Last year, Tyler asked his readers “What Is the Strongest Argument for the Existence of God?” and followed up a few days later with a post outlining why he doesn’t believe in God. New York Times columnist Ross Douthat accepted the implicit challenge, responding to the second post in dialogic form and arguing that theism warrants further consideration.

This in-person dialogue starts along similar lines, covering Douthat’s views on religion and theology, but then moves on to more earth-bound concerns, such as his stance on cats, The Wire vs The Sopranos, why Watership Down is the best modern novel for understanding politics, eating tofu before it was cool, journalism as a trade, why he’s open to weird ideas, the importance of Sam’s Club Republicans, the specter of a Buterlian Jihad, and more.

Watch the full conversation

Recorded January 11th, 2018

Read the full transcript

TYLER COWEN: Good evening, everyone.

Ross is the youngest person ever to have been an op-ed columnist for the New York Times.

ROSS DOUTHAT: You had to start there.

[laughter]

COWEN: He is one of our best and most important thinkers. And in March he has a new book coming out called To Change the Church: Pope Francis and the Future of Catholicism. And, just to make this clear, this is the conversation with Ross I want to have, not the one you want to have.

[laughter]

COWEN: Ross, welcome, thank you.

DOUTHAT: Thank you, Tyler. It’s good to be here.

On Christology leading to individual liberty

COWEN: I’d like to start with something quite esoteric. Now, to prepare for you, I was reading the Calvinist theologian Rushdoony. And he argues the Council of Chalcedon in 451 AD actually enabled liberty through its Christology. The notion that you embed in Christianity — salvation through grace, rather than through self-deification — and this ends up meaning the state is not the savior, and the church and state thus eventually end up as opposing principles. And this is a kind of foundation for later individual liberty. Now, as someone who’s both Catholic and who has an interest in conservative and liberty-related ideas, what is your take on that account?

DOUTHAT: Sometimes I’m persuaded by a version of it, and sometimes I’m not. I think that there is a very natural story to tell about Western civilization, in which particular Christian ideas about the individual, the individual’s relationship to God, “Render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s,” and so on — that these sort of embedded ideas eventually develop into the constituent forms of modern liberal democracy.

And, in that story, you could argue either that liberal democracy is a kind of happy development out of original Christian ideas and Christian thoughts, or that it is a kind of rebellious stepchild who has sort of taken over the house and banished the parent to the attic. And I guess those are views that I toggle back and forth between, depending on what seems like the state of Western liberalism at any particular moment.

COWEN: So, as a Catholic, you have a kind of intermediate view on how important works are for grace. So you would reject the views of Calvin and Luther . . .

DOUTHAT: Absolutely.

COWEN: — that it’s strictly determined by God, but the Pelagian heresy that there is no original sin —

DOUTHAT: Right.

COWEN: — that also is unacceptable to you. That would lead you to Mormonism, or something else.

What makes that intermediate position so compelling to you? And is it in some way an underlying feature of how you think about politics?

DOUTHAT: [laughs]

I’ve never been asked that question.

[laughter]

DOUTHAT: I suppose that I’m drawn to the idea that the truth about human existence lies in what can seem like paradoxical formulations, and this is of course very Catholic in certain ways. Certainly a G. K. Chestertonian idea, so I’m just stealing it from other people. But the idea that various heresies of Christianity, Calvinism included — with apologies to my Calvinist friends — tend to take one particular element of you that’s supposed to be in synthesis and possibly in tension, and run with it. And therefore the truth about things lies in a place that may seem slightly contradictory.

And I think this is borne out in many ways in everyday experience. This both-and experience of human existence. The idea that you can’t split up grace and works in any kind of meaningful way. It’s connected to larger facts about the nature of human existence. The tension between determinism and free will that persists in any philosophical system. You can get rid of God and stop having these Jansenist Jesuit arguments about predestination and so on, but you’re still stuck with the free will–determinism debate. That debate doesn’t go away.

So, yeah, there’s a point at the intersection of different ideas that is as close to the truth as our limited minds can get and in Christian thought, we call that point orthodoxy. Now, how that is connected to my political views is a really good question.

I think that a lot of the time, in politics, I suppose, I am — in certain areas of our politics, I’m looking for that point, I guess you could say. But that’s mostly true in . . .

No, I guess it’s true in a lot of places. I think that the solution to . . . (maybe now we’re into more Hegelian territory rather than Christian territory), but there’s a solution to a lot of problems in some as-yet-uncertain synthesis. So I write a lot about social conservatism and abortion and feminism, and these kind of issues. And I do think that somewhere out there, in that zone of argument, there is a synthesis of the best social conservative ideas and the best feminist insights that I personally haven’t been able to grasp yet, and probably I’m not necessarily equipped to do so, and also that our society as a whole hasn’t grasped, but that that is where the actual truth lies. And you can distill it in certain slogan-ready ways, like saying, “Well, you need a more feminist pro-life movement,” or something like that. And those slogans only get you partway there.

But I do think that that idea of synthesis is somewhat important to the somewhat speculative political writing that I do.

COWEN: But, as you know, there’s a tendency within Catholicism to try to use Hegelian arguments to push a very liberal version of Catholicism. “Well, this thing is going to keep on evolving, there’s no end to the process” — so we can get away from your idea of Catholicism as spanning the generations — as something continuous and unified. Are you worried you’ll become too Hegelian, or are you not yet Hegelian enough?

DOUTHAT: I think the Hegelian insight can be true in the development of political forms and responses to problems that social changes create, problems that basic technological changes create, and you can hold that view while also holding the view that the Hegelian dialectic can’t be usefully applied to certain ideas and certain truths, and you can take extreme examples and say there isn’t a synthesis to be had with — to violate Godwin’s law early in our conversation — there isn’t a synthesis to be had with Nazi Germany. There are certain ideas about racial hierarchies and so on that are not part of some synthesis that you need to work through and grasp.

And then to be a Catholic, I think, is to believe that there is a larger body of revealed truths that have to remain as a grounding for civilization, Christian civilization, and so on, even as you grow forward towards programmatic, practical solutions and sociological solutions to new problems that emerge.

On the Old Testament

COWEN: We all know the Marcionite heresy: the view, from early Christianity, that the Old Testament should be abandoned. At times, even Paul seems to subscribe to what later was called the Marcionite heresy. Why is it a heresy? Why is it wrong?

DOUTHAT: It’s wrong because it takes the form . . . It’s wrong for any number of reasons, but in the context of the conversation we’re having, it’s wrong because it tries to basically take one of the things that Christianity is trying to hold in synthesis and run with it to the exclusion of everything else, and essentially to solve problems by cutting things away.

The Marcionite thesis is, basically, if you read the New Testament, Jesus offers you a portrait of God that seems different from the portrait of God offered in Deuteronomy; therefore, these things are in contradiction. Therefore, if you believe that Jesus’s portrait of God is correct, then the Deuteronomic portrait of God must be false; therefore, the God of the Old Testament must be a wicked demiurge, etc., etc. And the next thing you know, you’re ascribing to, again, a kind of . . . What is the Aryan Christianity of the Nazis, if not the Marcionite heresy given form in the 1930s and 1940s?

And so the orthodox Christian says, “No, any seeming tension between the Old Testament and the New, any seeming contradiction, is actually suggesting that we need to look for a kind of synthesis between them, and for a sense in which there is not contradiction, but fulfillment in some way, which —

COWEN: Bringing us back to Hegelian Douthat.

DOUTHAT: Yes, yes.

COWEN: Now to prepare for —

DOUTHAT: Right, no, no, and you’re absolutely right, there is a kind of . . . In order to get to the orthodoxy of Nicaea and Chalcedon, there is a sense in which there’s a kind of Hegelian fulfillment.

The issue there, though, is just that the orthodox Christian believes that at a certain point the revelation is actually final, that God essentially doesn’t play tricks on you. And this is I think an important idea — that too much Hegelianism leads you to the point where you’re saying, “Well, what God is saying in one era just doesn’t hold true in another.” And that gets you to a point where there’s a kind of a dishonesty, I think, necessarily imputed to God in that scenario, that he’s sort of withholding . . . He’s giving you a revelation, but he’s constantly withholding for the future, and I think the God that I would prefer to believe in does give . . . When he says he’s giving final answers, he actually means it.

On the New Testament

COWEN: To prepare for this conversation, I read some more Catholic theology. So I read Hans Urs von Balthasar, Karl Rahner, Yves Congar, Hans Küng, Edward Schillebeeckx —

DOUTHAT: You’re way ahead of me, then.

[laughter]

COWEN: — others. But let me give you my impression, and I hope this doesn’t offend anyone. It mostly really bored me.

[laughter]

COWEN: But, when I went back and reread parts of the Bible, the New Testament, it didn’t bore me at all. It was absolutely fascinating, gripping — wanted to go back and read it yet again. Now, given that theology comes through the church, is this not in some way evidence for a version of Protestantism being correct, or do you have a different reaction to these texts?

DOUTHAT: Is it all right to say that I have a similar reaction to many of them? Or will that —

I mean, that’s a dangerous thing to say, because, in my position as a sort of hack journalist who writes about Catholic controversies, I’m often getting criticized by professional theologians for lacking adequate theological training, and so forth, so if I admit that I find many theologians dense and boring, that will be used against me when my book comes out in a few months. But I guess it’s too late.

So, having said that — no, I think that the heart of Catholicism is found in the link between the New Testament and the form and structure and ordinary life of the church. And what theologians are doing is very important, but it is far from the most interesting and essential part of the Catholic project.

So, to the extent that there is an aha moment for someone thinking intellectually about the connection between the New Testament and the Catholic Church, it should come in the experience of looking at the Eucharist, looking at what goes on in Catholic churches every day around the world, and connecting that to the startling and shocking and scandalous things that Jesus says about his body and blood in the New Testament, connecting it to the form of the Last Supper, connecting it to that story.

And the theological commentary on all of this can be fascinating and theological controversies can be very interesting, but that, to me, the . . . Really, the heart of the connection between Catholicism as a religion and the startling, striking world of the New Testament lies more in liturgical life, the lives of the saints, the sort of everyday stuff of the Catholic Church rather than the abstract arguments.

I’ll also say that the post-’60s Catholic theologians are also maybe a little more dense [laughs] in certain ways. There’s a good piece by Rusty Reno, who’s the editor of First Things, that he wrote a little while ago, arguing that a lot of those Catholic theologians, the ones that you read, it sounds like they’re working as critics of a sort of existing Thomistic, Thomas Aquinas–rooted foundation in Catholic theology that they felt had gotten very stale and very boring. And they were right, I think, in certain ways.

But the problem is they’re also writing as if on the assumption that their reader understands this foundation that they’re operating in a landscape of critique and commentary and so on, that assumes a kind of 1880s or 1940s Catholic education in their readers. And so the collapse which they hastened in certain ways of that Thomistic consensus means that in certain ways their works don’t make that much sense, that they’re sort of driving forward, but there’s a missing synthesis that you need to sort of understand what they’re driving at sometimes.

But again, that’s a more theologically learned take than my own, which sometimes matches yours.

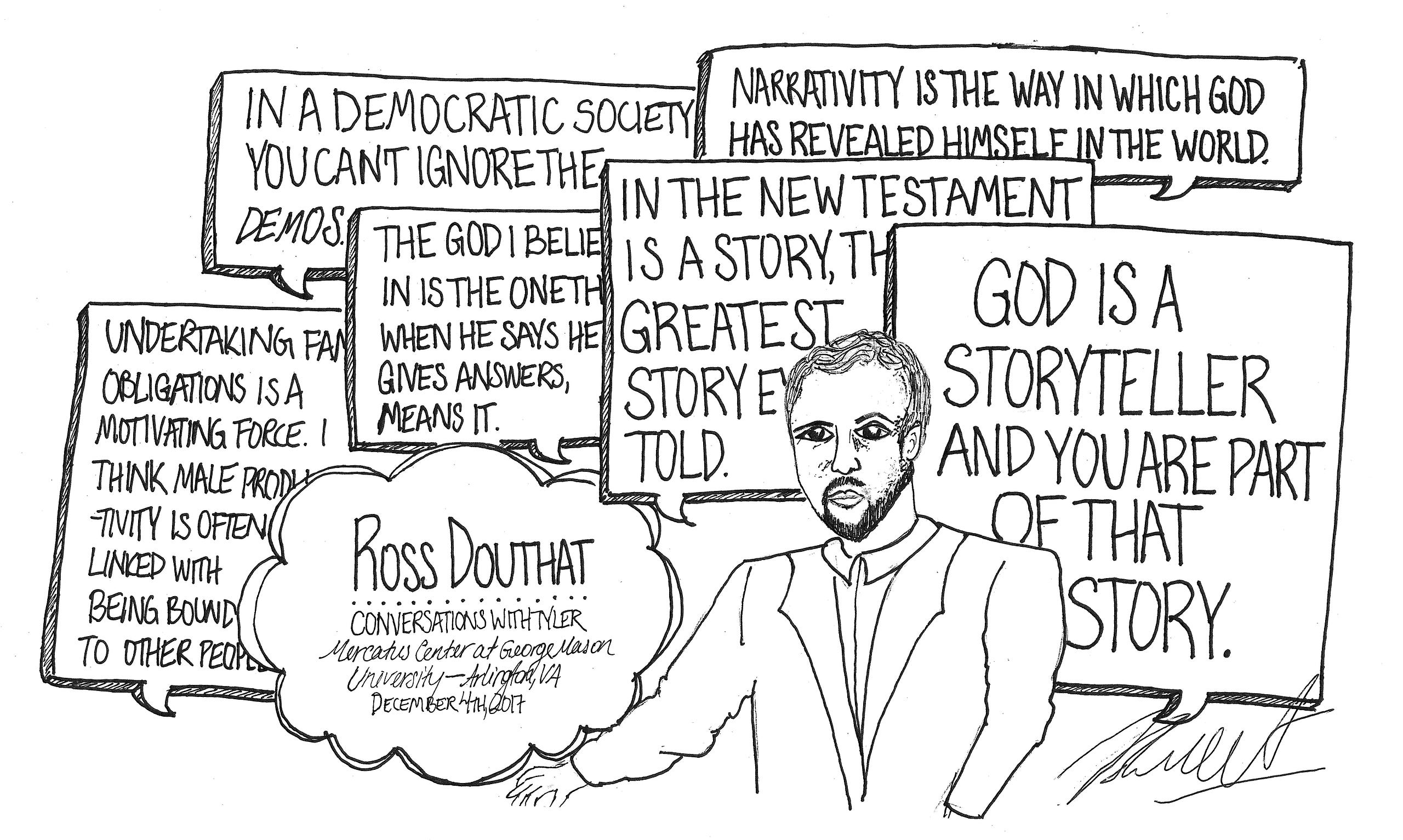

On theology through narrative

COWEN: Let me ask you my number-one question about you, and maybe it’s too big a question for you to answer, but it’s what I’ve been thinking about for the last few weeks.

The apparent — I wouldn’t say lack of interest in theology, but you don’t write about theology much in its theological aspects. Maybe a part of the sociological narrative. But what strikes me rereading everything you’ve written as a whole is how interested you are —

DOUTHAT: [laughs] God help you, man.

COWEN: — in aesthetics, in narrative, film, television, and novels — that this is elevated.

So if you read St. Augustine, as you know, in the Confessions, he’s very skeptical about theater. It’s potentially a form of idolatry; it distracts people from God. And theology is weaker in your approach and narrative and aesthetics are stronger. And this strikes me ultimately as a kind of theological decision. So in the Catholicism of you, what’s the theological basis of narrative and aesthetic themselves being elevated over theology? That’s what’s been bugging me.

DOUTHAT: OK.

COWEN: And maybe if you could address that, I would be happy.

DOUTHAT: I’ll venture a theory, again, about something that I haven’t thought about before you raised it 30 seconds ago. So please take this with a grain of salt.

I think that you could make the argument that narrativity is the way in which God has revealed himself in the world from a Christian perspective, from a Judeo-Christian perspective. You know the Old and New Testaments contain a lot of theologizing, but they are, above all, narratives. They are stories of a chosen people. They are travails and betrayals and wars, and miseries, and judgments, and all the rest. And then there’s a story in the New Testament that is, as the cliché goes, the greatest story ever told. And I mean I think you’re right about me — when I read the New Testament, I want to read the gospels much more than I want to read St. Paul. And I find the gospels much more interesting than St. Paul, and that’s obviously not true of everybody, or we wouldn’t have been having wars about what Paul meant in Christianity [laughs] for the last 2,000 years.

But I think to the extent that I would defend my own instincts and my own approach — sometimes I say this to my children when I’m clumsily trying to indoctrinate them in my faith; I say “you are living inside a story, and God is the storyteller.” And again, this is not a thought original to me at all, but God is the storyteller and you are an actor within that story. And the difference is that in this story, God, Christians would say, God himself enters the story: he becomes a character in the play, which is a very difficult thing for a playwright to normally do.

But that story, the fact that God is a storyteller, tells us something reasonable about how best to approach him and that it is not just OK, but completely plausible to approach him through narrative, through poetry, through art, through stories, and so on. And there is a sense — I think this idea I’m stealing from Alan Jacobs, who wrote a biography of C. S. Lewis — but I think there’s a real sense in which — and maybe this speaks to the failure of Western theology over the last 50 years — but Christians in the West, in the United States — well-educated, would-be intellectual Christians — tend to be heavily influenced by storytellers, heavily influenced by Lewis, heavily influenced by J. R. R. Tolkien, heavily influenced even by Dorothy Sayers and her detective stories, heavily influenced by Chesterton’s Father Brown stories.

I think it’s probably fair to say that Chesterton’s Father Brown stories had as much influence on my worldview as his more sort of polemical and argumentative writings. And, again, I think therein lies some important insight that I haven’t thought through, but I think you’re correctly gesturing at, about a particular way of thinking about God and theology that isn’t unique to Christianity, but that is strongly suggested by just the structure of the revelation that we have. Marilynne Robinson has a line, I think in Gilead, about — one of the characters is imagining that this life is like the epic of heaven. That we’re living in the Iliad or the Odyssey of heaven. This is the story that will be told in the streets.

And I think that’s a very powerful and resonant and interesting way of thinking about our lives, but thinking about the Christian view of history that we’re living inside a very, very interesting story that people will be talking about in heaven for a long time.

On tension between Eurocentrism and Catholicism

COWEN: Now you’ve been very critical of Angela Merkel’s decision to take in so many Syrian refugees into Germany, the heart of Europe. And of course many of those refugees are Muslims. So when I read some of what you write, I sense a kind of tension between Catholicism, which is universal in some important ways, but also a kind of Eurocentrism and a fear that the longstanding historical connection between Catholicism, Christianity, and Europe will be broken by migration patterns, by changes in the European Union.

So, at the margin, how much tension do you see between a kind of Eurocentrism that’s in most of our thinking in the West, and Catholicism itself?

DOUTHAT: There’s some substantial tension, I think.

I think that the situation in Europe is a very challenging one for anyone to think through, but particularly for a Catholic, because you have this sort of — it’s the ancestral homeland of my faith. And we’re talking about stories: the story of Catholicism is a European story for much of its history. Much of the great dramas, the great debates, and so on take place in that continent. And when I sort of think . . . When I think of figures that I identify with, when I think of sort of the writers and artists and so on that I relate to, they are primarily European just because of that synchronicity. Because the faith is Europe, and Europe is the faith, historically.

But now we’re in an era when that’s not really true. Europe is sort of a museum of Catholicism in this weird way. With some exceptions, but particularly in Western Europe, it’s a museum. And the culture of Europe is in certain ways hostile and becoming increasingly hostile to traditional religious faith. And at the same time, you have this sort of alternative of Islam whose potential power and potential ability to reshape Europe is sort of ambiguous. It’s not at all clear to me how powerful or how substantial that influence would be.

And so the Catholic is sort of given, at least at the moment, this sort of strange choice. Would you rather have this museum of your faith be preserved in its existing form in a sort of post-Catholic, maybe still residually Catholic situation, or would you have it be changed dramatically by the entrance into Europe of the faith that Catholicism contended with for world mastery for hundreds and thousands of years?

That’s a strange choice to be placed to someone, I think. And it’s further complicated by the fact that sort of overshadowing that particular tension is the reality that a large share of the potential long-term migration to Europe could be from Catholic and evangelical portions of Africa. It sort of adds a further layer of dilemma.

And so my reaction to Merkel’s move — it sits at one remove from that debate. My reaction to Merkel’s move was very much as sort of a political analyst who thinks to myself, stability is better than chaos. As flawed as the liberal order is in various ways, I want it to hold up. Therefore I don’t want leaders to make these big, dramatic moves that I think could have an obviously destabilizing impact.

So I’ve been skeptical for a long time of the sort of extreme sort of Mark Steyn or beyond–Mark Steyn analysis that Europe is inevitably going to go Muslim and so on. But having Merkel make a decision like she did sort of pushes me slightly in a Steynian direction, probably. It makes me think Europe’s elites are not reckoning with how big, how fast demographic transformations can change societies, divide societies, create space for all kinds of extremisms to flourish. That’s sort of my columnist’s pundit answer.

But I don’t know exactly how to connect it to this deeper question of what kind of future of Europe, given the available options, should a Catholic desire. Because to some extent, if you’re asking me would I rather Europe be atheistic and sort of effectively anti-Catholic for the next 1,000 years, or rather have it be Muslim — perhaps I’d rather have it be Muslim, right? From a Catholic perspective, a sincere Islamic faith is preferable to a truly post-Catholic landscape. But at the same time, we’re not being fully presented with that choice, either. So, anyway, I’m just suggesting various uncertainties, I guess.

COWEN: Your forthcoming book is an estimate that perhaps by 2040 there will be 460 million African Catholics, twice as many as in Europe. Arguably they go to mass much more often. So if you imagine a future Catholicism where the letter of James is more central to the Bible, there’s more exorcism, more fasting, holy water is more important, there’s a more magical view of the Eucharist, arguably a kind of supernaturalism is more primary, would your reaction just be, “Well, my loyalty is to the church, so I’m just going to go with that flow,” or do you feel there’s some more Eurocentric view of Catholicism that’s being lost in a way we would want to fight for?

DOUTHAT: Both. I would think that the future of an African Catholicism, of a sort of Africanized Catholicism, is better than many, many futures that I can imagine, but I would still be sorrowful if particularly European distinctives within the church are lost in that transformation.

I think if I were playing the optimist, I would say that there is a Euro-African future for the church where African forces, African migration, African ideas, African leaders help renew and enrich and return European Catholics to their faith. And you can find small, strange examples of this. Like Robert Sarah, who is this Guinean cardinal who is seen as a partial antagonist to Pope Francis in certain intra-Catholic debates. He went to the Vendée in France for the anniversary of the Vendée and gave a speech there hailing the resistance of Catholics to the revolutionary regime in France in the 18th century, which is kind of this extraordinary moment, not anything you would have imagined 150 years or 200 years ago. And a kind of moment that, yeah, lets you briefly imagine that kind of — that there could be a Catholicism that revived certain European elements in the process of becoming more African.

But that’s a very, from a Catholic perspective, optimistic view, and the likelihood is that things will be more chaotic and messier and so on. But ultimately my first loyalty is or tries to be to the church rather than to European culture, so I would certainly take an African Catholicism over the museum that we have in Europe today.

On the merits of Islam

COWEN: When you see how much behavior Islam or some forms of Islam motivate, do you envy it? Do you think, “Well, gee, what is it that they have that we don’t? What do we need to learn from them?” What’s your gut emotional reaction?

DOUTHAT: I think that Western civilization is decadent, and that decadence has virtues — among them, the absence of the kind of massive bloody civil wars currently roiling the Middle East. But, at the same time, there is a sense in which, yeah, there are parts of Islam that are closer to asking the most important questions about existence than a lot of people are in the West. And asking important questions carries major risks and incites levels of extremism that we’ve tamped down and put away, but that desire for the extreme and the absolute and the truth about things that animates some of the best and some of the worst parts of Islam, I think it’s better for human beings to have that desire than not.

COWEN: There was once a long blog post you wrote really in response to me —

DOUTHAT: Yes. [laughs]

COWEN: — and in that, subject to various conditions too complicated to explain (but I’ll mention them so you’re not misquoted), you at least mentioned the possibility of a 10 percent chance that there’s some truth to a synthesis of Judaic, Christian, and Muslim ideas. In that synthesis, highly conditional within your discourse, what’s the element from Islam that appeals to you?

DOUTHAT: That’s a good question.

I think for the synthesis, I guess when I think about the synthesis in that case, I gave it quite a low probability because it seems to me that Judaism and Christianity make — and, again, this comes back to the storytelling issue maybe — but I think there’s a more organic and obvious unity in that story than there is in the combined story. So I think for the . . .

I don’t think I have a certain answer; I can tell you things — as I just, I suppose, started to — that I admire within the Muslim world. But I can’t tell you definitely, and this is I guess why I am a Christian and not a Muslim. I can’t tell you what I think — how I think that story would fit together. If God’s revelation to Muhammad were as definitive a revelation as the revelations of Christianity and Judaism, I can’t make that story work; so the story then has to be bigger. I guess that for there to be a Judeo-Christian-Islamic synthesis, then it does await some further revelation that would make more sense of the Islamic story to me.

On Opus Dei

COWEN: As you know I come at all of this as very much an outsider, so let me ask a very naive question.

If I look at the Catholic Church, there’s a movement, as you know, called Opus Dei. The priests of that movement, they seem to be less caught up in sex scandals. Parts of the movement seem to have some understanding of what you might broadly call conservative economics. In Spanish politics in the ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s they were actually considered a liberalizing force, so they don’t have to be seen as reactionary per se.

Why aren’t they simply the good guys? They don’t come up much in your writings. I’m reading you and I think, “Where’s Opus Dei?”

DOUTHAT: I mean, I’m pro–Opus Dei overall. I think that my only . . . It seems to me sometimes that Opus Dei is a particular apostolate, right, and the particular idea of Opus Dei is that it’s not primarily supposed to be a priestly order, even though there are of course priests of Opus Dei.

The central idea, and with apologies to Opus Dei members if I’m getting this at all wrong, but the central idea is that it’s a ministry. It’s an apostolate for laypeople who are at work in the business world, the journalism world, the corporate world, the communications world, and so on. And as such, I think it has an admirable and important vocation in the life of the world and the life of the church. But it seems to me in part that there is a sort of . . . There’s a kind of, not set-apartness exactly, but there’s an element of . . .

Well, I think a big part of the crisis in Catholicism in the last 60 or 70 years can simply be distilled to a collapse in the sense of the importance of religious life, of consecrated life, of the priesthood, religious orders, sisters and brothers, and so on. And it’s as easy for me to say because I did not become a priest and so it’s always easier once you haven’t become a priest to say, “Oh, well, you need more people to become priests.” But to the extent that that’s true, Opus Dei seems like it’s very well tailored in certain ways to secular society as it exists right now.

But I think the ultimate revival of the church is likely to come from a slightly more radical view of the proper relation to the world — that essentially what the church needs now is the equivalent of the Franciscans, the Dominicans, the Jesuits, these kind of orders from previous eras that are sort of . . . I mean, Opus Dei asks laypeople to take vows of various kinds; celibate laypeople are part of the Opus Dei structure. And I think that there is . . . Essentially, there is just a straightforward need for a more old-fashioned model of just priests and nuns. The church needs more priests and nuns. Catholicism can’t function without priests and nuns, which doesn’t take anything away from what Opus Dei is doing and, of course, they have many vocations and many priests.

But yeah, to the extent that it doesn’t get the due maybe that it deserves in my writings, that’s probably, maybe, the root of it. Again, you’re teasing out things I haven’t even begun to think about before, which is . . .

There’s no particular reason why. The sacramental life of the church depends on a strong priesthood, depends on men becoming priests; it depends on religious orders and so on. And so full revival in the church would need a priestly center to it, in a way, and not just a focus on sort of apostolates and evangelization within the world. Catholicism has been caught up in the idea that this is the Age of the Laity for the last 50 or 60 years. I think the Age of the Laity has kind of been a disaster for the church in certain ways.

On conservatism with religion

COWEN: Here’s a question from a reader, and I’m stringing together a few different sentences — something like, “Is conservatism always particularist and local? Can there ever be a universalist conservative position? Is the phrase ‘Christian conservative’ an oxymoron, because Christianity (like Islam) is a universalist faith that seeks to convert every soul on earth? Isn’t the word ‘conservative’ better suited for more aloof, inegalitarian, less-aggressive religions, such as Hinduism, which are less insistent on ‘natural right’?”

How would you respond to that?

DOUTHAT: I think conservatism is particularist, sort of by the definition, yes. And I think that every form of conservatism is going to be different depending on the cultural context. I think conservatism in America at its best is trying to preserve a kind of American exceptionalism that doesn’t sort of have applications really when you’re thinking about what a German conservatism would be, or a Russian conservatism, and so on.

And, in that sense, Christianity can only be conservative in sort of provisional and context-bound ways, right? In a culture that was universally Christian and is in the process of ceasing to be so, then Christianity — then the phrase “conservative Christian” makes a lot of sense, in the sense that you have a universal faith that has taken over a particular piece of the world, and you’re trying to sort of preserve its influence and power over that piece. But that’s always contingent and temporary. And, yes, Christianity is at its root a more radical religion.

On Watership Down

COWEN: Now we have two porcelain bunnies here on the table with us, and those are to refer to a novel, Watership Down, that you once called “the best modern novel about politics.” Why is this the case?

DOUTHAT: That was maybe an overstatement —

[laughter]

DOUTHAT: — but I think Watership Down . . . We live in an age of intense attention paid to children’s books and young adults books by people who are adults, and there’s a lot of reasonable controversy over whether that’s a good thing necessarily, but I’ve been always disappointed that there hasn’t been a kind of sustained Watership Down revival because it’s such a great book and it’s a book about — essentially, it’s about a founding.

It’s connected, in a sense, to the kind of things that the Straussians are always arguing about and so on. What does the founding mean, and so on? But you have a group of rabbits who go forth and encounter different models of political order, different ways of relating to humankind, that shadow over rabbit-kind at any point.

You have a warren that has essentially surrendered itself to humanity and exists as a kind of breeding farm, and you have a warren that’s run as a fascist dictatorship essentially. And then you have this attempt to form a political community that is somewhere in between the two, getting back to the Hegelian synthesis and so on. And you have sort of this primal narrative where the problem is of course that they don’t have any females, and so there’s this competition, this competition for reproductive power that’s carried out between these different warrens where the rabbits from the good warren have to literally — not kidnap, because the does come willingly — but steal women from the fascist dictatorship, which maintains a ruthless control over reproduction.

So there’s just a lot of fascinating stuff there, and then it’s all interspersed with storytelling. There’s the sort of rabbit folktales that Richard —

COWEN: So, narrative again.

DOUTHAT: Narrative again.

— that Richard Adams came up with, that are just brilliant, about El-ahrairah, the great rabbit folk hero, and his relationship. There is actually the rudiments of a rabbit theology in Watership Down.

COWEN: What kind of theology is it?

DOUTHAT: How would rabbits think about God? How would rabbits think about their proper relationship to God? What kind of myths would they develop to explain their position in the world as opposed to every other creature? And it’s all quite brilliant. It’s a great novel. In fact, I reread it last year, and it was still quite great.

And then there’s even, right, there’s even a mystical element. The book begins with this rabbit Fiver, who is sort of a runt, who has visions — and the whole founding is based on various prophecies and visions that he has throughout the beginnings of this rabbit warren, that these rabbits go out and found. So he has a vision of apocalypse, so there’s an Aeneid element, clearly, where — probably he uses quotes from the Aeneid; he has quotes before every chapter — where the city falls and you have to go found a new city and there’s religious visions along the way that relate to the legitimacy of the founding.

And there’s a tension between . . . Sorry, I’m rambling, but you got me going here. There’s this great tension between Hazel and Bigwig, who are the two leaders of the city that’s being founded, and Bigwig is — he was a member of the Owsla, which is the rabbit martial order. And everyone assumes when they meet this group of rabbits that he is the leader, but in fact the leader is Hazel, who is this rabbit who is neither the visionary nor the military leader, but just — he’s the politician, and he’s good at it, and the success of the warren is based on ultimately the subordination of Bigwig, and the martial, and the religious to the politicians.

So the next time you have Peter Thiel here for one of these conversations, you can really press him on if there’s a Girardian element in Watership Down. There’s a lot further to go with this, but I’ve probably gone far enough.

[laughter]

The next time you have Peter Thiel here for one of these conversations, you can really press him on if there’s a Girardian element in Watership Down.

On cats

COWEN: Your wife, Abigail Tucker, has published a famous book about cats. What’s the biggest disagreement you have with her about cats?

[laughter]

DOUTHAT: Well, I need to be a little careful here, because . . . Abby, when we met and got married, loved cats; and I always sort of admired cats from a —

I was a cat person who admired their singular standoffishness, and so on. I think in certain ways writing the book about cats brought her around to something closer to my view.

She started the book shortly after we started having children and one of the interesting things that she realized was how much of her reaction to cats was a displaced child reaction; that cats have these faces that look like infants’ faces and have the eyes and the wide faces, and they meow in this way that approximates an infant’s cry, and they essentially hijack the maternal instinct. So she had sort of maternal feelings towards cats, but in the process of having actual children and writing the book, I think she came to an appreciation of them more as these fascinating apex predators. That’s sort the theme of the book, which you should all read. It’s much more interesting than late 20th-century Catholic theology.

[laughter]

DOUTHAT: But the theme of the book is this idea that this sort of cuddly fur-baby in your room is an apex predator who has taken over the world through its relationship to human beings. And I think that was my view all along.

[laughter]

DOUTHAT: So really we’ve sort of smoothed out our fundamental disagreement by the process of having her learn more about cats than anyone could ever possibly imagine knowing.

On things under- and overrated

COWEN: As you may know, we often in the middle have the segment “Overrated versus Underrated” —

DOUTHAT: Been dreading it, yes.

COWEN: — and, of course, feel free to pass.

Let’s start with the TV show The Sopranos. Overrated or underrated?

DOUTHAT: Very slightly underrated.

COWEN: Why?

DOUTHAT: I think that the proliferation of Sopranos imitators and the desire of certain people to . . . There are a lot of people who wanted to like The Wire more than The Sopranos because The Wire was sort of sociological and political in a way that Sopranos wasn’t. And so there was a certain number of people who should have known better who convinced themselves that The Wire was a better show than The Sopranos, which it is not —

COWEN: But Sopranos is more theological, right?

DOUTHAT: The Sopranos is more . . . Yes.

And it’s more personal and psychological. I mean it is . . . The characters on The Wire are fascinating, but they are . . . When you meet them you know who they are. It is Dickensian in that sense; the sort of endless jokes about the Dickensian element on The Wire are right. And Dickens is a great novelist and The Wire is a great show, but there’s a depth to much of The Sopranos that I think is not equaled by The Wire and hasn’t quite been equaled in any show since. So —

But only very — people love The Wire, so it can only be very slightly underrated — I mean people love The Sopranos.

The Wire is a great show, but there’s a depth to much of The Sopranos that I think is not equaled by The Wire and hasn’t quite been equaled in any show since.

COWEN: Evelyn Waugh — Brideshead Revisited, a novel.

DOUTHAT: Overrated.

COWEN: Why?

DOUTHAT: There is a little too much sentimentality in the Catholicism. And the Sword of Honor Trilogy is a little more cold-eyed and therefore slightly better.

COWEN: A side question: If you think about a lot of the Catholic authors — Walker Percy, Graham Greene, Flannery O’Connor, Gene Wolfe, Louise Erdrich — do you feel as a whole Catholicism is sufficiently well represented in literature, or in a sense are you a bit let down by the aggregate weight of the better-known Catholic novels?

DOUTHAT: No. I think it’s well represented, and I think that the decline in Catholicism’s importance in literature since that Waugh-Greene golden age has happened in parallel with the decline of literature’s cultural importance in certain ways. Some of it depends on whether you claim Shakespeare for the Catholics or not, which is a —

COWEN: Do you?

DOUTHAT: — a lively . . . [laughs] It’s been a while since I . . .

COWEN: You want to, right? You want to.

DOUTHAT: It’s been a while — I want to, yeah. [laughs] It’s been a while since I really dug into that debate, but I’d like to. And I think that actually does, in a weird way, tip things in certain ways when you’re talking about the scale of things.

But no, the period that produced Waugh and Greene and a lot of those writers is in certain ways one of my favorite periods in modern literature. And even the writers in that era who are not practicing Catholics seem to me to be influenced in different ways, like Hemingway and Fitzgerald in different ways. For instance, Hemingway is writing in a Catholic cultural context in a lot of his stories and Fitzgerald is, of course, a lapsed Catholic of a certain kind. So I think Catholicism hangs in an interesting way over that whole first-half-of-the-20th-century period of literature. And I think that’s the best recent period of literature, so I’ll claim some chauvinistic pride.

COWEN: Elgar’s oratorio, Dream of Gerontius?

DOUTHAT: Pass.

COWEN: What music then best expresses God?

DOUTHAT: In musical terms, I’m a bit of a philistine. I like a lot of . . . Well, this is — again, you’re going to get me on narrative every time. I like a lot of folk, country kind of music. I don’t know that I would make any special theological claims for it, generally. But that’s sort of my musical tastes run to . . . I don’t even know how to say this without being embarrassing, but like Natalie Merchant, that kind of thing. And I haven’t thought through the theological dimension, except I do like some of the stories, the storytelling, in country music.

COWEN: The Andrew Lloyd Webber musical Jesus Christ Superstar.

DOUTHAT: [laughs] It’s been a while, but I’ll say slightly underrated, just for kicks.

On Dante’s Inferno, the next Great Awakening, and Sam’s Club Republicans

COWEN: What should we infer from the narrative superiority of Dante’s Inferno within the Divine Comedy — but of course feel free to challenge the premise.

DOUTHAT: No, I won’t challenge the premise. I think that there is a sort of sincere limit to human imagination when it comes to contemplating the idea of the beatific vision and so on, and that comes across. We don’t know how to tell stories about the story outside our story in quite the same way. And the Inferno is telling a story about the world that we’re all familiar with and that’s easier.

COWEN: Which American demographic will start the next Great Awakening?

DOUTHAT: Most . . . Let’s say Asians, just to be provocative.

[laughter]

COWEN: OK. Good answer.

DOUTHAT: And if you ask me which Asians, I’ll really, I’ll . . . No.

[laughter]

COWEN: In your book with our common friend Reihan Salam, you develop a philosophy sometimes called the Reformicons, and you make the point that Republicans ought to try harder to address what are sometimes called Sam’s Club Republicans — lower-income groups who have been hurting in some ways due to economic trends. When you look at the last year to year and a half or two years of our politics, does part of you want to turn back and have politics more focused on elites once again, and does any part of you feel that trying to address Sam’s Club Republicans, Democrats, Independents, that there’s a danger there that we hadn’t seen before, or no?

DOUTHAT: No. I think that you can’t escape — in a democratic society, you can’t escape the demos. And so attempts to maintain elite control over politics that don’t address deep, profound, systemic social problems are doomed to eventually produce, excuse me, things like the Trump phenomenon.

And, of course in sort of a narrow, moment-by-moment way during the campaign, if you followed my mostly wrong commentary during Trump’s march to the nomination, I was all for sort of elite energy being expended in that moment to block Trump. And the point of elites is to prevent manifestly unfit people from becoming president.

But, if there is a larger systemic elite failure, then things like that will happen. And so the way to avoid that situation is for elites to focus — again, to care about what’s going on with the demos. With the actual people out in actual America. And that’s something I don’t think Republicans were very good at before Trump, and I don’t think it’s something they’re particularly good at under Trump. But, I think, had they been better at it, the Trump phenomenon would at least have been different than it was.

COWEN: CRISPR is a new technology that has made significant progress lately. Maybe it will never allow us to deliberately engineer the entire human or the entire human baby, but it seems plausible to believe it could lead to some kind of slow genetic drift, in a way that would be in some manner planned or programmed by human beings. For you, is this a kind of nightmare, or does this possibly have an upside or even a utopian side?

DOUTHAT: I’m skeptical of its utopian side. I don’t think it has to be a nightmare, but I think that there has to be . . . I think that there is a deep aversion, particularly in the United States but elsewhere as well, to exercising political control over technologies. And I think the challenge of the next 100 to 500 years of human history is getting better at exerting political control over technologies and preventing actual nightmare scenarios. And I feel this in certain ways with computers, the internet, virtual reality, and so on.

I think that we’re — that to me is a more immediate source of anxiety than genetic engineering. I think that we’re going to wake up in 20 or 30 years and be — well, we may not wake up, but I would like to think that we’ll wake up in 20 or 30 years and say — “Why were we putting all of our children in front of these screens for so much of their childhood and shouldn’t this be something that we had exerted actual control over instead of just leaving it to some combination of experiment and market forces and governments wanting to be hip and cool and buying a lot of Chromebooks that Microsoft wanted to unload,” and so on.

And so I could see something similar happening with genetic technology, but I think bringing technology under control so that the more radical genetic experiments are limited and happening in, happening at the margins, basically, that should be the goal. I think it doesn’t mean that we could actually succeed, but I think it’s a reasonable goal to set.

COWEN: What do you think we’ll see as the main cost 30 years from now from letting our children sit behind screens for so many hours a day?

DOUTHAT: I think it’s bad for human imagination, for normal relationships, for appreciating reality as it actually exists. I think the reason we may not see costs is that it has a numbing effect in certain ways on human behavior. That it doesn’t necessarily lead to egregious acting out of the kind that leads to crime waves or political tumult or anything like that. So the costs — I think the costs are likely to be felt in, as I think they’re already to some extent being felt in, increased mental disturbance on the margins, difficulty forming marriages, families, normal human relationships, and more cultural despair, I think.

COWEN: As you know, euthanasia is now relatively easy in both the Netherlands and Switzerland. What do you feel is the intellectual and/or moral error behind this reality? And I take it you do view this as an error.

DOUTHAT: Yes. I do. I think that it’s, that it is a, it’s an example, I suppose, of — to go back to the very beginning of our conversation — of where this sort of liberal view of rights has so far escaped its Christian origins as to become a vision of self-ownership that I think is not actually true to human existence, true to human experience. And yeah, I think that the case against suicide is quite similar to the case against murder. And I think our drift away from recognizing that as a case study in the working out of certain liberal ideas that have gotten far enough from the truth as to just be false.

On being open to weird ideas

COWEN: Religion aside, learning to tie your shoelaces aside, what did you learn from your mother?

DOUTHAT: [laughs] I suppose I learned . . .

This folds in religion, so I apologize; it’s cheating a little bit. But we spent a lot of time . . . My mother had health issues when I was young, and we ended up as religious as we were in part because of healing services that she went to because she was ill or because she had friends who recommended them.

But there was a wider orbit to that where we ate health food long before health food was cool. We ate tofu, and you could only get tofu by going to the back of a weird health-food store, and it would be in these vats of water, and you’d pick up these huge blocks of tofu with tongs, like people pulling icebergs out of 19th century ponds in Vermont. And so I would say that between the religious element and the strange world of health food . . . You’d go to a health-food store and you’d have the health-food restaurant here, and you’d have the New Age bookstore next to it — they’d always be attached — and you would always have the same books. You’d have the Utne Reader and all those kinds of magazines.

But at the same time I was having in certain ways a conventional upper-middle-class, southern-Connecticut background. And I think I had that weird combination of normalcy in certain ways, religious experiments over here, dietary experiments that blended into weird cultural experiments over there. It gave me generally an appreciation for the weird diversity of America, that I think I wouldn’t have gotten if my mother hadn’t been ill and sought out strange cures and so on. And it also gave me an appreciation for the fact that there can be things that are true about the universe that are not available through the experience of expert consensus and so on.

We were very much outside the mainstream during my childhood. And the fact that there was a lot of lies and nonsense and BS outside the mainstream, but there were also things that I’ve held onto and think were true, that’s had a fairly powerful effect on my thinking.

We were very much outside the mainstream during my childhood. And the fact that there was a lot of lies and nonsense and BS outside the mainstream, but there were also things that I’ve held onto and think were true, that’s had a fairly powerful effect on my thinking.

Not always — like with the anti-vaccine debates, for instance. The anti-vaccine side seems to me to be pretty much just wrong and obviously dangerous in certain ways and so on. But there is always a small part of my mind and experience that wants to stick up for the anti-vaccine side, which I don’t do in the pages of the New York Times because there is no compelling argument I can see, and it does a disservice to millions of children to make an argument that people shouldn’t vaccinate their kids. That’s all true, and well, and good. But something like the anti-vaccine crusade will be proven correct. There are weird ideas out there right now that are actually true. And I think the strangeness of my childhood, that’s something that I carry with me as an assumption.

COWEN: Three more quick questions before I turn it over to all of your questions.

How people pronounce your last name: What does it tell you about their class backgrounds or otherwise?

[laughter]

DOUTHAT: There are two main ways to mispronounce Douthat. The first is to say “Do that.” [laughs] And the second one is to say “Du tá.” And, essentially, as you climb the pretension ladder in America, the “Du tá” mispronunciation becomes more prevalent, whereas when I was in middle school in fourth grade the “Do that” mispronunciation was more prevalent. But you can always tell whether someone’s gone to graduate school or not by whether they try and mispronounce it as a French last name.

COWEN: You wrote a New York Times column yesterday on sterility, and you cite three different individuals as wondering that maybe sex will be too much pushed out of American life. One was Masha Gessen, who of course is from former Soviet Union; Cathy Young, who grew up in Moscow; and Geraldo Rivera, who actually is half-Jewish-Russian. So all three of the people you cited, whether you’re aware of it or not —

DOUTHAT: Did not think of that, yeah.

COWEN: — are Russian, and they’re the ones worrying. What do you infer from this?

[laughter]

DOUTHAT: That Russia is a very cold country. [laughs] No.

I do think there is absolutely no question that people who have lived experience of totalitarianism, which I do not, thankfully, tend to fear anything that smacks of totalitarian impulses, and so to the extent that there’s . . . I’m not sure about the Geraldo case, but… [laughs] His seemed more like a self-justification for a life badly lived, but to the extent that there is actually something there, then, yeah, I think it’s a normal reaction to being traumatized by authoritarianism.

On the Ross Douthat production function

COWEN: Last question, and this is also a perennial.

You became famous at a very young age; you’ve published four books; youngest New York Times op-ed columnist ever. The last two years you’ve even had health problems; you’ve continued to be, as far as I can tell, as productive as ever. What is the Ross Douthat production function? What is your productivity secret that maybe is undervalued by other people?

There’s plenty that goes into what you produce, but what would be an insight you would share with us as to how you get this all done?

DOUTHAT: [laughs] Undertaking family obligations certainly helps, as a motivating force. I think that male productivity is — I don’t want to say this isn’t true of female productivity too, but I only have the male experience to go by — I think male productivity is often . . . It’s often closely linked to being bound to and linked to other people, and having kids and a family and so on. I think that that’s a not uncommon root of greater productivity. And I’m certain it’s true in my own case. I wasn’t married that young, but I was married younger than many people in my cohort.

And, I don’t know, you also . . . I mean, journalism, you go to events with wonderful hosts and audiences and so on and people sometimes introduce you as a public intellectual. Sometimes they even say “thought leader,” and that’s the worst.

[laughter]

DOUTHAT: When I run my totalitarian state . . . No.

But journalism is a trade, right? I mean there is obviously an intellectual component. And we wouldn’t have been able to sit here and have this conversation with me babbling at you if I didn’t have intellectual pretensions. But the work of journalism — this is less true in the age of the internet — but it is linked to a very physical thing that comes out every week, or every month, or every day, and it comes out and it has to be filled.

There is a place on the New York Times, on the printed New York Times, that would be blank or have an ad stuck on it if I didn’t write my column. And so you write the column. You write the column. And it’s useful for journalists to think about it this way — it’s useful for anyone inclined to over-romanticize or over-admire journalists to think about it this way.

But there is a sense in which writing a column is — it’s like you’re a plumber. The toilet has to be fixed, so you fix the toilet. The column has to be written, so you write the column. And getting lost . . . There’s another version of myself that was going to write novels —

COWEN: Fantasy novels.

DOUTHAT: Fantasy novels — that was going to follow these aesthetic and narrative ambitions, that you rightly discern lurking below the surface of my analysis of the Republican tax plan, or whatever. And maybe that version of myself would have produced the great American novel, some great work.

Certainly I like to imagine that — or at least something that sold as well as George R. R. Martin. But it also might be the case that if I had spent my life sitting around with my unfinished novels, I never would have produced anything interesting. And so it’s better to be a tradesman, and that’s at least part of how I think about my job.

COWEN: We will get to your questions in a moment, but Ross, thank you very much.

[applause]

There’s another version of myself that was going to write novels…but it also might be the case that if I had spent my life sitting around with my unfinished novels, I never would have produced anything interesting. And so it’s better to be a tradesman, and that’s at least part of how I think about my job.

Q&A

AUDIENCE MEMBER: I was wondering how you thought the development of artificial wombs will change the politics of the abortion debate.

[laughter]

COWEN: A softball.

DOUTHAT: Well, it’ll be interesting if we do actually develop artificial wombs, which I’m not 100 percent sure that we will. But supposing that we do, my expectation would be that it would be . . . It would create a weird cultural crisis for the kind of people who currently are pro-life, while also creating substantial political pressure in favor of the pro-life cause. And I’m not entirely sure how those two things would interact with one another.

But you would clearly have a sort of deep religious resistance to the technology, to the practice, to that sort of severing, and you would have strong cultural resistance to it independent of religion. I think there would be a strong anti-artificial-womb . . . As in the crunchy bookstores of my childhood, there would be a left-wing, hippyish resistance to it as well. The question would be, How would that resistance to it interact with this possibility that here you have a technocratic solution to the abortion debate?

But I’ll say I’m a little skeptical that, if you imagine . . . Again, it depends; how do you get to the artificial womb point? Is it something where — are you imagining a world where a woman gets pregnant and somehow the embryo is removed from her body and placed into the womb? That seems . . . requiring a level of technological intervention that would raise a host of the same privacy concerns and so on that motivate certain portions of the pro-choice side. Or are you envisioning a world where you have artificial wombs and everyone is provisionally sterilized at age 14? This becomes the state policy, and so on? So you could imagine a pro-life totalitarianism that emerged out of some combination of technologies.

All of which is to say I don’t have a brilliant answer for your question, but I think there would be a lot of very strange and different cross currents that the people most inclined to make the pro-life argument right now would be disinclined to immediately run with whatever political possibilities had presented, but also that the nature of the technology, its level of invasiveness and what making it work would mean, would in turn determine where liberalism went, and so on.

COWEN: Next question.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Is Mormonism anti-American? Or quintessentially American?

DOUTHAT: Quintessentially American, surely. I think that there’s —

It’s interesting in that Mormon sexual ethics have repeatedly brought them into conflict with the dominant American culture. That fact and that reality is a sign that there exists some interesting tension between Mormonism and America as a whole.

But nonetheless, Mormonism is — both in its actual lived experience and its theology — is unimaginable without . . . It has an American essence. There’s no more American figure in certain ways than Joseph Smith. The entire Mormon theology is built around an attempt . . . We were talking earlier about how could you integrate Islam, Judaism, and Christianity into one story, and I was failing to give Tyler a good answer. Mormonism is an attempt to do that, not with three religious traditions, but with the Americas. How do you integrate the Americas into what seems like the Old World–dominated story of Judaism and Christianity? And that is . . . To the extent that Mormonism is out to solve a problem, it’s to solve the problem of what about the Americas? What about all this world over here?

In that way and various others that I could go on listing, I think the tensions between Mormonism and the dominant American culture still leaves it quintessentially American, just as . . . Let’s say, the drug culture of the late 1960s was in tension with bourgeois American society at that point, but Woodstock — there’s nothing more American than Woodstock. And in the same way, even when it’s in tension with whatever else is going on in the culture, there’s nothing more American than the Latter Day Saints.

COWEN: Next question.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Hi. One thing that I’ve been seeing a lot of recently is your tweet storm on fertility and the child tax credit. One of the criticisms that keeps coming up is that there’s no reason to think that the child tax credit would actually be an effective movement of fertility rates. So, two-part question: Do you think the importance of the child tax credit is mostly symbolic, or actually effective? And, second, if you were put on a committee and tasked with offering one piece of policy that would raise the American fertility rate in a sustainable way, what would that policy be?

DOUTHAT: So those of us who are involved in the selling of the child tax credit to Republican politicians tended to make an argument that wasn’t per se about the fertility rate. There was an argument that this was a matter of distributional justice, that the tax code was penalizing parents in various ways because of their kids’ contributions to Social Security, and so on, through a rather elaborate schema — that I think was true and correct. That argument had some flaws, but I think, by and large, it was a reasonable argument.

But it was also an argument sort of geared to satisfy the slightly sclerotic ideological preconceptions of the Republican party, and sitting here before you fine people tonight, I’ll just say the goal of the child tax credit is to help people have more babies. That should be the actual goal and when the Wall Street Journal accuses it of being social engineering — it is social engineering, and I’m happy to admit it, and maybe there’ll be a Wall Street Journal editorial about this tomorrow. But I think in the same way that the Wall Street Journal’s preferred economic policies, which they hope will spur entrepreneurship and new hiring and business formation and all these things, are also social engineering in a certain way.

I don’t think that you can . . . I don’t believe in some pristine separation of the economic sphere (which isn’t social engineering) and your tax policies (aren’t social engineering) from the family. The baseline is, I’m in favor of giving people money to help them have the babies that they want to have. Now, would the child tax credit have accomplished that to the extent that it would have much effect? I would say it was a bare and very minimal effect. I think if you look at the literature, you need something much, much larger to have any hope of moving the needle. But I wouldn’t say it’s symbolic. I think it’s a step in the direction that I would like American society to take, which would take us towards something that wasn’t a $2,000 per child tax credit, but a $5,000 per child tax credit and so on, even upward from there. So those are my maximalist ambitions.

Now, it is also true that cultural forms and assumptions and so on play a much more important shaping role in all this, and it might be the case that even if you got to my ideal number that it wouldn’t move the dial that much. But in that case, I would still favor it in part as a means of . . . I think there’s value in building the foundations in political economy for the cultural changes that you wish to see even if those changes haven’t arrived yet. So it might be that the child tax credit’s effect would be counteracted by the deranging influence of screams on people’s romantic lives, or something.

That might be the case. But then the child tax credit would still be there waiting for the Butlerian Jihad of the future.

[laughter]

DOUTHAT: The people who laughed are Dune readers and everyone else is not. It’s good; it’s important at some point in every public event to separate the Dune readers from the non-Dune readers.

But until the moment arrives when we get a handle on our technological problems and achieve some cultural shift. But anyway, yes, the long story short, at least on the roster of plausible policies, that would be the policy that I would offer. And I think the goal is to . . . It probably wouldn’t have that much influence in its existing form, but the goal would be to get to a form where it did have a chance of having influence.

COWEN: Next question.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: In relation to your upcoming book, obviously, there’s been many Christian denominations, like Eastern Orthodox, certain conservative Protestant groups, that have a less strict line on the divorce question without entirely succumbing to the cultural liberalism that’s undermined a lot of Christianity in the West. So in light of that my question to you is, is your objection to the pope’s potential shift so much due to his actual proposals, or more the therapeutic language itself making the case that you find problematic?

DOUTHAT: No, I think it’s the proposal itself. There’s a sort of “sociology of religion” argument that conservative Christians tend to get into that you’re referencing on these questions where you say, “stricter churches do better at weathering the storms of modernity than more lax churches,” and “there’s value in having a church that is explicitly pushing back against cultural trends,” and so on. I think all of those arguments are in some cases plausible; I think they would be plausible in this case. I think a therapeutic shift on divorce would have negative practical effects on the everyday lives of Catholics. But the reason the issue is particularly important to me, and the reason I’ve written about it so much, is that I think the church is risking betraying its connection to Jesus. And that’s . . . The sociological stuff is important, but it’s secondary.

To me, one of . . . I referenced the essential radicalism of Christianity, and obviously Catholicism has not been, in political practice, a radical force at every moment in human history. But one of the great things about the Catholic Church and one of the things that makes me think the probabilistic game that Tyler somehow induced me to play online, one reason I give it a high probability of being the one true church is that there are these core, very strange and radical things that Jesus says and does that are sustained in the life of the church in ways that they haven’t been in other Christian denominations and churches and one of those is the Eucharist, the idea of transubstantiation, the idea that you are literally consuming the body and blood of Christ.

Another of them is this . . . another thing I referenced earlier: this persistence of priestly, religious, monastic vocations, this idea of Christianity as a counterculture to the point where it is actively turning its back on family life in certain ways and retaining this space for a radical core, a radical witness. And another of them is the teaching on marriage and divorce, which in the context of the New Testament is clearly presented as a kind of radicalization of Jewish law on marriage and divorce, and the church has maintained that radical perspective. And I think it’s done so in fidelity to the man that we think was the Son of God, and I would prefer it to continue to maintain that fidelity rather than softly give it up.

COWEN: Next question.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: So I was actually going to ask you about the necessity of a Butlerian Jihad.

DOUTHAT: Good! Good, good.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Since you’re already on board, I’ll skip straight to practicality. What form do you think it should take, how extreme do you think it should be, and would you be willing to lead it?

[laughter]

DOUTHAT: So the Butlerian Jihad is an event that takes place in the universe of Dune, the science fiction novels by Frank Herbert, and takes place in the distant past, although his son wrote some other novels that try and lay out how it happened.

COWEN: They don’t count.

DOUTHAT: They don’t count, thank you. No, I’m a big . . . Dune itself, I’m a huge fan of. I could never actually finish all of Herbert’s novels, which makes me a Dune noncompletist, which means I might be the wrong person to lead the Butlerian Jihad.

But the Butlerian Jihad is this rebellion against . . . I think it is, maybe you can correct me, but it’s AI more that it’s a rebellion against, rather than computers per se, or is it . . .

COWEN: I would have to reread —

DOUTHAT: You would have to . . . Well, anyway, it’s some sort of rebellion against the use of computational replacements for human beings. And so you have this far-distant spacefaring culture that relies on Mentats, these humans who have developed their intellect to somewhat superhuman levels — perhaps through the use of CRISPR — thereby I’m trying to unite all the themes of tonight, Tyler — But they don’t use certain forms of computing power that we would assume people in the far future would. Anyway, that’s the necessary background.

My view for a short-term Butlerian Jihad is much more limited and boring. I think that people should limit or reduce or eliminate the use of computers and screens and digital devices for children and in schools up to a certain age. And I’m flexible and could argue about what that age should be. But I think that young childhood certainly should not be a place . . . I think that young human beings should be given a sustained encounter with actual physical and social reality before being placed in front of a screen. And I think that that should be educational common sense. And that we’ve gone in the opposite direction is an unfortunate thing.

So, I think you start with that and then we can talk about future steps. Like, I don’t know, yeah. We can talk. I don’t want to suggest any, in case I’m quoted out of context, but you can imagine next steps. We’ll just stick with that educational step first.

COWEN: I have a question from my iPad screen right here.

DOUTHAT: I can’t take it, Tyler. The Jihad is happening even as we speak. The wires are being cut. The cloud is being dismantled.

[laughter]

COWEN: “If and when artificial intelligence comes along, how will this change our understanding of religion?”

DOUTHAT: I think that if human beings could actually create consciousness, it would . . . an actual conscious AI — that it would tell us something about consciousness that we don’t currently know, that would have some unknowable influence on theological debates. I think that if you look at where some of the smartest non-Christian, nontheistic critics of eliminative materialism end up, someone like Thomas Nagel or something, they end up in the pantheist or panpsychist kind of vision where mind is a kind of emergent property of the universe. (I might be getting that slightly wrong, but that might be the idea.) I think that there are versions of AI that you could imagine emerging that could be claimed as . . . Well, I don’t know.

There’s something about consciousness that we don’t understand, obviously. And I’m very skeptical of the idea that we’re just going to get through some Moore’s law doubling . . . we’re going to a recognizable consciousness by accident; Skynet is going to become self-aware or something. I think that there would have to be some remarkable breakthrough, and I don’t know what the nature of the breakthrough would be, but I think it would at least contribute something to theological debates about the mind’s place in the cosmos.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Do you think that social media is contributing to polarization and a breakdown of discourse more generally? And, especially, can you comment on its effect on journalists and journalism?

DOUTHAT: Sure. I don’t want to, having done my Butlerian Jihad rant, I don’t want to oversell the horrors of social media, because I think if you look at a lot of the polarization in American life, it’s being driven by an older technology: cable television. And that the effect of cable news on older Americans probably goes a longer way to explaining some of our polarization right now than does social media. So that would be my caveat.

With that being said, I think the effect of social media is its . . . Tyler had an interesting — you had an interesting post about this today or yesterday.

COWEN: Yes, today.

DOUTHAT: And you worked out a kind of Hegelian dialectic of different people on Twitter that I wish I could summarize, but I can’t quite. But at the very least, in my own experience, Twitter and social media generally, it has a deranging effect. It creates a sort of a sense of permanent crisis and sort of permanent alarm and so on where people have their Facebook feeds where they and their friends are sharing things that confirm their view that the world is coming to an end.

And, as a journalist, I feel like I’m often called upon by people in my non-journalistic social circle to sort of reassure them. And of course they’re no longer reassured because during the last election I kept telling them that Trump wasn’t going to be the Republican nominee. And that he probably wasn’t going to be the president. So my level of reassurance has been limited by that.

But I feel like I see a lot of people in my social orbit who aren’t journalists who seem to be — they’re sort of pushed to the edge of panic constantly by what they see in the news and on social media. And then they’ll write to me and ask me to explain what’s really going on, which I may not always be able to do. But to the extent that there’s sort of an obligation for journalists, it’s often, I think, that obligation — to walk people back from the edge of panic, in certain ways.

But in terms of its effect on us, it’s a little hard for me to say, because I wasn’t really a journalist before — I was a little bit; I wasn’t on Twitter probably till 2011, so I had some pre-Twitter understanding. I mean Twitter . . . It’s a forum . . . It’s such a journalist-specific forum in certain ways, it’s so geared towards journalistic culture and everyone is on there arguing with each other and sharing stories with each other and so on. And at its best, I think, it gives people a little more sense of the inner workings of journalism in certain ways, to the extent that I don’t want to be all doom and gloom. There is a virtue in being exposed to watching journalists share stories and have those stories partially discredited and walk back stories and argue over stories and so on. There’s probably value in demystifying some of the work that we do.

But I assume that it can’t help, but have a kind of . . . It furthers already-existing groupthink among journalists and it has a deranging effect on us.

And one of the big challenges (and we were talking about this before the conversation) is figuring out what is real and what is just Twitter. And at what point does just Twitter become what’s real? Right? Because so much of what I do and what people in my profession do is we’re watching a world that’s happening online, even as we’re trying to describe a world that exists offline.

And I am often puzzled by the connection between the two. I can’t tell: How real is the Alt-Right? That is a question that is very hard for me to answer because the Alt-Right is very real on the internet. It doesn’t seem to be particularly real in reality, but maybe social media is reality, or at some point it becomes reality, and then it doesn’t even matter what’s happening out in the real world. I’m not sure, but we’re — at the very least we are at a point there seems to be some huge disproportion between the importance of a phenomenon on social media and its ability to get any number of men . . . Like, Richard Spencer has the same 60 people showing up for all his events. He can do something, he and others can do something like Charlottesville, but there isn’t a mass movement of the Alt-Right. And there are more profiles of Alt-Right leaders in liberal publications than there are avowed Alt-Righters who will actually show up and carry a tiki torch. And so the question is, But does nonetheless the Alt-Right phenomenon allow us to see some buried psychological reality among white Americans? Maybe it does, but it’s just very hard to tell.

COWEN: One minute, last question.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Back to the Catholic Church.

DOUTHAT: Sure.

COWEN: Good place to close.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: If it is in need of revitalization and there is a crisis in the clergy, why can we not open up ordination to anyone who feels that they have a vocation and can comply with any other regulations — such as women and married men?

DOUTHAT: I’ll start with married men, because that’s easier. I think that the . . . In that case, there is not any dogmatic prohibition or claim of a dogmatic prohibition; the church ordains men who have been married and has in the past. At the same time, there are structural impediments: the Catholic bureaucracy is not set up to support priests and their families, and that kind of structural impediment is actually incredibly important to thinking about how such a thing would work itself out.