Rick Rubin has been behind some of the most iconic and successful albums in music history, and his unique approach to production and artist development has made him one of the most respected figures in the industry.

He joined Tyler to discuss how to listen (to music and people), which artistic movement has influenced him most, what Sherlock Holmes taught him about creativity, how streaming is affecting music, whether AI will write good songs, what he likes about satellite radio, why pro wrestling is the most accurate representation of life, why growing up in Long Island was a “miracle,” his ‘do no harm’ approach to working with artist, what makes for a great live album, why Jimi Hendrix owed his success to embracing technology, what made Brian Eno and Brian Wilson great producers, what albums he’s currently producing, and more.

Watch the full conversation

Recorded January 13th, 2023

Read the full transcript

TYLER COWEN: Hello, everyone, and welcome back to Conversations with Tyler. Today I am here with Rick Rubin, the Rick Rubin, who was one of the greatest musical producers. He has worked with, among many others, Jay-Z, Kanye, Public Enemy, many of the stars of early rap music, many of the stars of heavy metal, AC/DC, Red Hot Chili Peppers—five albums there—Dixie Chicks, Johnny Cash, Tom Petty, Mick Jagger, Neil Young, Adele, and many more. And he has done an amazing two-hour Hulu special with Paul McCartney.

But most notably, as of late this January, Rick has a new book out, a fascinating look at creativity, called The Creative Act: A Way of Being. Rick, welcome.

RICK RUBIN: Thank you for having me, sir.

COWEN: What can we all do to become better listeners? I mean to other human beings, not of music, not yet.

RUBIN: I would start with the thought to truly hope to understand what the other person is saying. Most of us, when listening, are formulating an opinion, either in response—what are we going to say in response? What do I think about this? Or looking for something to disagree with, or a piece to latch onto. We take a little piece and then tune out from what’s being said. Any ability to turn our own filters off, forget about what we think, not be analytical at all, and only listen with the idea of truly understanding what the person is communicating.

Then asking questions if there’s anything that we don’t completely understand or anything that might be different, anything that seems odd that the person is saying. I’m not saying challenge them. I’m saying, “Oh, why is that the case? How did you get to that?”

When we truly open ourselves to people, they tell us everything, and we can learn a tremendous amount. Whatever I know is from talking to people. Reading, talking to people. We get information from outside of ourselves. We’re not making it up. It’s not starting in us. So, we are doing a disservice when we’re listening to someone and we’re formulating what’s going to happen next or judging them—anything like that.

COWEN: In music, what is it you do to become a better listener to the music?

RUBIN: I think it just comes out of a love of doing it. Spending time with my eyes closed, listening to something—I did through my whole childhood. My deepest connection to anything was music. It just comes through love and devotion.

COWEN: What is the listening moment in actual Buddhist music that interests you the most?

RUBIN: Say it one more time.

COWEN: The listening moment in actual Buddhist music or Buddhist-inspired music. For me, it’s Tibetan sacred music, but for you, it might be something else. What is that moment in listening to such music that grabs your attention the most?

RUBIN: I think it’s different at different times. The sound of a chime or Tibetan bowl, and listening to how it changes over time, and how it dissipates, and how it hangs in the air for a period of time that seems impossible, and how we can hear it get quieter and quieter and quieter. It gets so quiet eventually, you can’t tell—are we still hearing it anymore? There’s something about what is and isn’t here that comes up through that experience of questioning our own senses of what we’re hearing and what we’re not hearing. I like that feeling.

COWEN: You talked about that hanging sensation from Tibetan bowl music. What is a moment of hanging or near-hanging silence in so-called popular music that you find fascinating?

RUBIN: Let me think about this a bit.

[pause]

RUBIN: I would say the closest thing that comes up is in classical music, in the different interpretations of the same pieces. When you’re familiar with what’s coming, and it doesn’t happen the way you think it’s going to happen. It’s written, and the notes are the same notes. The first one that came to mind was Glenn Gould’s early version and later versions of the Variations.

In the early one, it’s played very quickly, a great deal of dexterity. In the later one, there are times when the next note seemingly never comes. It’s fascinating. I actually prefer that one. That gives me that same feeling of the notes hanging in space.

It’s also interesting that the rhythms change, where once we understand a certain rhythm that the notes come in—we learn that in learning how a song goes—to hear them come in a different rhythm, it’s fascinating. It really just lights up things in the brain.

COWEN: I believe that later Gould recording is 79 minutes, whereas the first Gould recording is 45 minutes. Some of that is adding the repeats, but he’s also playing much more slowly.

RUBIN: Yes. I feel like in the speed, in the slowness of it, there’s so much more emotion between the notes that we can feel. The earlier one is a showier rendition, and the later one is more of a soulful rendition for me.

COWEN: As a music producer, what do you think of the 17 minutes of silence before the final track on Nirvana’s Nevermind album?

RUBIN: I think it’s cool. Anything that breaks the norm is interesting. It forces the listener to engage in the music in a different way. The purpose of something like that is to feel like the album’s over, and you’re going about your business, and you forget you’re even listening to it. Then you’re surprised by this thing that happens. It forces you to pay attention in a way that doesn’t come so naturally. It essentially tricks the audience into forgetting that they were listening to music.

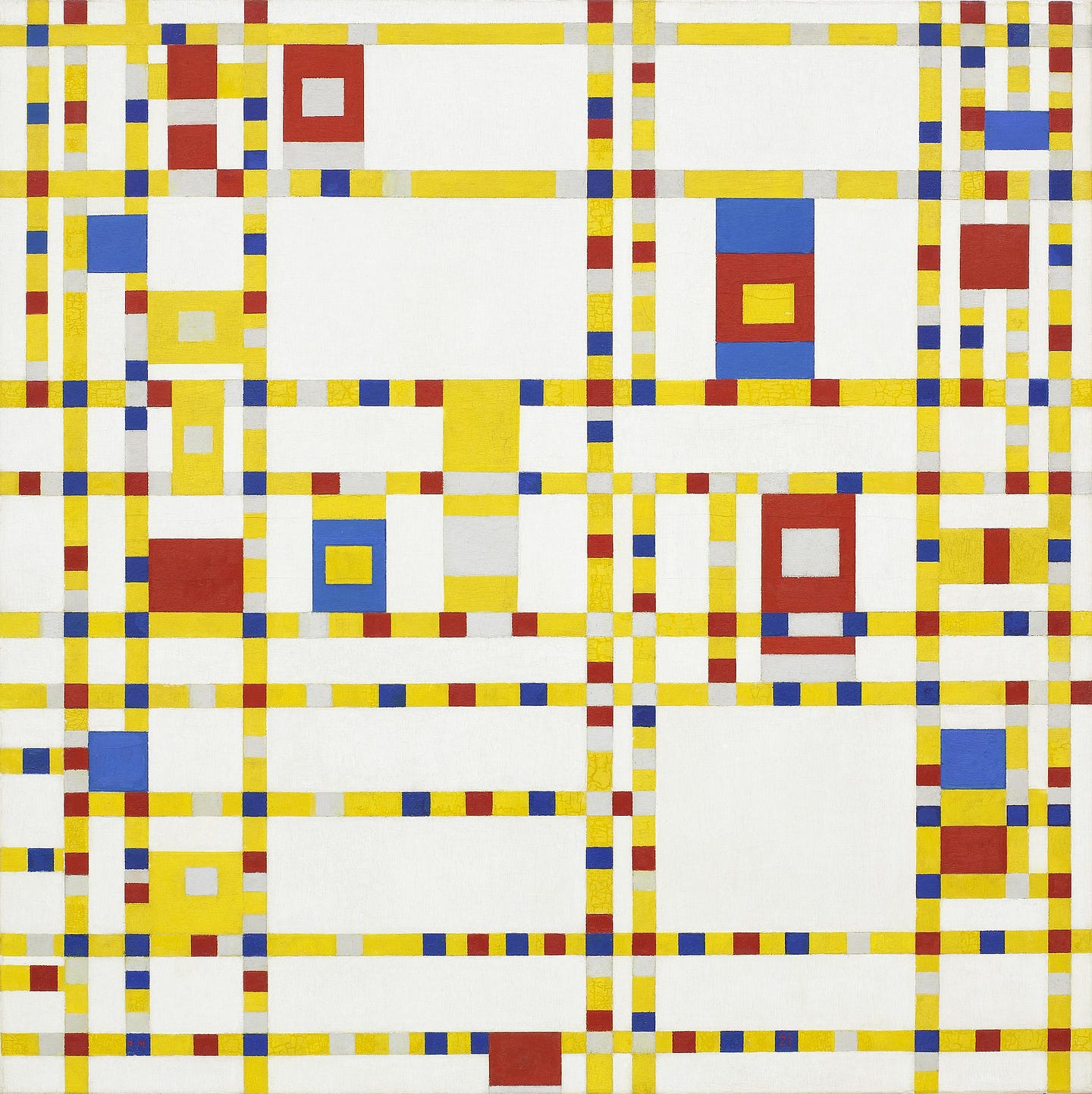

COWEN: How have you been influenced by the painter Mondrian?

RUBIN: He’s one of the painters that really spoke to me when I was going to film school. I remember being fascinated by the geometric shapes, the particular colors, the way it made me feel, and the fact that I was living in New York at that time, and it had an urban sensibility. It almost felt like a subway map. There was something about it that just spoke to me, that changed my understanding of what fine art could be.

COWEN: Now, as you know, the New York avant-garde of the ’50s and ’60s was greatly influenced by John Cage. You’re coming a bit later, coming of age in the ’80s. Is that an influence on you as well? And if so, what did you take from Cage?

RUBIN: One of the greatest things I can remember reading was a story in Cage’s book. I think it’s called Silence. He tells a story where he’s driving. He’s on his way to do a Q&A. He was going over the five answers that he prepared that he would use randomly for whatever questions were asked. I just thought that was beautifully Cageian. It was beautiful that his philosophy extended past his music to a way of being in the world. I really appreciated that.

COWEN: What does it mean to have a moment of silence or near silence in rap music—which seems to always be moving, right? Does that work?

RUBIN: A moment of silence in your silence?

COWEN: No, in rap music.

RUBIN: Yes. You could definitely have a moment of silence. I’m sure I’ve produced records that have moments of silence in them, where we’re doing a transition from one energetic feel to another. There’s one that comes to mind. I think it’s on a Beastie Boys’ album, where there’s a certain rhythm pattern going for a period of time. Then the song stops, and then a new thing starts. It’d be like a reprise of sorts, but similar to what we discussed with the Goldberg Variations, it comes back in half-time or a much slower rendition to what was happening before to shed new light on it.

COWEN: What from non-Western music has influenced you the most?

RUBIN: I think minimalism in general. I would say minimalism in art has probably influenced my taste, and my taste influences the work that I make. The idea of trying to use the least amount of information to get a point across. I would say, also, poetry probably has had an impact in that same way.

COWEN: What do you think of pygmy vocal music?

RUBIN: Like the Tuvan music?

COWEN: No. It’s a lot of hocketing. It’s not throat singing.

RUBIN: I’m not aware of it.

COWEN: Highly complex. You should look into pygmy vocal music. I’ll send you the reference afterwards.

RUBIN: Please send it to me. Thank you.

COWEN: What have you learned from Sherlock Holmes stories?

RUBIN: To look closely at things, to look deeper, to pay attention, to notice what maybe others aren’t noticing.

COWEN: How exactly do you characterize his special skill? Because to the outside reader, it seems like he’s making things up. Are those acts of creativity on Holmes’s part, or are they acts of noticing?

RUBIN: I think they’re the same thing. I think creativity is acts of noticing. Nothing comes from us. The creator isn’t making the thing. The creator is recognizing the thing, noticing the thing, and then sharing it in a way where the audience can hopefully get a glimpse of what we’ve noticed.

COWEN: Is contemporary music too loud? There’s a brightness to the sound, right? Especially digital production.

RUBIN: It doesn’t bother me one way or the other. [laughs] I like music that sounds good. There’s some music that I think sounds very aggressive and abrasive and essentially too loud that really works. Probably I don’t listen to very much of that music, but I would say if I was looking for a particular energy in music, whatever would sound too far in that world would probably sound right to me.

COWEN: Do you think the widespread advent of streaming threatens the economic viability of a successful ecosystem for musical production and sale?

RUBIN: I think it can be. I don’t think it is yet. If you look at the history of recorded music, at the time that the Beatles were making albums, I think they were paid several pennies per album sold. Then over time, the artists got more leverage and were able to negotiate better deals. I think it finally culminated in the old music business with Michael Jackson, who was getting maybe $2 per album that was sold, which was much more than everybody else. In the early days of singles, people were paid very little.

Every time there’s a new format of music, the rights holders seem to take advantage of that. When CDs first came in, artists got paid less on a CD than they did for vinyl, and it’s been like that every time. Every time there’s a new format, the artist gets paid less. Now, they only get paid less until their attorneys realize, “Oh, in our next deal, we’re going to negotiate to have better digital rights,” or better whatever it is. Then it eventually evens out because, ultimately, the artists have a great deal of leverage.

Like now, for the handful of the biggest artists in the world, they probably make more money through streaming music than anyone has ever made in the physical world of music, but it’s very much of a top-down thing. It’s only the very top percent who have that. Eventually, hopefully, it’ll get more equitable. It always has. In every case, it has, so I’m optimistic that it will again.

COWEN: Do you worry about the decline in music education in American schools? Does that matter for popular music in the future? Or do people just teach themselves? There’s YouTube, there’s streaming, whatever.

RUBIN: I don’t think it matters. I like the idea of learning what you want in school, and if you want to learn music, it would be nice to have that option. But I think that people learn the things they love, whatever they are, not when in school.

COWEN: Some commentators have argued that because of streaming, listeners consume too much old music and not enough new music. Indeed, if you look at Spotify data, how much people listen to older music seems to be rising steadily. Is that good? Is that bad? It’s a sign of good taste? It makes it harder to break in? How do you think about that?

RUBIN: I don’t think about it. I don’t think it matters. If people are drawn to older music because they prefer it, that’s fine. I think the idea of people listening to what they like is a good idea. On occasion, there’s a new piece of music that really captures someone’s attention.

I’ll say the most difficult thing about it now is that all of it has a disposability that it didn’t have before. In the old days, you would buy a piece of music. You would own it, and you would be invested in that piece of music as yours. Now everything is available, which is fantastic and I love it. As a fan, I love it.

When something comes out by an artist that you love, it doesn’t have the same gravitas that it once had because it’s on this conveyor belt of music that’s always going by. So, even the thing you love—you listen to it, but then there’s something new right behind it, coming right behind it, always something new coming right behind it. I don’t know how the music of today can get to the point of the canon of the music of the past based on that short term, the fact that the music goes by so quickly. Even the things we love—the shelf life is very short now.

COWEN: Or very long, right?

RUBIN: It really changed with streaming. It really did. That was the biggest change. I was very pro-streaming early on. I’m surprised. I didn’t know that that was going to be one of the things that changed, but it’s interesting. With all of these things, we never know what’s going to change. We take what’s good and think about the parts that aren’t as good.

But ultimately, knowing that if this afternoon, I want to listen to the Talking Heads, I don’t have to go to the store to try to find it, that I could listen to anything I want to listen to anytime, just on a whim—it’s a really beautiful way to live.

COWEN: Five years from now, do you think artificial intelligence will be creating good and interesting music?

RUBIN: I don’t think so, but I don’t know enough about it. I feel like what makes art good is the point of view. It’s not the actual content itself, but it’s the humanity in it. It’s the soul in it that makes it good. I don’t know that AI-generated art will have the soul. The soul is that element that makes something. Otherwise, it’s just decorative art, I would say, at this point.

COWEN: Is current satellite radio realizing its potential? How could it be better?

RUBIN: Hmm, I quite like it. I like the fact that it’s in most cars. I feel like I get to hear music on satellite radio that I don’t hear in other places. I listen to the Frank Sinatra channel quite a bit and I love that, and the Grateful Dead channel. I’m relatively new to the Grateful Dead. I like those very much. I don’t know how it could be better. Be interesting to think about, though I’ve never thought about it. I’m happy I have it.

COWEN: I’d like for there to be more single-artist channels. I like it very much, but the idea of overdosing on an artist for two weeks and then moving on, to me, is quite appealing.

RUBIN: Yes, but if it was overdosing for two weeks, if everybody did that—

COWEN: [laughs]

RUBIN: —then having—I don’t know who it’d be—The Cure channel for two weeks would be great. Then, when everybody has had their two weeks, and The Cure channel is there forever, considering satellite seems to have a limited bandwidth—is that true? I don’t know that either.

COWEN: I believe so, at least in economic terms, but they had a Led Zeppelin channel for two weeks. I would have gladly had that for a year or longer, but it seems they can just set up temporary channels if the rights holders agree.

RUBIN: Yes. I listen to the Beatles channel all the time. I love the Beatles channel.

COWEN: As do I.

RUBIN: It was funny, when I was talking to Paul McCartney, one of the first things I said to him was like, “Oh, yes, you make all the music that’s on the Beatles channel, right? That’s who you are.”

[laughter]

RUBIN: “You’re the guy who makes the music for the Beatles channel.”

COWEN: When you were speaking with McCartney, what was the most McCartney-esque moment or anecdote that you have from that? Which part of that was supreme McCartney for you?

RUBIN: I think when he went to the piano and started playing. There was one point where he was giving me a lesson about how to write a song, and the way he teaches children to write songs. It was very rudimentary. He was playing along and showing me something very simple, and he was playing it over and over again. Then all of a sudden, through this exercise of very simple, nothing changing, all of a sudden one of the incredible Beatles songs [laughs] comes out. I couldn’t believe it. I couldn’t believe it was that simple. Watching it happen was mind-blowing.

COWEN: You’ve watched the Get Back sessions movie by Peter Jackson? As a music producer, what’s your takeaway from that?

RUBIN: As a Beatles fan, I just love seeing anything with the Beatles in it. I can’t get enough.

COWEN: It must have, in some way, revised your view of the Beatles. What’s the Bayesian update, so to speak?

RUBIN: Did you ever see the movie about Metallica? Metallica made a movie. I think it was called Some Kind of Monster.

COWEN: No.

RUBIN: What’s interesting about that movie is, they’re the biggest band in the world at the time that they make the movie. They make this documentary film, and in the film, they’re completely lost. Completely lost creatively. I thought it was really bold for them to put it out because it was so revelatory. I suppose, because I’ve been around a lot of musicians at all different stages of their work, the idea that until it’s really good, there are times when nobody knows what they’re doing—that’s normal.

I guess the thing that I took away as most astounding was when a song would pop up in the movie, out of seeming boredom. Just a song would pop up, and it would be songs that we’ve listened to our entire lives. It was thrilling, and it was a reminder of, that’s what it’s always like. Yes, on the one hand, it’s shocking, and on the other hand, that’s what it’s always like.

COWEN: I was struck by just how much Paul was the guy who got things done. I had always known that, but the extent of it, seeing it before your eyes, to me, was a shock.

RUBIN: Yes. He was the craftsman in the Beatles. He was the record maker in the Beatles. Everyone brought something really special to the Beatles. That said, Paul, in many ways, was the glue that allowed it to be what it could be.

COWEN: What is, for you, a very underrated solo Paul McCartney song?

RUBIN: Maybe Helen Wheels.

COWEN: Why do you like that?

RUBIN: I don’t know. I just remember hearing it on the radio when I was a kid, and it sounded different than other things. I think it’s the difference of it. I don’t think he has any other songs quite like that.

COWEN: Putting aside all the people you’ve worked with, but who or what is it in music right now that you’re especially excited about? The sense of looking forward to something when a certain book comes out. Your book’s not out yet, but I have a copy, but I was looking forward to that in some very definite way. What is it you’re looking forward to in the current stream?

RUBIN: It’s funny, but I like pro wrestling. WrestleMania’s coming up in April. I’m looking forward to WrestleMania in Los Angeles.

COWEN: Why do you believe pro wrestling is the most accurate representation of life, as you once said?

RUBIN: Yes.

[laughter]

COWEN: You’re free to repudiate your own words, but—

RUBIN: No, no, I’ll stand by that. [laughs] That sounds solid. Pro wrestling is art made up. It’s made up and rooted in real life, and real life is made up and rooted in real life. Wrestling is a more honest depiction of the world than everything else that acts like it’s not made up.

COWEN: Who is the pro wrestler in particular that you look forward to?

RUBIN: This season it’s Roman Reigns, who’s the head of the table. He’s a fantastic character these days.

COWEN: What’s your favorite opera and why?

RUBIN: I don’t listen to very much opera. I listen to the Maria Callas channel on Pandora sometimes, but I don’t know what pieces come from where.

COWEN: I like Don Giovanni very much. Perhaps that’s my favorite.

RUBIN: Maybe I’ll start with that one. Is there a particular version?

COWEN: Oh, I think Currentzis is the best, Teodor Currentzis. Then Colin Davis would be my second choice, but there are many fine recordings of it.

RUBIN: Please send me links to both.

COWEN: I will send you that, absolutely.

RUBIN: Both, because I like to compare.

COWEN: Great. You came of age in New York City. You went into hip hop early on, but you went to all these punk clubs from what I gather. How did that feed into your work on heavy metal and hip hop, this punk background?

RUBIN: I was a punk fan before I was a hip-hop fan. The punk revolution was really exciting to me because it felt like it was being made by people who weren’t technically musicians. The music that it was replacing would be things like Electric Light Orchestra, who I love as well—these very studied virtuoso musicians.

Punk rock came along, and it was anti. I liked that idea that this is for everybody. It was really a democratic kind of music. It seemed to be young people who had energy, usually anger against things that they saw that didn’t seem right. Now, in England, it was all about class struggle. In the US, my experience of life, class struggle didn’t really exist.

When American bands started doing music inspired by English music, talking about class struggle, it didn’t really resonate with me. Whereas the Ramones were my band. The Ramones had the energy of punk rock, but lyrically, they weren’t an overtly political band, which made sense for the world that we grew up in. Where I grew up was not so far from where the Ramones grew up, and it made sense for our world.

The first American punk band . . . The second-wave punk band that really made sense to me was Minor Threat, and that was Ian MacKaye’s band. He later had a group called Fugazi, which is fantastic as well. Minor Threat talked about social issues that were applicable to our life, so it felt more true to me, and I loved their music. I loved the energy of punk rock music. I felt like a lot of what I liked in heavy metal, growing up before punk rock, was even more charged in punk rock, and I tried to bring that aesthetic.

When I say I tried to bring that aesthetic, it’s not really right. That’s looking back. At the time, the music I liked was punk. I experienced the energy of punk. Then, when I was making heavy metal records, let’s say, because I had the love of punk rock, I understood this extra gear that the music could go to that it hadn’t gone to in the heavy metal days but did go to in the punk rock days. For example, Slayer trying to bring the power of punk rock, but with the precision of heavy metal because Slayer was a heavy metal band. They were a punk rock heavy metal band, but they were definitely a heavy metal band.

COWEN: Did you draw much, if anything, from disco in those days? Or that was anathema?

RUBIN: No, I always loved disco. I may not have loved all disco, but I like dance music. I love all kinds of dance music, and the best of disco is the best dance music.

COWEN: You grew up in Long Island, is that correct?

RUBIN: Yes.

COWEN: Do you feel that growing up in Long Island rather than, say, Manhattan has helped you understand the music of the rest of America better? If so, how?

RUBIN: I would say growing up where I grew up was a miracle. It plays such an important role in my understanding of or relationship to culture. Not growing up in Manhattan was more of an experience like the rest of the United States, but I was close enough to Manhattan to be able to get there. I could go to a museum, I could go to a Broadway show, I could go to the theater. I could do things that, if I was growing up in a truly rural place, I couldn’t do.

In some ways, I had the best of both worlds. I was close enough to get to the city and understand what was going on in fine art and live in the suburbs and experience what Americans like. It was, again, pure luck. Luckily, my tastes share those two. I got to experience both of those lives growing up, and either one of them without the other would be out of balance for me.

COWEN: Having grown up in New Jersey, I feel very much the same way.

Now, you once said—I’m not sure if this was ironic or serious—but that for you, the ideal act of musical production would be never to even meet the artist. Did you mean that literally? Or how should I interpret that?

RUBIN: Yes, that’s true. You interpret it how you like. I meant it literally.

[laughter]

COWEN: Why is it better not to meet the artist? Some art collectors—they say, “I never want to meet the painter. I just want to look at the painting more objectively.” Is it like that?

RUBIN: The idea is having the biggest impact on the work with the least amount of fingerprints. I want the work to be wholly the artist’s work. The less I can do, the better, provided it’s the best work the artists have ever done in their lives. My role is to support the artists in doing the best work of their lives. Again, if it’s needed, my fingerprints are all over it, but my preference is to have as little involvement as possible.

The ultimate version of that would be to know that an artist wants to work with me, for that somehow to be arranged, for me to never meet the artist or speak to them, and have them make the greatest work of their lives, knowing that we have this connection.

COWEN: Is this related to why you don’t use more editing software?

RUBIN: When do you mean, using editing software? [laughs] Explain.

COWEN: Well, you’re the one who’s there. I’m just guessing from what I hear, but I have the sense that the decisions come from you interacting with the artists rather than you doing everything at a board, giving commands to software. But again, your account is the definitive one.

RUBIN: I share my opinion, and more often than not, in some cases . . . let’s say I listen to a body of an artist’s work, and they ask my opinion, and I’ll make 100 notes. And I’ll know inside of myself that of these 100 notes, maybe 5 of them will make or break the work. I’ll share all 100 notes, and if the artist chooses not to incorporate the 5 that I know are going to make a difference, then I might have a second conversation. But still, it would be ultimately the artists, always the artists. I don’t want to convince anyone of anything. I would like to state what I see, and then it’s up to the artist to take that information and use it as they wish.

COWEN: You must be an above-average persuader, right?

RUBIN: I feel like I have that ability, but I don’t like to use that ability. I feel like it’s a—

COWEN: Maybe that’s why you’re above average.

RUBIN: Maybe. I feel like getting someone to do what you want—that’s not the reason for somebody to do something. I don’t like that idea.

COWEN: Say you’re George Martin. You’re at Abbey Road Studio, and George Harrison thinks Paul McCartney wants to put too complex a bass line into something, or into While My Guitar Gently Weeps, which in my opinion made those songs much, much better. You’ve got to persuade someone of something, right?

RUBIN: I don’t know about that. And I’m not sure that that’s how it went down. Do you know what I’m saying?

COWEN: Yes.

RUBIN: I don’t know that. I think more often than not, the people involved in the making of art who are not the creator do more harm than good, so I’m very much of the mind not to do harm. I don’t think that I know everything. I don’t think that my opinion necessarily has more validity than someone else’s, so I like to really have the conversation and get to the bottom of it through talking.

Ultimately, I’ve had it happen where artists will just flat-out reject what I’m saying. It’s like, “That’s fine.” And I’ve had the opposite. I’ve had artists say, “Tell me more. I want to do more of what you want.” I’m open to doing it. I’m open to participating as much as they want, but I don’t want to convince someone to do something, even if I think it’s better. I don’t feel good about that.

COWEN: You’ve also claimed you don’t really play any musical instruments. Now, that’s a matter of degree, but you feel that helps you as a producer?

RUBIN: That it helps me that I don’t?

COWEN: That you don’t very much, you must admit, right?

RUBIN: Yes, but I honestly don’t think it helps or hurts. It just is what it is. My involvement is purely about taste. It’s not about technical skill. It’s not about technique unless there’s something that I noticed in the past that I shared, like, “Oh, I remember so-and-so did it like this. Do you want to try that?” That would be the extent of something either technical or musical. But other than that, it’s more, “This is the part that’s interesting to me. This is the part that’s less interesting to me. Is there any way to make this part that’s less interesting as interesting as this part?” That’s most of my job.

COWEN: How much of your value-added do you think is choosing the right talent? One of my friends, who’s a fan of yours, described you as one of the greatest venture capitalists of all time. You could see or feel that certain artists had it in them to do great work—with you or with others. And a lot of them were not well known until you worked with them, so some of it is you made the music better, but some of it is you chose properly. What is it you look for when you’re choosing people to work with?

RUBIN: I would say it’s like falling in love. I can’t say why. It’s, why do you love something? Why do you love the things you love? It’s not intellectual. It’s a feeling and you feel it, and you want to hear more. You know you want to hear more. You lean forward. You want to hear more. There are certain artists—when they make music, I want to hear all their music. I am less focused on, “This sounds like a hit song.” I don’t care so much about that. I’m more interested in how I perceive the artist and whether I’m interested in their body of work or not.

COWEN: When you were a kid, you said you did a lot of magic tricks. How did that influence your later approach to music production?

RUBIN: Certain things like understanding misdirection, or the surprise that comes up in the juxtaposition of things that creates an illusion, those things work in music. I can’t think of a song in particular, but there’s a song that starts . . . the first song on an album that starts with a very small sound, and it’s rockin’, but it’s a very small sound, and it goes on for a while. Then it breaks into a very big sound.

Because there’s no context before the small sound, and the small sound goes on long enough, you might think that’s the whole thing. That’s what it is. That would be something that would be rooted in a magician’s principle of creating a certain expectation, and then the surprise of changing it is enthralling for the audience.

COWEN: Why is it that there are so few really good live albums? Or perhaps you disagree. Or is there something that’s just very difficult in their production? The Who, Live at Leeds, James Brown at the Apollo, Nirvana MTV special, Allman Brothers, [At] Fillmore East, and Johnny Cash, At Folsom Prison. There are some. I even like Wings over America, but there aren’t that many I really want to go back and listen to it.

RUBIN: I’m thinking about why that is. Kiss Alive was another seminal . . . Kiss Alive II was actually . . . they broke based on live records. And Frampton Comes Alive was another.

COWEN: That’s good, yes.

RUBIN: There’s another one. My favorite—I mentioned earlier, I’m new to the Grateful Dead. Their album called The Reckoning is my favorite of their albums. That’s a live album. It’s a live acoustic album. Most jazz records are ultimately live albums. Even if they’re live in the studio, they’re live albums.

Maybe the difference between a great live album—if we consider jazz albums, the reason an album might be better live in the studio, instead of live in front of an audience, isn’t so much because the audience is there, but just because of the ability to record it better. That would be my guess, because so many rock records we like, studio albums are essentially live records in the studio, the greatest ones of all time.

COWEN: I once saw Plant and Page live, and they were very tight, but I came away with the impression that Led Zeppelin was more of a studio band than I had thought, that there was a sense of texture in the actual albums that was missing in the concert. I felt a little flat going out. “Oh, I’m supposed to love these guys.” I do love them, but it wasn’t the same for me. Then I saw a current version of Queen, and you think, “Oh, they’re the ultimate studio band.” And they were amazing live. I was still puzzled over that.

RUBIN: Yes, the production is a big part of it. In the case of Led Zeppelin, Jimmy Page’s production is astounding. It definitely takes it beyond what the live recording can do. In the case of Led Zeppelin, it starts as a live recording in the studio, and then he adds layers and layers of embellishment that make it a symphonic recording rooted in a live rock band recording.

If you see the Ramones’ first album, it’s recorded all . . . or the Beatles’ first album was recorded just quickly. Black Sabbath’s first album was recorded in a few hours. Those are essentially live records, and I think the reason that they might sound better . . . or I guess the MC5’s first album is a live album too.

COWEN: Should I think of Black Sabbath as just being jazz?

RUBIN: You can. It’s very jazzy. It’s very, very jazz-influenced, and that’s why they’re great.

COWEN: As I’m sure you know, Jeff Beck sadly just passed away. How is it you think about the nature of his genius?

RUBIN: I think he’s one of the greatest guitar players of all time, maybe the greatest. What I love about him is that he plays the guitar as if it’s a different instrument than the instrument that everyone else who plays guitar plays. He plays it in a completely original way. He found a new language of guitar playing that’s only his, and that only he can do, or that I know of that only he could do. It’s astounding and breathtaking to watch. I absolutely love his playing. Now, I might not like all of his music, but I love his playing.

COWEN: How should I think about the production of the Jimi Hendrix trio? You have just three guys, not very high-tech, and ultimately, it sounds like planets are colliding. What is it they did that made that work?

RUBIN: He used so many new original techniques for the time with effects, with panning. He really used the studio. He was one of the first to make the studio part of the group. I have an interesting story to tell you that came from an interview I did with Johnny Echols, who’s the guitar player in the band Love. Are you familiar with the band?

COWEN: Of course. Forever Changes, among others.

RUBIN: I love that album. That’s why I was interviewing him. I talked to a few different people. Everyone who was involved in Forever Changes who’s still alive, I spoke to. He told me the story about a guitar player named Jimmy James who wasn’t really a guitar player; he was more of a roadie. He was a roadie and driver for Little Richard. Little Richard needed a guitar player live, so Jimmy James would fill in on guitar, but he wasn’t really a guitar player. He was more of a roadie and a driver.

The guys from Love hung out with the guys from Little Richard’s band, and they were all friends. One day they get a call—oh, I left out a piece. Okay, there’s an invention called Vox Wah-Wah pedal, which was given to all of the guitar players in all of the popular bands as a promotional tool. Jimmy Echols got this Vox Wah-Wah pedal, and Jimmy James got one even though he wasn’t really a guitar player, but he played for Little Richard, so it was high profile.

All the guitar players got them, and the pitch from Vox was, “This pedal will make your guitar sound like the trombone.” And Jimmy Echols got this thing, and he said, “Well, if I want to have a trombone on my record, I’ll learn to play trombone,” and he threw the Vox Wah-Wah pedal in the garbage.

Then a year later, 18 months later, they’re in Los Angeles, and they get a call that there’s this incredible guitar player from England named Jimi Hendrix. “You have to see him. He’s playing in San Francisco.”

They drive up to San Francisco, all excited to see the greatest guitar player we’ve ever seen. Jimi Hendrix comes out on stage and starts playing, and it’s Jimmy James. It’s Jimmy James, who was the not-so-great guitar player who 18 months ago was the roadie for Little Richard. He was playing through the Vox Wah-Wah pedal. The Wah-Wah pedal made Jimmy James into Jimi Hendrix.

The point of the story that Jimmy Echols was telling was, the reason that Jimi Hendrix was Jimi Hendrix was because of the way he embraced technology. That’s what made him the guitar-playing god that he is, was because he was the first guitar player to embrace the technology.

COWEN: What made Brian Wilson an important producer?

RUBIN: He heard things that other people couldn’t hear and would make the effort to get them onto tape so that we could all hear them. And they were often unusual things, very beautiful things, very beautiful harmonies and arrangements that might not make sense to anyone else at the time.

COWEN: He had amazing silences, I think, in some of the Hawaiian songs: “The Little Girl I Once Knew,” many others, “Vegetables.”

How do you think about the main contribution of Brian Eno to musical production? Obviously, incredible in many ways, but as a producer?

RUBIN: He seems to be the one who really broke down the walls of anything sounding like a band. I think up until the time of Eno, the idea of the band being the centerpiece of the recording was the thing that you built on or veered from, but it was the central idea, was the sound of the band.

I think his idea was music is music, and it’s not about the band. It’s about the sounds. Whatever sounds put together in an interesting way is what it is. If Jimi Hendrix embraced the recording studio to take it as far as it could go for a rock band, Eno took the rock band out of the studio and just left with the studio.

COWEN: The Van Morrison album Astral Weeks—why does that sound so special? Obviously, great songs, but there’s something about the feel of the album on the LP. What is it?

RUBIN: I think it’s a combination of the songs, obviously, Van’s voice is unbelievable, and the sensitivity of the jazz musicians playing. Hearing great jazz musicians playing technically non-jazz music is a really thrilling thing. I tend to like when jazz players play pop music. I think we hear that—

COWEN: Keith Jarrett playing Shostakovich.

RUBIN: Beautiful.

COWEN: That’s fantastic.

RUBIN: Beautiful.

COWEN: Very different sound.

RUBIN: I think, in general, having someone who’s good at one thing playing something else is a good idea. I just learned this story recently. I produced Neil Young’s last album, called World Record. The band on the album was the same band who he recorded After the Gold Rush with 50 years ago. Nils Lofgren was the guitar player. It’s funny because I think of Nils as a guy in Bruce’s band, but before he played with Bruce, he played with Neil.

While he is an unbelievable guitar player—was then and remains today—Neil wanted him on After the Gold Rush to play piano, specifically because he doesn’t really play piano. Neil wanted someone to play piano who really understood music and felt music, but didn’t really play the instrument that they were playing. Some of the most memorable pieces of that After the Gold Rush album are rooted in Nils not knowing how to play piano and Neil’s understanding that that’s what it was.

An interesting thing in dance music is that the most interesting dance music that I’ve heard seems to be made by people who didn’t only listen to dance music, like people who came from punk rock and then started making dance music.

LCD Soundsystem is a good example. James Murphy was a punk rocker. He was the soundman at CBGB. When he brought his sensibility to the world of dance music, not being of dance music, it creates this new energy and light in it that people who have only made dance music—it always seems more ordinary to me when the people who are good at it just make it. When someone who doesn’t make it makes it, we learn something new, and when we learn something new, it’s always the most exciting, always the most exciting.

COWEN: Do you have a favorite Neil Young story that you can share?

RUBIN: Well, I’ll tell you a story about this new album that we just made. It was an experience unlike any I’ve had before. We recorded for the first week. Neil comes in with songs written. Normally the way it works is, he comes in with songs written that he can play, and he plays the song for the band one time, and then the band plays along with him, and it happens very quickly. That’s the way it happens with Crazy Horse, I think with everybody, but with Crazy Horse in particular.

With this album, Neil wrote the songs in a different way, so he didn’t know them. In the past, he would write songs on guitar and he would play around on the guitar, find chords, write a melody, write words, have the song, know the song, and then come to the studio being able to deliver a solo performance.

In this case, he was hiking and whistling, and he noticed that the whistling was interesting, so he started recording the whistling, and then after recording the whistling, he realized, “I think there’s enough whistles here of melodies that are interesting, that this could be an album of songs.” He’d never done that before, just channeling these melodies. The writing is unlike any Neil Young music you’ve heard before because he’s never written this way before, and it’s just a different process and came out different, and beautiful. It almost seems like it’s from another time. It seems like it’s from a time before Neil Young.

He has these whistles. He sat down to write words to the whistling, which he did for all the songs in a two-day window. He wrote all of the words with no revisions and no changes, which is something that he said has never happened to him before in his life. Then he came to the studio with all of his instruments, and he would try to learn the song—how he was going to do the song. While he was learning to do the song, the band was learning the song, the changes.

We did this for the first week, and it was really a mess. It was a mess to the point where Neil got to the point where he was able to play the songs, but it didn’t sound like the band would ever be able to play the songs. I can’t tell you why it felt like that, but it just sounded completely lost. That was our first week of recording. I will tell you I was concerned, but we’re thinking, “Okay, maybe next week. Maybe this will be the first step in learning the songs, and next week they’ll learn the songs and be able to play them.”

We get to the second week, and we’ve gone through all the songs in that first week, and now it’s the first day, Monday of the second week. Neil says to Ralph, “Let’s play this.” He names one of the songs. Ralph the drummer says, “We already played that one.” Neil’s like, “Let’s try it again.” They’re like, “I think we did it good.”

There was this sense of like, were we watching the same movie? Because it was so far off. On the second week, we tried doing some of the songs again. Ralph was not really into it. He’s like, “I feel like we already played them.” We play them again, and it’s certainly not better.

Then Ralph’s like, “Let’s listen back to that first week. I think it was really good.” We go back and we listen, and you could hear there’s something there, but it’s so hidden in mistakes. I don’t even know how to describe it because it truly was a mess, but if you really listen to the mess and say, “Okay, let’s take out that instrument in that spot. Okay, what does that sound like? What about if you turn up this guy in this spot?”

We went through it, and I would say the entire album was recorded in that first week when none of us knew. I certainly didn’t know it. Neil didn’t know it, for sure. At the end of the first week, he’s like, “Wow, I hope next week’s going to be better than this.” [laughs] It was wild. That’s the first time I ever had that experience. I think it’s a beautiful album. Now it transformed. We did a lot of work to help it transform, but the fact that it was unrecognizable to being something that’s so beautiful now. It’s different. I’ve never had that experience before.

COWEN: I will buy that one. What was Johnny Cash like?

RUBIN: Beautiful, quiet, soulful, really smart, knew every song ever written up to a certain period of time. He didn’t know modern music, but he knew the history of music through probably at least ’70s country music. Seemed to know everything about history and knew a tremendous amount about religion, spirituality, and Christianity.

COWEN: Last two questions. First, your new book—again, the title is The Creative Act: A Way of Being, but what does that book mean to you? Final question, in music, what is it you might be likely to do next?

RUBIN: The book is an attempt to share the type of thinking that happens in the recording studio with the artists that I get to work with. I’m hoping that it can open someone’s mind to possibilities of a different way of doing things. I don’t know that it’s for everybody, but if it’s for you, I hope that you know about it.

I had an interesting experience. I read two reviews of the book in two big financial newspapers. One of them absolutely hated the book. I read that review first, and it just made me laugh because it’s like they didn’t feel the book at all. Then, I read the second one and they loved the book. It was so interesting to see these two opposing points of view about the same piece of work. It made me feel good because one of the things I talk about in the book is that the best work divides the audience, and that you want to make work that some people love and some people hate.

If everybody thinks it’s just okay or pretty good, it’s not so interesting. If everybody likes something you make, you probably didn’t go far enough. You want it to be extreme enough that the people who love it really love it, and that everyone else just doesn’t—it’s too much. I got to have that experience today, and it was a great experience. I hope that the reader of the second piece who really felt it—I hope that people who read like him are able to have the experience of reading the book. I don’t want anyone to read it who doesn’t want to read it or isn’t into this kind of thing

COWEN: What you will do next—I don’t mean another book, but musically, is there something slated that you can talk about?

RUBIN: Let’s see, what is coming up next? I’m in the middle of an album with the Strokes. We recorded the basic tracks here in Costa Rica, and they have to take full forms. I don’t know how long that’ll take. This is a new album with Kesha that I produced that’s very beautiful and different for her. That’s coming out, I think, soon. Those are the first two that come to mind.

COWEN: Great. Rick Rubin, thank you very much. Again, all listeners and readers, the new book is called The Creative Act: A Way of Being by Rick Rubin.

RUBIN: Thank you, sir.