If I think of Dick Posner, I think of pragmatism mixed with law and economics. If I think of Dworkin, it’s legal interpretivism. If it’s Cass Sunstein — your legal theory in a nutshell — how should I characterize you?

CASS SUNSTEIN: Well, I think I’d use three words: incompletely theorized agreements. And I don’t think anyone’s ever marched under a banner with those three words on it, but in a way I think that is America’s banner. So the idea of incompletely theorized agreements is often we can figure out what our rights are and what to do without committing ourselves to a particular conception of the foundations of morality or without knowing exactly what we think about the foundations of morality.

So you can have a free speech principle that says speech is protected unless there’s a clear and present danger, even if you are a welfarist and think that the idea of respect for persons is metaphysical gobbledygook.

You can believe in the “clear and present danger” standard if you are a Kantian and think that people have a right to say what they wish and go their own path and think that welfarism is a form of barely human robot philosophy. You can be an Aristotelian and say the same thing.

You might be just philosophically indifferent and think that, if you want to have a society which figures out what’s true in some way that is not highfalutin, the “clear and present danger” test is right. I could give a zillion examples. I won’t. But our freedom-of-speech principle reflects an incompletely theorized agreement.

COWEN: In some ways it’s like the opposite of Star Wars. Star Wars — it’s chock full of metaphysics. And here you’re saying we don’t really know about metaphysics. How far can we get with only a minimal amount of agreement? Sometimes you’ve called this judicial minimalism, right?

Take a case going on right now — very complicated case. North Carolina, transgender individuals’ bathrooms, two different points of view. Your perspective of minimalism — is there a way you could apply it to — ?

SUNSTEIN: Yes.

COWEN: Give us the right solution.

SUNSTEIN: So, I’d need to say a lot about the particulars of that to resolve it. But to resolve the transgender bathroom issue, we need to think, I think, first about questions — kind of mundane questions about jurisdiction and authority. And I’d like to avoid big questions about sexuality and what people are like unless you have to get there.

And so, one question is what authority the states have; what authority does the federal government have? As a presumption, the states have authority over bathroom stuff. On the other hand, the federal government has some regulatory authority under the Civil Rights Act.

And if you’re falling asleep a little bit because I’m not talking about transgender in the large, I’m sad you’re falling asleep but a little happy that hair isn’t on fire, because one way democracies work well is they put people’s hair on fire very rarely. They try to use issues of democratic process and who has the authority to do what as a way of allowing us to live together peaceably, notwithstanding our disagreements.

There’s a good argument at least that the federal government has regulatory authority under the civil rights laws to figure out what counts as discrimination, sex discrimination in particular. Whether in the end this is a convincing argument, I’m kind of bracketing that, but that is a minimalist direction. It wouldn’t say anything super large about what sex equality means; it would say something more modest about who has authority.

COWEN: Let’s take you and Dick Posner as theorists of legal reasoning. He’s also not a big proponent of metaphysics, but you and he end up at different points — especially earlier Dick Posner, right? He’s actually moved closer to you. What’s the empirical variable that you and Posner disagree about that accounts for where you end up and where he ends up?

SUNSTEIN: OK. Well, we’d have to figure out where exactly we differ. Early on, he had a view — and this is not an empirical disagreement — but early on he had a view that wealth maximization is what judges should try to maximize.

COWEN: Sure, but he’s moved away from that.

SUNSTEIN: Yeah, and I would consider that too sectarian a view. I think his view of judicial authority is a little too free-floating for me. Where we disagree, if we do — I think we probably do — is that I am more concerned about the need for stable rules that discipline judicial authority, even if it would be exercised wisely by some judges.

And Judge Posner, I think, is a superb judge whose judgement in particular cases is often excellent. But it doesn’t have a kind of rule-following character on some occasions that I think for most judges is a very important safeguard against the willful exercise of discretion.

On the metaphysics of nudging

COWEN: Now let’s go to your famous work on Nudge with Dick Thaler. And nudge is not direct physical violence — it’s nudge, right? Is that just a direct outgrowth of judicial minimalism but applied to regulatory policy — that here’s what we ought to all be able to agree upon without much in the way of metaphysical commitment, so it’s all one big picture — or not?

SUNSTEIN: It’s a great question, so I’ll give you a kind of “yes” and a “no.” The “no” is — when Dick Thaler and I thought about the idea of nudging, the notion was that choice-preserving approaches often have two really great features. One is, they preserve people’s ultimate freedom to go their own way. And the other is that it can — a choice-preserving approach can give welfare and longevity and everything good the benefit of the doubt.

So a GPS is a nudge.

COWEN: Right.

SUNSTEIN: It tells you the direction in which you probably ought to go if you want to get there expeditiously, the direction you want to go. And if you want the scenic route or the route that triggers feelings of nostalgia in you, go for it. Tell that little voice to be quiet; you’re going to go you own way. That’s a nudge.

And what Thaler and I thought, informed by behavioral science and behavioral economics, is that human beings don’t know how to navigate roads unless they are really trained. They might use heuristics for how to get to places — I certainly do — that often go wrong. And if you want to manage your savings portfolio, you might rely on rules of thumb that are going to make you less wealthy than would be good. Or you might have eating habits that aren’t so good, or you might get a mortgage that isn’t in your interest. And so, given human fallibility, nudges are often super important for well-being. They’re actually all around us, so a nudge-free world is actually literally unimaginable.

So we thought about, how can you — how can you get to good results while preserving people’s freedom, which is a great safeguard against private or public error. So, that idea doesn’t have much of a family resemblance to minimalism.

Minimalism is a way of telling the judges, “Be shallow,” which is not good in romance, but which is good often for courts; “Don’t get deep,” that might be too sectarian; and “Be narrow,” meaning, “Decide this case and not all cases,” on the ground that width, when it comes to a court, can be a recipe for self-embarrassment.

You decide an affirmative action case in a way that resolves all affirmative action cases, then you might be confounded by situations where either affirmative action is, let’s say, extremely important or is invidious. And your decision — okay, so that’s minimalism. But in terms of the — .

COWEN: That does sound like nudge to me. “What’s the thing you can get people to agree on?” Very context specific. It’s not a judge; it’s a regulator. But it’s like the unity of Cass Sunstein’s thought.

SUNSTEIN: There we go. There you’re completely right. So what appeals to me about nudging in part is in a sharply divided polity, a nudge can be — salute to you — a form of political minimalism. Where people might say, “You know, I don’t know what I think about climate change. But if you give me a fuel economy label that tells me something about how much money I’m going to pay this year — and tell me, by the way, something about the polluting content of the car — I’m for that.” So nudges often can attract appeal from people who would disagree about bigger stuff.

COWEN: Let me tell you some of my views on nudge, and then you respond. I view everything in life as a nudge, so in this sense, nudge per se doesn’t bug me. Some nudges may or may not work — fine, let’s discuss that — but I’m not offended by the nudge. But I see in the world so many people who hate the idea of nudge in a deep sense.

And if you view every point as being a nudge of some kind, you’ll also think, “Well, there’s no point of pure transparency we can nudge everyone to that’s the default.” So nudging is always a metaphysical commitment of some kind, and thus I worry there are conflicting impulses in you. There’s the “Well, let’s do this metaphysics-free,” like the minimalism.

But if everything is a nudge, and you’re choosing across all of these nontransparent points, there’s some deep metaphysical commitment in Cass Sunstein. And I want to get at what that commitment is and then tie it into a big theory of “Why do some people seem to hate this idea so much?” Do you see what I’m saying?

SUNSTEIN: I think — yes, I do. So — OK. So the economic analysis of law has had many good ideas. It’s had one great idea — like, world-transforming idea, I think. And the idea is, when you’re stuck, minimize the sum of the costs of decisions and the costs of errors. Now, that is not gripping stuff. But it’s profoundly true that if you don’t know what to do, figure out either a meta-rule or a particular decision that makes error costs low, meaning the number and the magnitude is small, and that makes decision costs low, meaning you don’t have to drive yourself crazy.