Jessica Wade is a physicist at Imperial College London who, while spending her day working on special carbon-based materials that can be used as semiconductors, has spent her nights writing nearly 2,000 Wikipedia entries about underrepresented figures in science. That, along with numerous other forms of public engagement — including writing a children’s book about nanotechnology — is all in an effort to actually do something productive to correct gender and racial biases in STEM.

She joined Tyler to discuss if there are any useful gender stereotypes in science, distinguishing between productive and unproductive ways to encourage women in science, whether science Twitter is biased toward men, how AI will affect gender participation gaps, how Wikipedia should be improved, how she judges the effectiveness of her Wikipedia articles, how she’d improve science funding, her work on chiral materials and its near-term applications, whether writing a kid’s science book should be rewarded in academia, what she learned spending a year studying art in Florence, what she’ll do next, and more.

Watch the full conversation

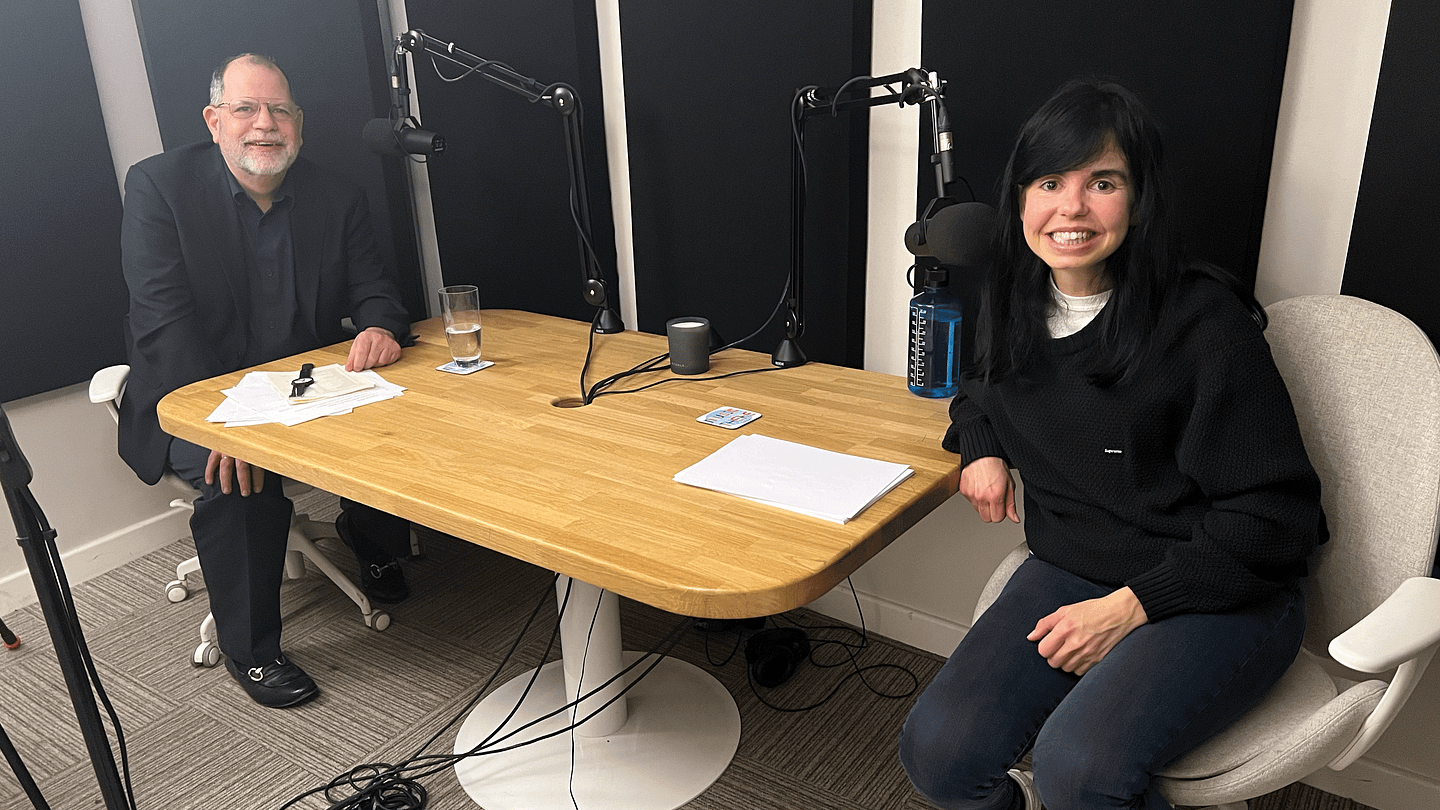

Recorded February 21st, 2023

Read the full transcript

TYLER COWEN: Hello, everyone, and welcome back to Conversations with Tyler. Today I am here in London with the great Jessica Wade. She is a researcher at Imperial College London, well known for her work in chiral materials and Raman spectroscopy. She has written a children’s book on nanotechnology called Nano. In the public eye, she is best of all known for having written over 1,900 Wikipedia entries as of February 2023. It will shortly be more, and those tend to focus on the history of women in science. Jessica, welcome.

JESSICA WADE: I’m so excited to be here. Hello.

COWEN: Let’s start with women in science. We will get to your research, but your writings — why is it that women in history were so successful in astronomy so early on, compared to other fields?

WADE: Oh, that’s such a hard question [laughs] and a fascinating one. When you look back at who was allowed to be a scientist in the past, at which type of woman was allowed to be a scientist, you were probably quite wealthy, and you either had a husband who was a scientist or a father who was a scientist. And you were probably allowed to interact with science at home, potentially in things like polishing the lenses that you might use on a telescope, or something like that.

Caroline Herschel was quite big on polishing the lenses that Herschel used to go out and look at and identify comets, and was so successful in identifying these comets that she wanted to publish herself and really struggled, as a woman, to be allowed to do that at the end of the 1800s, beginning of the 1900s. I think, actually, it was just that possibility to be able to access and do that science from home, to be able to set up in your beautiful dark-sky environment without the bright lights of a city and do it alongside your quite successful husband or father.

After astronomy, women got quite big in crystallography. There were a few absolutely incredible women crystallographers throughout the 1900s. Dorothy Hodgkin, Kathleen Lonsdale, Rosalind Franklin — people who really made that science possible. That was because they were provided entry into that, and the way that they were taught at school facilitated doing that kind of research. I find it fascinating they were allowed, but if only we’d had more, you could imagine what could have happened.

COWEN: So, household production you think is the key variable, plus the ability to be helped or trained by a father or husband?

WADE: Yes, house and that ability to be able to access it and do it, and the way that you’re taught at school and what you are taught at school. In the early 1900s — I can speak for the UK, but I’m sure it’s common around the world — women were taught science in a really big way, a much bigger way than they’re taught now in chemical sciences and physical sciences because men were learning Latin and Greek because that was recognized as important.

Then society realized women were getting really good at these things that could potentially have huge implications, pushed the women out and pushed the men back in, and you had this really big disconnect between what women wanted to do and could do, and then what they were allowed to do by society’s perspective.

COWEN: As late as the 1990s, one can read in quite serious science books the notion that maybe women were good at astronomy early on because women, more generally, are good at making careful observations. Should we regard that as an offensive stereotype or just giving women credit where credit is due? That kind of generalization — how do you look at it now from your vantage point in 2023?

WADE: I think those kinds of stereotypes aren’t very useful. I think it’s looking at the way that society has trained women to be, the words that they’re told, the advice that they’re given from a really young age, the way that they’re taught in school, the kind of support they get from their parents and teachers to pursue different subjects.

That associates particular personality traits with them that men probably have and do have just in equal measure, but because of the way that society nurtures and cultures us, we are pushed into these kinds of fields. So undoubtedly you might see more women in astronomy because of what society’s done, but it’s not a biological reason for that; it’s just a societal one. [laughs] I don’t even think you have to look back to the ’90s. You probably still find quite a few academics publishing on this now.

But if you design a scientific study destined that you want to be able to show that there’s some biological difference between men and women’s abilities, you’ll be able to design the study in such a way that you show that because you are so biased in the design of doing it.

If you go out and ask people and look at a general population without taking into account what society is doing, of course, you’re going to see these quite biased results at the end, and then you’ve already made your conclusion. I find those stereotypes not particularly useful. I’m very happy there are lots of women in astronomy. I wish we used those stereotypes about men as well, though.

COWEN: Are there any such stereotypes we should be willing to accept or even embrace? One reads also, well, Jane Goodall did better with chimpanzees because she was a woman. Maybe chimpanzees are more trusting of women. I have no idea. But all the stereotypes go, or just some?

WADE: Another fantastic question. I think probably the stereotypes about what it takes to be a great scientist or a great athlete or something like that — that hard work, that commitment, that dedication, that enthusiasm, that curiosity — I’m fine with those kinds of things. I don’t want people to be stereotyped by their gender or their ethnicity or their physical ability. I want everyone to have the same opportunity, and then to just be able to work out exactly what it is that they love and how they’re going to make the world better.

COWEN: How would you distinguish between productive and unproductive ways to encourage women in science?

WADE: I would say unproductive ways to encourage women in science, which happen a lot, is constantly telling women in science there aren’t any women in science. Constantly we’re told, “Oh, there’s only 8 percent women engineers, so come and be a woman engineer.” I don’t think that’s a particularly useful way.

I think the way to do it is to make sure everyone has the same educational opportunities. Make sure we have fantastic physics and math teachers in our high schools — and all our high schools, not just the expensive high schools. Make sure they’re getting the same kind of career advice and research opportunity. There’s quite a lot of evidence that shows that particularly people from historically excluded groups feel more like becoming a scientist if they’re introduced to the world of research and see those chances that they could have.

Then, we’re giving people the same support throughout their career. The same access to lab space, the same kind of access to scientific funding, mentorship — things like that. That’s really useful and productive. Telling women that they’re different or telling women that they have to become more like a man — “here’s 10 fantastic steps on how to give a great presentation,” like the power stance stuff — that’s not particularly helpful. But actually giving people that opportunity, that funding, that space, and that support — that is really helpful.

COWEN: As you know, science plays itself out in a lot of different venues. There are nonprofits, there are for-profits, there are universities, there are governments. On the whole, where has discrimination against women been least bad, and where has it been the worst across sectors?

WADE: I think probably it’s pretty bad across all sectors. I would say access to education and opportunities in education is, obviously, massively varied worldwide, but very challenging for women in particular parts of the world to access even basic education.

COWEN: Just say the West, so UK, US.

WADE: Okay. I don’t know, it’s such a big question. I think that if you look at the support women get throughout their careers in academia, the opportunities they get to build their own big research groups while simultaneously taking on caring responsibilities — because women still disproportionately get that in society — it is really challenging to succeed and be a really successful professor if you’re trying to do all of that other stuff as well.

Probably in financial sectors, in private sectors, you might get more flexible opportunities to return to work. I know that the pandemic has had a huge impact on the ability of women to come back to work because of the chance to work flexibly and things like that. Probably the private sector has done an awful lot of the work that academia and public civil service should be starting to do and is leading the way, but I don’t doubt that there are still huge discriminations and issues around sexism and racism within the private and the corporate sector as well.

Then government is a completely different issue because you don’t only have the internal politics of what’s going on and who gets promoted and who gets to be the public face, but also how the media is portraying those people, and the impact that that has on the general public’s perception of them. That’s obviously also extraordinarily sexist and racist and biased. Probably we should all be learning from what works well in the private sector — and also what doesn’t work — and trying to emulate that.

COWEN: If I think of 20th-century history from my naïve, distanced standpoint, it seems to me it was the commercial book market where women make a big breakthrough. You have Margaret Mead, you have Rachel Carson, you have Jane Goodall, which is what, 1971? The buyers of the books — they don’t seem to care, if the book is good or interesting to them. Then you have big advances for women in science that is led by for-profit incentives, basically.

WADE: That’s really interesting. I wonder if it’s still the same today. I wonder if people in that commercial book-market world would still celebrate and see the achievements of women scientists or the achievements of women, and take them as seriously as the achievements of men. I still get the feeling — despite you having a huge amount more writing and popular opinion around the need for more women scientists, or the work of women scientists, or the history of women scientists — it’s still a very specific type of person who will go into a bookshop and buy that.

Not every man who’s quite biased or opinionated on these issues will go and buy that fantastic history-of-women-scientists book even if they exist. I think booksellers and book marketers can do quite a lot of magic in that space, but we have to make sure it’s being read and exciting everyone.

COWEN: Now, you’re on Twitter, but my anecdotal impression is that social media, in general, have swung some of the bias back toward men, who, for whatever reasons, are more likely to be vocal on social media in terms of celebrity and science. Do you agree, disagree?

WADE: I think social media has been extraordinarily powerful for connecting people from groups where they are marginalized. People from historically excluded backgrounds coming together — potentially, they’re the one Black physicist in their institution, but they can come on social media and find a whole bunch of other Black physicists and get that confidence and that voice to be able to go out, give that amazing presentation, get that big research funding, and start doing their own thing.

Whilst I’m sure you’ve got the kind of cult of ego and these professors with their super labs and their lack of actual basic support for PhD students — and Twitter perpetuates that ego — actually, the magical parts of it, the magical parts of any of these social media, for me, is uniting people who before didn’t feel like they had a voice and saying, “There’s actually this amazing neuroscientist. If you go to Canada, you can meet and connect with them.”

People are changing their research fields. They’re changing their institutions where they work, and they’re really getting more opportunity. After the unjust murder of George Floyd, there was a huge outcry and support from the Black academic community to come together and to do more to support Black researchers. There were these movements set up: Black in Chemistry, Black in Physics, Black in Neuro.

They’ve galvanized a completely different change and approach to funding scientific research scholarships that have been made available. That’s happened within the last few years just because people came together on social media. So yes, there’s the egomaniacs, but then there’s also this kind of beautiful stuff happening as well, and I hope that that continues.

COWEN: How will artificial intelligence affect gender participation gaps?

WADE: I suppose it could affect it. I guess it depends, with all of these things, the data that the artificial intelligence is going to be trained on. You’ve seen it with ChatGPT, I suppose. I’m sure you’ve had a few conversations at university about how that’s going to change the way we have to set exams and get a lot more creative because these AI tools can now pass exams that you write. I think if you give the data in the correct way, potentially, it could give relevant advice.

I’ve seen it kind of hilariously . . . Some American scientific funding is now requiring EDI statements — I don’t know if you do yet — an equity, diversity, and inclusivity statement on a research proposal.

COWEN: Sure.

WADE: You can sit down — as someone like me who really cares about this a lot — and really harrow over how to articulate yourself in the word limit, and really think about all of the stuff that you’ve done and the stuff that you’re super passionate about, or you can just ask ChatGPT to write your own EDI statement. Actually, if the person who’s evaluating it at the other side can’t really tell the difference between the two, then someone who doesn’t care very much and can just run this through an AI-enabled language model can get the position when I can’t.

I think in that sense, it might make it really challenging to differentiate who’s actually passionate and who isn’t. Honestly, right now, I can’t think of any way that it will help it potentially —

COWEN: It could make it worse, possibly.

WADE: It could make it worse. You could use it in quite an effective way, I suppose. This is entirely in my head at the moment, so I don’t know if it’s what could be at all useful. But potentially, in allocating scientific funding so that it’s less biased — because at the moment, you have a bias about nationality, gender, institution — but if you asked an AI to learn from what has been a successful proposal before and what’s gone on to actually impact the world, and then use that and try to get it to assess science funding and who should get what, maybe it could be useful and less biased there. But again, it depends on the data that we’re feeding it.

COWEN: If ChatGPT can just reproduce these DEI statements, isn’t that an indictment of those statements?

WADE: Yes, it’s a complete one, but I think having them at all is an indictment of those statements because it’s almost like those ridiculous entrance exams that are used to go to medical school here or graduate school in America. If you’re privileged and surrounded by people who help you pass those exams, you get in. If you’re surrounded by people in your institution who can write your EDI statement, then it doesn’t mean that you care remotely about it; it just means you’ve got someone else to write it for you.

COWEN: In the United States, more than half of the graduating majors in the biological sciences are women, so there’s a lot of representation at lower levels. They may or may not go on. The percentage is much lower in a lot of the STEM fields. How much of that difference should we think of as resulting from just preference of the women?

WADE: We should think of it as resulting from preference as a result of what society’s nurtured them to think they are interested in, right? Because —

COWEN: But can’t some of it just be legitimate preference?

WADE: I don’t think it’s biological. I think it’s because of the way you were taught and introduced to it at school, or the passions and enthusiasms even of your parents. If you sit around your kitchen table every night, and you’re like, “Ah, mom, I’ve got physics and maths homework.” And your mom’s like, “I’ve always hated physics and maths,” then you, as a young woman, are like, “Oh, well, my mum hates it, so I’m going to hate it.”

Whereas boys, because they’re always taught that these are subjects that will give you huge opportunity and are really exciting, and all these successful men are going on to do them, they just do them anyway.

I think that you see it as being a preference because of the way that society and family has really centered around this fact that girls don’t study subjects like physics and engineering. Whereas if you gave them all the same opportunity, if we had amazing teachers in schools, if parents were a little less biased about the subjects they do and don’t find exciting, I think you’d just see that go.

In the UK, we have mandatory high school studying of chemistry to get in for medicine. If you want to go to medical school, you’ve got to do chemistry, and you’d probably do biology as well. As a result, chemistry undergraduate is gender balanced because girls start studying chemistry at high school, and they’re like, “This is an awesome subject, so I’ll go and do it at university.” If you made physics a mandatory subject for studying medicine, you’d have way more women studying physics undergraduate because they’d realize this is an awesome subject to do.

It’s much more about the advice we’re giving people rather than biological preference towards a particular subject.

COWEN: Is it 0 percent preference?

WADE: I’m pretty sure it’s 0 percent preference.

COWEN: What differences and preferences across men and women, on average, as groups, would you allow for?

WADE: What differences would I allow? Probably that —

COWEN: Men are more likely to be physically aggressive, more likely to be violent?

WADE: No.

COWEN: And that in no way maps into professions?

WADE: They’re larger and taller, and they can run faster. I think that the size [laughs] difference is probably the word. I don’t want to force anyone to study physics and engineering. I don’t want to force any man to do psychology and drama if he doesn’t want. But I do want a world where we stop telling people that because of their gender, they have some opportunity or some other opportunity. We just get to a point where we’re actually giving people the training and the support they need to go out and take on the challenges that the world is facing, and we get away from that kind of conversation. I don’t find it very useful at all.

COWEN: Wikipedia — by the time this episode is released, you’ll probably have written significant parts of over 2,000 Wikipedia pages. How should we improve Wikipedia?

WADE: I think Wikipedia is a phenomenal project. It started more than 20 years ago, at the beginning of the internet, this democratized platform for sharing information and knowledge. It’s a beautiful idea now. I can’t imagine Wikipedia working if you started it on this form of the internet.

It requires a huge input, a kind of public service from volunteers. Every single page on Wikipedia is written by a volunteer and expert in a particular thing, someone who’s fascinated by a part of history or a topic, and I really love it. It enables and it helps so much of society: teachers, politicians, academics, parents, everyone, home assistants.

COWEN: We put you in charge. How do you make it better? Or is it perfect? It can’t be perfect, right?

WADE: I think it’s a perfect vision. It’s a perfect idea. From working in universities, we have so much access to knowledge, largely taxpayer-funded access to knowledge that people don’t have, so we do have this responsibility to take that information and give it to them.

Unfortunately, Wikipedia does have huge gaps in its content because of the types of people who edit it. So, because you’ve got a relatively small group of people who edit Wikipedia a lot, doing this huge public service in creating content, the majority of them are men. The majority of them are from the Northern Hemisphere; they’re mainly men from North America. You have certain gaps in the type of content that’s on there, particularly in biographies of women. Anything to do with current science is quite badly written about on Wikipedia because lots of academics don’t see it as a good time investment.

If I was going to change Wikipedia for the better, not that I think it — well, I do think it could be a little bit better — I would work on improving those content gaps. I’d work on really saying we need more academic people to start contributing their time to editing this. You know what it’s like working in a university, getting people to want to teach and not just do their research all the time. Actually, we need to focus on this public service act of giving people access to knowledge.

But we really need to start rectifying some of these content gaps about the global south, about emerging science, fixing pages about climate so that we provide nonpartisan information to lots of people, but also on detailing the contributions of women to all aspects of society. I focus on science and engineering, but there are women doing awesome things in casting and movies and in writing, and I think we need to start telling their stories too.

COWEN: What if I said something like the following hypothesis? Autistic people very much enjoy organizing information. Males are much more likely to be autistic than women. Autistic people therefore really like Wikipedia, so it’s no surprise it’s a matter of preference that there are so many male editors on Wikipedia. That’s a kind of scientific claim, right? It could be true. Maybe it’s even likely to be true. Or not?

WADE: I think before we test that side, we should probably get data. I think there’s probably a huge number of autistic women who would say that, actually, it’s just very underdiagnosed in women because they socially assimilate to take on the very virtues or the stereotypes that you, as a woman, have to have as a young person in society. So, they put a blanket over issues of autism. But I’m not going to go there because I’m not an expert, but I think that’s what they’d say.

Actually, I think everyone gets excited about this contribution to open knowledge. I’ve written a bunch of Wikipedia pages, but I’ve also trained a lot of people in how to edit Wikipedia, from young people in high schools to academics at universities to members of the general public. And they find it awesome, this idea that you can research something, pull together all of these different sources, maybe do some kind of history aspect and go through archives, and then write something that’s actually on the internet.

If you tell a high school kid who’s used to writing papers that sit in a desk and then eventually get shredded, “You’re going to write something that the whole world will see,” everyone gets excited about that, irrespective of their gender or of their ethnicity. I think we should do the study. We should get the data and try and find out how many Wikipedia editors are autistic.

But more, just creating this ecosystem where people who get this opportunity to learn and find out awesome facts also feel that social responsibility to give that back and give that access to everyone else in the world. Because maybe Wikipedia isn’t so important in North America or Europe, where we have free and open access to a lot of literature or a lot of texts, or we have popular-science publishing, but in other parts of the world where they don’t have access to that, actually having Wikipedia is completely critical.

I wish we’d get away from this kind of blame. It’s just like the women scientists thing. A lot of people get angry that these kinds of topics aren’t on Wikipedia. Instead of getting angry, I think you should just do something about it. It takes nothing to contribute and to edit and to learn how to edit. Everyone should sit there and give everyone in the world this access to the knowledge that they have.

COWEN: Will GPT models take significant market share from Wikipedia? Because if you type in the name of an obscure female — or just an obscure scientist — into ChatGPT or its successors, it’ll give you a lot of information. It’s not perfect, but actually, the more obscure the person, the more likely it is to be accurate.

WADE: I don’t think it will take away from Wikipedia. I think the beautiful thing about Wikipedia is you can interrogate it quite a lot. You can see who wrote what, when they wrote it, and when that reference was added, what that reference is. You have that kind of talk or dialogue behind a Wikipedia page. Most people just land on the read aspect of Wikipedia, but if you go to history or go to talk — the tabs across the top — then you see what was contributed to and when, and you have a discussion around what is and isn’t on the page.

I think things like ChatGPT are very useful at giving you a very quick answer, or if you were looking up a person and said, “Make me a short PowerPoint on this,” it might give you that starting-off point from which you go on and find out more things.

But I think the ability to interrogate it and to look at — again, coming back to my earlier points really, where it looked for that information. Has it been broad in where it’s collected that from? Is it using actual appropriate citations and literature? You can’t do that. Wikipedia is still important for showing people this person really did the homework on pulling this very nonbiased page together, and that’s why you can trust it.

COWEN: You can keep on interrogating GPT models, but does it at all induce you to rethink what you’re doing? Because obscurity per se is no longer the barrier. Literally everything, everyone is in ChatGPT in some sense.

WADE: The beautiful thing, I think, about Wikipedia is that when I land on Wikipedia, I don’t usually go on it to type in the name of a woman scientist — I do that a lot — but one doesn’t go on it and type in the name of a woman scientist. One goes on it and types in “climate change” or “number theory” or some kind of thing that they’re interested in, or the name of their high school or their university, and then they look through the alumni, or they’re just clicking around and they find their way to this page.

I love that, the kind of sleuth, stealthy parts. You’re saying these women are here, or these Black scientists are here, or these scientists from Africa are here, and you’ve just not found out about them yet, but they’re learning about it because of the topic that they’re interested in.

I worry that if you have something like ChatGPT, and you go on and you ask it one of these questions, like, “Tell me about number theory,” it will just give you the answer about that and, potentially, the few big men names in the field. But you’d miss that chance to do that kind of beautiful weaving that you do around Wikipedia, that bouncing around things before you land on that page about that woman scientist. So I don’t think that my work here is entirely futile just yet.

Actually, part of what Wikipedia has really shown me is, women are just not getting enough awards for science, so I spend a lot of my time not only researching these people, but also writing citations for people to become fellows or get big awards and medals and honors. I think I can keep doing that even if ChatGPT takes over my evening job of editing Wikipedia pages.

COWEN: If I think of my own work, typically I prefer not to know, say, how many people listen to a particular episode of the podcast or read a particular blog post. It’s better not to know. You write all these Wikipedia pages — there’s no obvious means of feedback where you know how effective you are. Do you like it that way? Or do you wish you had a way of measuring the efficacy of your output?

WADE: I think sometimes it’s useful. You can get pageviews. Sometimes that’s useful as a motivator for why people care about it.

COWEN: So, you can get page views.

WADE: Yes, you can. I don’t look at them because — [laughs]

COWEN: Because you prefer not to know?

WADE: Well, I prefer not to know, but also that’s not why I’m doing it. I just want these stories there. But sometimes, if I’m trying to get, particularly academics, excited about editing and I’m like, “Well, there’s 15 billion people who look at this every month, and we did this Wikipedia edit last time, and a million people have already looked at the pages.” Then they’re like, “Well, I’m going to go on and write about the science I do, then.”

The thing I find amazing isn’t the kind of Wikipedia data in the numbers that come back, but seeing how these people are then celebrated in the public eye. There is a phenomenal mathematician that I wrote about, called Gladys West, who is 91 now. Born in Virginia, went to a historically Black college and university, studied maths, became a high school teacher for maths before working for the US government and doing the calculations that enabled GPS. She worked out how far from a perfect sphere the surface of the earth was so that they could put satellites around it and help us with navigation.

When I wrote about Gladys West, it was the beginning of my Wiki editing world. It was 2018, and there was very little about her online. She was 90. She’d done all these things in the ’60s and ’70s, and she is an extraordinary woman, but very little about her, and really little honoring her and celebrating her. Now her Wikipedia page is up. She’s in all of these lists of top women in the world. She’s been inducted into the US Air Force Hall of Fame. She’s won a medal from the Royal Academy of Engineering. Every time I see people talking about GPS, they’re like, “Yes, Dr. Gladys West, mathematician, enabled this.”

I don’t want the metric from Wikipedia that tells me how many times that’s been viewed. I want society to be like, “Look at this cool, awesome woman, or this cool, awesome scientist of color.” Now we’re starting to celebrate them. I like that. I guess it’s enabled by Wikipedia that the world is starting to honor them.

COWEN: A lot of the problems of science funding, I think, stem from the fact that bureaucracies ossify over time and once-dynamic institutions become just very difficult to work with. Should we expect the same to happen with Wikipedia? Which, of course, is a nonprofit.

WADE: I think it’s interesting. I don’t know if you’ve had Wikipedia people on the podcast.

COWEN: Jimmy Wales, of course. He was a great episode.

WADE: Okay. He’s just the coolest, isn’t he? He’s so cool. Fangirl, massively. I’m going to listen to that also on the way home.

I do think that you’ve got an extraordinary culture in the Wikimedia Foundation, the people who facilitate Wikipedia. They’re very global. There are only about 200 people who actually work for the Wikimedia Foundation. They’re very young, they’re very enthusiastic about open source, they’re very forward-thinking in what this encyclopedia should be, and they’re always pushing boundaries, changing the interface, changing the graphic design — all of these different things to make the user experience better and the editor experience better.

I think that from that nature — because you’ll have this push from the actual employees — we just need to do that part, as the community that Wikipedia is serving, to make sure that the editorship represents the kind of global community who read Wikipedia. I think if we keep pushing for that, then it doesn’t have to ossify and become backwards and archaic. We can keep progressing for something that’s more fair and equal and representative for everyone.

COWEN: Your own research — you’ll be able to explain all of it for us. There are four concepts I want to put on the table: chiral materials, Raman spectroscopy, nanotech, and quantum computing. What you do relates to all of those four, right?

WADE: I hope so. I hope so on the quantum part. It’s quite exciting.

COWEN: Let’s start with chiral materials. Tell us what that is.

WADE: Chiral materials, because it underpins everything else.

COWEN: We’re going to go through all four, and then you’ll tie it all together for us.

WADE: Okay. Very nicely, very succinctly. I work on functional molecular materials, so carbon-based materials that can be semiconductors. Semiconductors are obviously hugely useful for any kind of optical or electronic device — solar panels, light-emitting diodes. The chirality part is that these molecules can exist in these beautiful and weird and wonderful forms, but they can also exist as non-superimposable mirror images of one another. That’s what chiral is.

A great example is your left and your right hand. If you put them together palm to palm, they’re mirror images, but if you put one on top of the other, they’re quite clearly not. We see that non-superimposable, mirror-image nature across multiple different-length scales in the human-made and the naturally occurring world.

You see it in electrons and photons. You’ll remember from chemistry, you had spin-up and spin-down electrons. You drew out a little up-and-down arrow. You see it in left- and right-handed light, light that twists clockwise and counterclockwise. We see it in molecules, and we see chirality in things like shells, in snail shells, in wisteria barks. You see that twist that’s clockwise or anti-clockwise.

COWEN: There’s a reason for that, right? It’s endogenous to something.

WADE: Well, naturally occurring life — all DNA in human life or in plant life or anything on planet Earth — is right-handed. All sugars are right-handed. All amino acids are left-handed. There’s some reason that that happens, that life selects for that. We still don’t know the reason that that’s the case. It’s the fascination of a lot of scientists.

COWEN: Do you have a hypothesis?

WADE: Well, there’s one that comes back to the quantum part at the end. These molecules that I work with are chiral molecules. They’re molecules where . . . well, some of them that I work with are just helices that are twisted structures where you connect these benzene rings together. Because of the ways they’re connected, they can’t lie flat in a plane, so they twist up or twist down.

What I was trying to do with them — particularly for electronic devices — is use that chirality, that shape, to control the polarization of light that comes out. If I’ve got this emissive chiral molecule, a molecule that will emit light, and it’s twisted clockwise or anti-clockwise, can we make the light that comes out left- or right-handed slightly polarized? That’s really useful for display technologies because it means you can double the brightness that you get and reduce the power consumed. From a technological advantage point, that’s very exciting, just from a photon side.

What’s emerging for the reason for homochirality of life on Earth is that not only do they emit twisted lights, but they also transport up or down electrons. Depending on whether you have a left- or a right-handed molecule, you’ll get a preference for up electrons passing through the system with ease or passing through the system with difficulty.

COWEN: So, it’s more efficient transportation with chirality?

WADE: Depending on the handedness of the molecule and the spin of the electron, which is quite revolutionary from trying to control not only charged transport but spin, which would enable a whole bunch of new technologies involving aspects of quantum. But people are trying to push, within the chirality community, that this could also explain the reason for homochirality of life on planet Earth. Because electron transport is much more efficient if you already have these electrons moving only in one direction, and they’re pushed through by the shape of the structure.

Lots of things, like chlorophyll, are chiral. Lots of these forms that you have — proteins are chiral. It’s that shape, that very structure, to enable this efficient electron transport that makes life on planet Earth happen more smoothly. There are various theories of that. I’m not sure how much I’m on board with them yet.

COWEN: Part of the program here is to use these insights to build new semiconductors — taking that term rather broadly — which are based on different materials and they’re more flexible. That’s the end goal?

WADE: That’s the end goal. Not only giving you this new flexibility, so that carbon-based, lightweight, easy-to-process, relatively low environmental impact — much less so than the semiconductors we use at the moment — but also that you get these new functionalities, like generating really twisted lights or generating really highly spin-polarized electrons. That can enable you to go out and do things that are more useful for the kinds of technologies we’re creating.

If you could create some kind of chiral molecular-thin film that, at room temperature, could spin-filter electrons, can that enable some kind of quantum tech thing to happen much more efficiently without the huge infrastructure that we need, at the moment, to enable and to enlarge these quantum properties so we don’t have to do it at cryogenic temperatures?

We don’t have to have extraordinary pressurized compartments to be able to do this. We can just do it on a benchtop with some kind of molecular material. That’s the end goal, not only to take a technology that already exists and say, “Hey, we can do it more efficiently,” but give it new functionalities that we couldn’t before, by controlling the shape of the molecule.

COWEN: So, there’s even a possibility — maybe speculative — there could be biological semiconductors, broadly construed, even biological parts of quantum computers. Am I mishearing you?

WADE: There’s a part where we learn from biology and could use it in some kind of quantum realm. We’d learn from something like DNA. We’d learn from the topology of DNA, this chiral shape, and we’d use it to filter electron spin or to detect photon spin, and then we’d use that to enable some kind of quantum sensor. Definitely that.

COWEN: It wouldn’t all have to be super cold if it works.

WADE: No, it won’t have to be super cold. That’s a very exciting thing. If it works, if we can systematically produce these chiral structures in a really ordered and beautiful way, but also if we do the science to get it exactly right and have the theory behind what’s going on at the moment, that’s huge excitement because people have these experimental results, and they’re like, “Whoa, let’s go and change the world.”

But their backup theory for why these processes are happening — it’s still not there. It’s still not got a universal agreement. I think molecules will provide us a whole bunch of new opportunity in quantum that we’ve never seen before.

COWEN: The spectroscopy part of what you do — spectroscopes — you can use them to judge if food is rotten, if a painting is authentic, if something is an explosive. What do you use them to do?

WADE: Spectroscopy is a huge, encompassing, and wonderful term, as you just illuminated in those examples. Basically, normally spectroscopy is, you shine a light on something and you see what light is transmitted through or reflected from it, and you work out what that thing is because you’re looking at the electronic structure.

Raman spectroscopy, which is the type that I’m particularly excited about — and you can use it on paintings — is a vibrational spectroscopy. Instead of looking at electronic energy levels, we’re looking at vibrational energy levels.

Long story short, you shine a laser on a molecule or on a material or on a painting. You make all of the bonds — the chemical bonds within that structure — start to vibrate. If there’s a carbon-carbon stretch, that will start to vibrate and do these weird and wonderful stretches. Then that, as a result of that vibration, scatters the light that goes back at a slightly different energy to the light that you shone on it.

You get this Raman spectrum, we call it, but you get a spectrum, which is an extraordinary and molecular fingerprint of all of the different chemical bonds within your structure and how they’re arranged and ordered with respect to one another.

I can then take my molecule or take my material, put it under this laser, find out exactly what’s there, but also how ordered and arranged these things are. If I’m trying to make something for a quantum application, I want them to be super well-ordered and super well-oriented. I can’t ask the molecules what they’re doing. They’re way too small to see with an optical microscope, but I can use this vibrational spectroscopy to work out exactly what’s going on, and I can do it in situ. I can find out what’s happening when I apply a charge to it or heat it up. So you can work out a huge amount just from this interaction with light.

Raman spectroscopy — I love it because it’s so versatile. My friend — we did our PhDs together. He did Raman spectroscopy for solar panels, originally. He’s called Joby, I should say. He then went to work for NASA on the Mars 2020 mission, doing the Raman spectroscopy for the SHERLOC instrument, which is on the Mars rover, which is out there at the moment, collecting data from Mars and looking at the organic signatures from their Raman spectra.

He’s now in the Natural History Museum, looking at microplastics that are found in birds that are washed up on the beach, using spectroscopic Raman signatures of their exact molecular packing and confirmation. It’s just this technique that takes you to all of these wonderful places, centered around this amazing vibrational effect which we can’t see. It just seems like magic to me, which I really love.

COWEN: This could make nanotech more effective, possibly.

WADE: It’s actually a really fantastic and perfect point. We use it, at the moment, to optimize the way we process these materials. I’ve got an amazing chemist who’s made this beautiful molecule. I want to turn it into a thin film to put into a device. I’ll work out exactly how to do that really efficiently by doing some microscopy, but doing a lot of the spectroscopy to work out, how do I perfect the recipe to put it into that device?

If we could do that kind of in-line, in-manufacturing processes, which you do a bit in inorganic semiconductor industry, then you’d have this really efficient way of creating a technology where you know every single time, this is what the molecules are doing, and that’s how we’re going to put it in. I’m sure they do it in display manufacturers already, but that’s how I envisage it.

COWEN: Let’s say this research program goes fairly well, not utopian well, but say 90th-percentile well. Thirty years from now, what will we see or what will I use or what will I have that will be the result of this? Or is it 50 years? How do you think about that stuff?

WADE: I think five years from now — or probably even less because display manufacturers are so extraordinarily quick at the way that they innovate — you’ll see chiral molecules being the active layer of your LED display. If you’ve got an Apple iPhone, or I think Nintendo Switch has an OLED display, or if you’ve got a massive OLED television at home, you could double the efficiency of those displays by just using something that emits circularly polarized light.

We’re working on that a bunch in academic research, but display manufacturers are on that too. So in five years, you’ll have that, and your power consumption — you will only see it in that your battery won’t be drained as quickly because you won’t be pushing all of this power into generating light from a pixel, which isn’t very efficient, because you’ll have increased that efficiency.

Probably 10 years from now, you’ll see quantum technologies that are enabled by molecules, and particularly by using the topology and the shape of those molecules to make them more efficient, that can do this room-temperature operation. And probably chirality will have some big role to play in that.

But like with all areas of science and all areas of any academic aspect that we’re studying — and probably lots of conversations you’ve had around these tables — there’s a lot of jargon, there’s a lot of words. Chirality is an important and useful word for me. It means a lot of different things to people in the quantum world. You can have chiral electrons, you can have chiral phonons. Probably it will be hugely important, but what particular aspects of chirality, I’m not entirely sure yet.

COWEN: But in terms of a new item — we can make screens better; we can make batteries last longer — maybe it’s too early to say, but what new good or service could we expect? Again, assuming things go fairly well.

WADE: I think a lot around optical communications and encrypting data transfer and things like that. If you can harness circular polarizations of lights, you can multiplex the way you send data. You can make use of left- and right-handed channels, but you can also encrypt the signal that you’re sending because only the sender and the receiver know what to expect, based on the kind of chirality of those patterns that are produced.

Probably, in some kind of encrypted optical communications, you’ll see this, but again, not know entirely that that’s what’s happening. But making more efficient and more impactful technologies like that, we will entirely have.

The particular aspect that I’m really excited about at the moment, other than all the other work I do — because I love everything I do — but it’s trying to use chiral structures to be able to detect really weak magnetic fields, particularly the magnetic fields associated with brain function.

When neurons are sending signals around your brain, they generate these tiny magnetic fields. If you could use some kind of chiral structure to be able to detect those magnetic fields optically, you could generate some kind of medical imaging system that was much more flexible. Again, it could operate at room temperature. I think you’ll see innovations in things like medical imaging, and also in optical communications.

COWEN: Now, I can pick up popular science magazines, and they will tell me, sometimes, we have quantum computing now. How accurate is that?

WADE: Well, I think you’ve got some kind of systems with a very primitive number of qubits that can do some calculations, these quantum bits. They can do some kind of mathematical calculations much more efficiently and quickly than their nonquantum counterparts. I think getting enough — and I’m really not an expert in this — but getting enough of those qubits to work in harmony to actually do anything that’s computationally useful for you or me is way, way off where people are currently at.

At the moment still — and I’m not sure if you’ve visited any labs that are doing this or any companies that are doing this — but they have these isolated molecules trapped in vacuum chambers, or they have these cryogenic chambers where they’ve got a hundred different qubits in a room the size of a football stadium, each there trying to connect and interact with each other. I think that’s a long way away from what we can imagine happening in our own personal homes or in our companies or in our lives.

Whilst people have demonstrated that quantum computation is possible, we’re really, really far away from it being societally relevant or useful. And maybe we don’t need it right now for the types of things that we’re going to need to do.

COWEN: Let’s say we put you in charge of science funding in the UK.

WADE: Thanks.

COWEN: You’re a dictator, in essence.

[laughter]

COWEN: Apart from the question of how much should be spent — because scientists will always want more spent, but put that aside — for any given level of funding, how would you change the system?

WADE: I would probably try and shift the narrative at the moment from judging people based on their résumé or their previous track record. We have a huge amount of institutional bias in the UK. If you work in a few universities, you’re much more likely to get science funding than if you work in others.

If you are judging people based on their résumé, which we do — we submit our CV, we call them — and also our research proposal. People often look at the CV first, check where you work, check if you’ve had career gaps, check all of these things that they’re quite biased about, and that impacts their likelihood to fund your science.

The DFG, the German Research Council, quite progressively, a few years ago, flipped it so they no longer got people to check the résumé and just evaluated based on the proposal of the research. It was much more democratic and fair and gender-balanced because you didn’t have that bias creeping in that. I’d change that.

COWEN: More fair, more balanced — does it give better outcomes?

WADE: People are just as innovative, just as creative, and just as wonderful at doing the science. There was a really interesting paper recently that looked at the impact of institutional privilege on generating the number of science papers. It wasn’t that people were making more breakthroughs; it’s just that they had more opportunities to make those breakthroughs because you’d given them so much money to be able to do it. So, I’d get people to judge based on the research that was being proposed, and the infrastructure or support that they’ll get to be able to do it.

I’d also think we probably need to have . . . I think this is starting to happen. We have a national quantum technologies program here. There needs to be a really serious look about how we create materials and technologies that are actually going to benefit society and not just be these things that we have to cryogenically cool or do in extraordinary vacuum chambers. Get a little bit more creative and forward-looking at looking at new molecular materials and thinking about these new challenges to make sure that we make these technologies.

From a very personal . . . I’m not being very responsible for everyone else working on materials — I’d say we need to invest more in molecular materials. But I’d also say we need to get rid of these biases. Things like making sure everyone has equal opportunity to prepare for interview, making sure everyone has equal opportunity to put the time into writing a proposal. I wrote a bunch of proposals last year, which completely exhausted me, but it would take a month to write this perfect science proposal.

COWEN: Sure, but isn’t that totally wrong? Shouldn’t we make the proposals three pages?

WADE: We should make the proposals three pages, and we should make sure everyone has the same support to be able to write those. You can be —

COWEN: But that will just up the requirement. Why not take away the support and just impose a three-page maximum? Nothing else is considered. Attach a PDF, but it won’t be read. Wouldn’t that be better?

WADE: Well, again, then we’re just going to favor the people who are in places or have this prior history of writing these things and can write these savvy three-page proposals. We need to give people the support to be able to write them. Something I’ve seen a lot, not only on trying to improve things for celebrating women scientists, but it’s just this complete inequality and access inequity in the way that we give people support and access.

This hidden curriculum in academia has a huge influence on the type of science that we fund. Sure, reduce the page count. I had to write something recently for an American funder where they were like, “Just write 20 pages.” I was like, “What do you mean, just write 20 pages?” Definitely reduce the page count, but I think beyond that, we need to make sure everyone’s getting the same opportunity to write those perfect three pages. Because at the moment, we don’t, which is why we see biases in what’s coming out and who’s being funded.

COWEN: Stuart Buck has argued we should fund basically people, not projects, in most areas. The Arc Institute in California, connected to Stanford, has more or less that approach. Do you agree, disagree?

WADE: I think it can be absolutely fantastic and transformative, especially in things that are clinically relevant. Having these amazing institutes where you’ve got clinicians working with basic research scientists and computer scientists and analysts — fantastic. I would say we’re still at risk there of creating these little empires, where certain people get huge amounts of scientific funding, and other people don’t have that opportunity and that seat at the table. So sure, fund people, but make sure that we’re representing an equal and fair in the decisions of who we fund.

COWEN: But isn’t fairness overrated in the sense that there’s meritocracy and there’s fairness, and there’s some tension between the two? Why always side with fairness?

WADE: Because I don’t think we’re getting the most disruptive or exciting scientific ideas at the moment from just funding the few big people who’ve always had science funding. I can think of a few people in the UK who consistently get big research grants, and I don’t think their labs are producing massively innovative or exciting stuff. They just consistently have this money thrown at them.

So, I would say the pursuit of fairness is because we want science that is exciting and impactful, and at the moment, we’re not seeing that. We’re just seeing the same people get huge multimillion-pound grants.

COWEN: What did you learn writing a children’s book about nanoscience?

WADE: That children’s publishers don’t want you to write a whole book for a six-year-old about vibrational spectroscopy.

[laughter]

WADE: It was just a huge opportunity to be able to write it. It made me very proud to do what I do. I absolutely love being a scientist, and I think I know that, and then you write it down and you’re like, “This is the coolest job in the world.”

But also, we don’t do enough to get young people and parents excited about material science and chemistry. You go into a bookstore, and all of the books for kids are about dinosaurs or about space or gross things about the human body. But they’re not like, “Here’s amazing materials that you can use as a solar panel, or potentially will become a quantum computer one day.”

It made me think a lot more about our responsibility as people who work in materials of going out and talking about these things to young people. The public response to it has been absolutely extraordinary. I thought, nonfiction hardback kids’ book, [laughs] so it’s a really hard sell.

Luckily, it was illustrated by a phenomenal woman, Melissa Castrillon, who’s got this beautiful, whimsical approach to illustration. It was her first nonfiction book, and when she was asked to do it by the publisher, all of her illustration friends were like, “Don’t do it. Nanotechnology will be so dry.” [laughs] But I’m very glad she did it because it’s completely beautiful, and that’s probably helped get people into reading it.

It’s been translated into all of these different languages. It’s got all these stars, these American literary guilds, these library prizes, which I never dreamed possible. But I think it’s just because materials are really exciting, and I had to do no work to make that book exciting. She did some to make it beautiful, but I think it’s just shown me people in the world want to read about this.

COWEN: Again, to our listeners, the title is Nano by Jessica Wade. Should academia reward that kind of project more than it does right now? Which is either zero or negative as far as I can tell.

WADE: Yes, zero or negative is right. I think that’s —

COWEN: Probably negative.

WADE: A lot of people are like, “Oh, she’s not very serious about the science she does because she does this.” I think that academia should reward anything that is taking the science or the outcomes of their research to a bigger audience, whether it’s something like going out and giving public lectures, whether it’s something like doing a kids’ book — that’s fantastic.

COWEN: Is there a way to fix that without de-emphasizing peer review?

WADE: [laughs] Yes, right. My peer review is the editors. I think some institutions are a lot better at that than others. Some institutions in the UK, a lot of institutions in the US will recognize that public service aspect of what you do in promotion and in recruitment, and they’ll see it as something that’s really positive. I can think of a few absolutely phenomenal professors who have really incredible research programs and some very public-facing aspect of their work, or some people who work on really huge, innovative parts of reforming education.

We have less of that in the UK to what you have in America. You could shift it a little bit. We’re trying to, at the moment. One of our big funding councils has made fellowships where 20 percent of your time can be on something like policy or like looking at equity, diversity, and inclusion. It’s starting to happen.

But I still love all the other parts of my job. I love being in the lab, and I absolutely love teaching undergraduates. I didn’t write this book because I wanted academia to be like, “Oh, children’s books are really valuable.” But it is interesting because I’ve had so many emails afterwards from academics who are like, “I’m thinking of writing a kids’ book, too. Can you give me some advice about this?” So, obviously, a lot of people are thinking about it.

COWEN: You’re a junior person there, and you’re now the most famous person there in your field. Does that create an imbalance with your colleagues? Or do they just not know, they’re in too much of a fog?

WADE: [laughs] I’m definitely not the most famous person.

COWEN: You are the most famous person in your field there, I will predict.

WADE: There are a lot of very awesome people there. I don’t know, it comes back to that earlier point about it being negative. People think of you and judge you just for that, and so you have to constantly be doing this awesome science as well, and they’re like, “Oh, actually, they are a serious scientist.” You’ve always got to prove them wrong, so you definitely have that.

Whether they dislike me because of it, I’ll find out soon enough. I’m currently on one of those awful — you know how UK funding works. I’m on a fellowship which is like a year and a half more funding, and so let’s see. If everyone’s going to push me out for writing this, then more power to another institution that gets me. [laughs]

COWEN: What did you learn in your year of studying art in Florence?

WADE: Well, I tried to learn a lot of Italian. I was very lucky to have a landlady who was a professor of history of art at a university in Florence and only spoke Italian, and I spoke no Italian and was very junior. Also, you get this extraordinary perspective — which you do whenever you’re in Italy — about how extraordinarily interdisciplinary and multitalented these Renaissance masters were. They were —

COWEN: Obsessed with materials, right?

WADE: Obsessed with materials, obsessed with innovative new techniques for painting, for architecture, for building buildings that you can’t feasibly imagine working without a computer or without a huge infrastructure to be able to make it happen. The metallurgy of the doors, the woodwork, the beautiful glass nanoparticles being used long before we’d be able to study and call them nanoparticles — you really learn that this idea that everything has to be in silos, that scientists are distinct from artists or craftspeople, was completely gone then.

In Renaissance Italy, they just didn’t have that. You had to do everything. Then you go into high schools now, and you have to choose whether you’re going to do the sciences or the arts. You have to choose whether you’re going to study physics or whether you’re going to study art. It taught me a lot more about that.

I obviously always knew creativity was very important for being a good scientist because if I’m going to design an experiment no one’s ever done or explain something in a way no one’s ever explained it, you have to be quite creative to do that. But you get it so much reinforced when you are in Italy, and particularly in Florence, that before, people could do this a lot, and they didn’t talk about it all the time. They just did it.

Similarly, though, they also didn’t recognize the contributions of women, and there’s almost no . . . Artemisia Gentileschi is one of the only women Renaissance artists or women artists that the world —

COWEN: That’s a bit later, too.

WADE: That is a bit later than when all of this stuff was happening, and she also had a really hard time to get to being where she was. You saw this idea of the polymath. This idea that people could do science and art perfectly well was celebrated, but society still didn’t value women.

COWEN: Last two questions. First, what is your most unusual successful work habit?

WADE: Unusual successful work habit. I suppose it has to be the Wikipedia editing. I go into the lab or teach or whatever research proposal I’m writing every day. Then I go home, and after dinner, I edit Wikipedia. Part of it is this advocacy. I really want these people to be celebrated and to be honored.

But I also get this huge chance to learn new things every single night that are out of the little bubble that I’m in of learning about chirality and how that influences technology. I learn about a cool new spectroscopy or a cool new university I’ve never heard of or what people are doing for this particular type of technique, and then that opens my ideas and perspectives for something else.

Actually, as a scientist and as a material scientist, I am very interested in new materials and new ways to study them. I’m always going around the world trying to do experiments with cool and interesting people, and one of the best ways to prepare for going to do that experiment is to write the Wikipedia page of who you’re going to be with.

I was, last week, at this High Magnetic Field Lab in France, getting this opportunity to do solid-state NMR, so to do nuclear magnetic resonance, but of thin films and materials. And it’s completely fascinating, another one of these weird and wonderful, magical scientific techniques. But just writing the biography of the person I was going to work with meant that I was really prepped for going. And if I’m about to see someone speak, writing their biography before means I get this. That’s definitely my best work habit — write the Wikipedia page of what it is that you are working on.

[laughter]

COWEN: Final question, what will you do next?

WADE: What will I do next? I really, really want to make it in academia. Not just because I love the science, but also because I really like this idea that you can try and do these little incremental changes to make it better for the next generation of scientists. Whether that’s making scientific funding more equitable, whether that’s really shifting how we teach to make sure that we’re teaching in a way that’s preparing this group of researchers to go out and change the world.

Not just teaching because it’s what someone’s curriculum was 10 years ago, but saying this is really exciting, and this is what we want you to learn about now. You are in the university, you’ve connected, you’ve checked in, you want to be here. Let’s do it, too. The transformative education, the research, and also this progressive idea of making it more fair and equal. I want to stick around in academia to make that happen.

COWEN: Jessica Wade, thank you very much.

WADE: Thanks so much for having me.