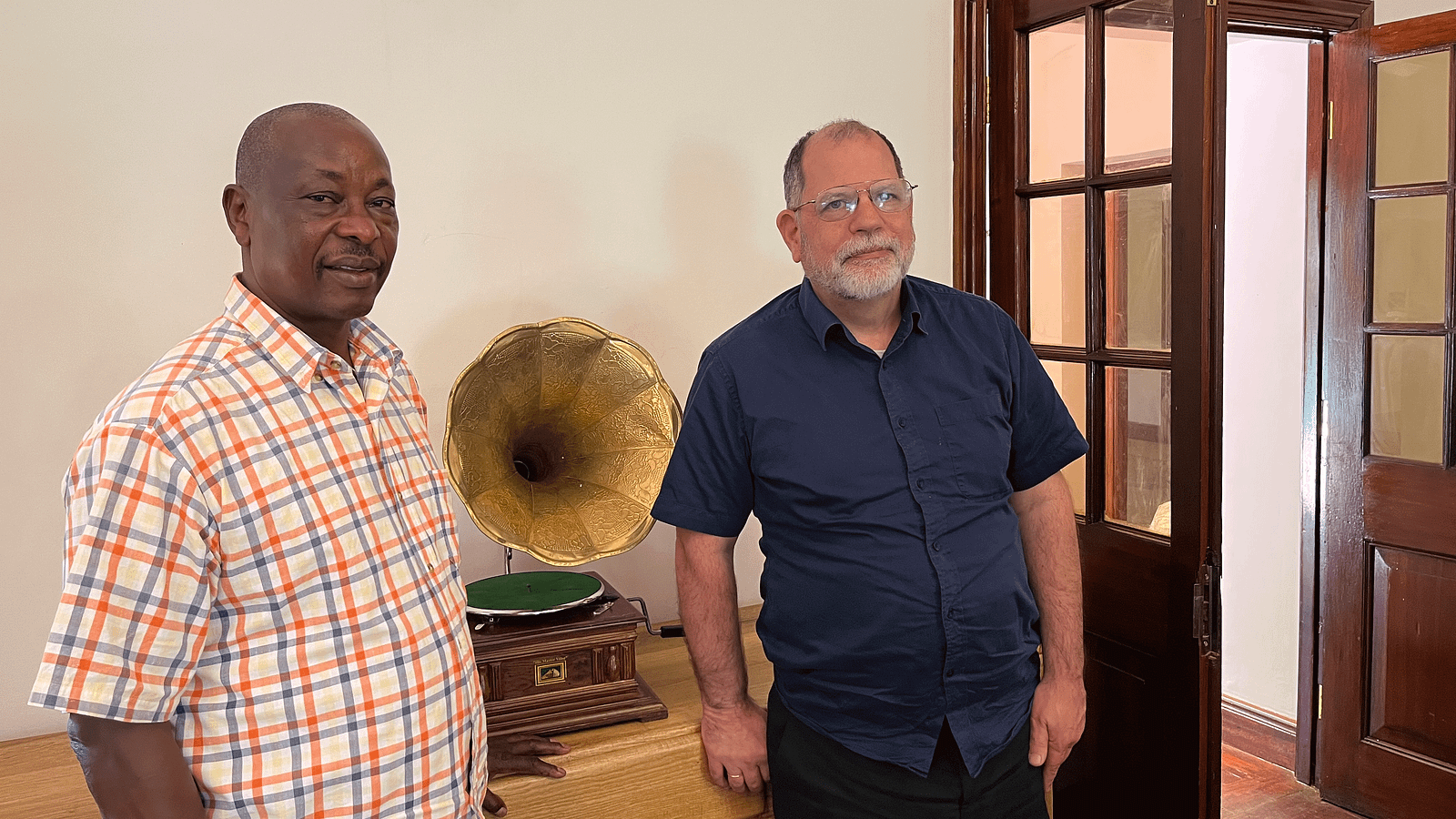

As a follow-up to the episode featuring Stephen Jennings, we’re releasing two bonus conversations showing the daily life, culture, and politics of Nairobi and Kenya at large. This second installment features Githae Githinji, a Kikuyu elder and businessman working in Tatu City, a massive mixed-used development spearheaded by Jennings. Born in 1958 and raised in a rural village, he relocated to seek opportunities in the Nairobi area where he built up a successful transportation company over decades. As a respected chairman of the local Kikuyu councils, Githae resolves disputes through mediation and seeks to pass on traditions to the youth.

In his conversation with Tyler, Githae discusses his work as a businessman in the transport industry and what he looks for when hiring drivers, the reasons he moved from his rural hometown to the city and his perspectives on urban vs rural living, Kikuyu cultural practices, his role as a community elder resolving disputes through both discussion and social pressure, the challenges Kenya faces, his call for more foreign investment to create local jobs, how generational attitudes differ, the role of religion and Githae’s Catholic faith, perspectives on Chinese involvement in Kenya and openness to foreigners, thoughts on the devolution of power to Kenyan counties, his favorite wildlife, why he’s optimistic about Kenya’s future despite current difficulties, and more.

Watch the full conversation

Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or your favorite podcast app to be notified when a new episode releases.

Recorded June 12th, 2023

Read the full transcript

TYLER COWEN: Hello, everyone, and welcome back to Conversations with Tyler. Today I’m sitting here in Tatu City, right outside of Nairobi, Kenya, and I’ll be chatting with Githae Githinji. He’s a businessman in the transport industry, and he’s a Kikuyu elder. He’s stationed at Tatu City, where he’s a chairman. His roles as chairman include dispute resolution and also coordinating community ceremonies.

His most recent activity as the elders’ chairman for the area around Tatu City was planning and coordinating the cleansing ceremony of a Mugumo tree being moved into Tatu City. Gitahi is 58 years old. He is from the Agikuyu community. He is born and raised in Mukurweini, Nyeri County, the central region of Kenya. He resides now in Kiambu County, where he has also established his business. Githae, welcome.

GITHAE GITHINJI: Welcome also.

COWEN: Thank you for talking with me.

GITHINJI: Yes.

COWEN: What is your business? Could you tell us?

GITHINJI: I deal with transports.

COWEN: Transports. What does that mean specifically?

GITHINJI: I have matatus, and I have small vehicles which I normally deliver for commercial purposes.

COWEN: You own the vehicles. You sell them to businesses, to individuals, or who are your customers?

GITHINJI: No, I do transport. Let’s say transporting people from Ruiru to Nairobi.

COWEN: You drive them from one place to another?

GITHINJI: I don’t. I own.

COWEN: I see.

GITHINJI: So I employ people who do that job. I manage my business.

COWEN: When you look for good drivers who will do good work, what qualities do you look for in them?

GITHINJI: A driver who is competent in what he’s doing.

COWEN: How do you tell if they’re good? When you talk to them, you have an interview, what do you ask? Or how do you approach that?

GITHINJI: Normally, I do test them, me personally, see whether somebody has all the requirements to be a driver — you need to have all the documents that are required by the government — and then his ability to do that job.

COWEN: How can you tell who will be a good driver or not a good driver?

GITHINJI: It’s a person who is qualified in that skill.

COWEN: So, the main thing is the license.

GITHINJI: The main thing is the license, plus the other government documents and whether somebody is sober.

COWEN: Sober?

GITHINJI: Yes. Sober, I mean, you can’t employ some others who are drunkards, who can cause lot of things. You have to look for somebody who is a little bit educated, who knows responsibility. Or a person who can handle that vehicle itself.

COWEN: Yes, I understand. The part of Kenya where you’re from, that’s Mukurweini, right?

GITHINJI: Yes.

COWEN: What is special about that part of Kenya?

GITHINJI: The part of Kenya, Mukurweini, well, as I could say, I left the place a long time ago. The moment I finished my school, I came here to Ruiru, and that’s why I established myself here in Ruiru. I left my motherland.

COWEN: Why did you leave there?

GITHINJI: I was just coming to look for good pastures here.

COWEN: Just for better jobs?

GITHINJI: Yes. When I came here, I was employed here. When I got employed here, I invested here. I got a piece of plot here, on which I built, so I reside here now.

COWEN: Where you come from, do you miss it in any way, or you’re just happier to be here?

GITHINJI: No, I just go there visiting.

COWEN: Just visiting.

GITHINJI: Even though I lost my mother and father, I just go and visit my brothers who are there.

COWEN: Why do you think you left and they didn’t? What’s the difference?

GITHINJI: That is a rural area. We don’t have a lot of job opportunities like we have here in Kiambu or in Nairobi.

COWEN: Even apart from jobs, if you just think about living there, is it more exciting to live here or more interesting to live there?

GITHINJI: Well, I would say it’s more interesting to live here because if I may think of job opportunities, or looking for something, here it’s more convenient. More than the rural area.

COWEN: Your native language from the family is Kiswahili, right?

GITHINJI: Yes.

COWEN: You learned English here, or you learned it in school?

GITHINJI: Kiswahili?

COWEN: No, but that [Kiswahili] you grew up speaking, right?

GITHINJI: I grew up speaking Kikuyu.

COWEN: Kikuyu. Okay.

GITHINJI: Yes, Kikuyu is my main language.

COWEN: What other languages do you speak?

GITHINJI: The other language is Kiswahili.

COWEN: Yes, and English, of course.

GITHINJI: English, eventually.

COWEN: How did you learn those?

GITHINJI: From school.

COWEN: When you were growing up as a boy?

GITHINJI: Yes, when I was growing as a young boy. I went up to Form 4 [last year of secondary school].

COWEN: If you think about Africa as a whole, do you think you’re lucky to live in Kenya, or you wish you were somewhere else? Or how do you view Kenya within Africa?

GITHINJI: Kenya is a good country.

COWEN: What makes it good?

GITHINJI: It makes it good for — actually, the way I have stayed here, I’ve never seen bad things.

COWEN: In terms of violence or disorder?

GITHINJI: There’s no violence. People here are very peaceful.

COWEN: You think the economy is pretty good for Africa?

GITHINJI: Well, I would say it’s good.

COWEN: How did you come to have your role in Tatu City?

GITHINJI: In Tatu City, where I reside is just near the Tatu City area. As the community, we just have groupings where we go and you are shown how Kikuyus . . . Our tradition, we normally do enjoin and have our own ways of conducting our own selves. I joined those wazees [elders] and I was initiated to that group. I became so active to an extent that even then, they felt the role I’m playing to them, I need to be their elder and they chose me as the chairman.

COWEN: Okay, I understand. What makes you good at that? What’s your quality that makes you a good elder?

GITHINJI: It’s because of knowing how to coordinate people in the best way. If you are a violent man, I just come, I talk with you in a polite way, we understand one another. I show you how you are supposed to live with the other people. I show you the goodness of peace and such kind of things.

COWEN: It’s a lot of experience dealing with people.

GITHINJI: Yes.

COWEN: What would be a typical dispute that you have to decide or resolve?

GITHINJI: A lot of them.

COWEN: What would be an example? What might happen where they need you?

GITHINJI: Example?

COWEN: Yes.

GITHINJI: Let’s say if there’s a fight between a man and a man, if there’s a person who have, let’s say, got somebody’s property, such kind of things, we sit down, talk it out. Somebody shooting the other, domestic violence, all of that.

COWEN: What do you do that the court system does not do? Because you’re not police, but still you do something useful.

GITHINJI: What we normally do, we as a group, we listen to one another very much. When one person reaches that stage of being told that you are a man now, you normally have to respect your elder. Those people do respect me. When I call you, when I tell you “Come and we’ll talk it out,” with my group, you cannot say you cannot come, because if you do, we normally discipline somebody. Not by beating, we just remove you from our group. When we isolate you from our group, you’ll feel that is not fair for you. You come back and say — and apologize. We take you back into the group.

COWEN: If you’re isolated, you can’t be friends with those people anymore.

GITHINJI: When we isolate you, we mean you are not allowed to interact in any way.

COWEN: Any way.

GITHINJI: Any business, anything with the other community [members]. If it is so, definitely, you have to be a loser, because you might be needing one of those people to help you in business or something of the sort. When you are isolated, this man tells you, “No. Go and cleanse yourself first with that group.”

COWEN: Does your family reject you also, or just your friends?

GITHINJI: If your family rejects you, that is a family dispute. If it comes to that, we take it in another way, because we have to know first, how does that dispute arise? It might be that your wife is the one who has a problem. For that, we don’t interfere so much. We leave it to the family.

COWEN: If the man has the problem?

GITHINJI: If the family has a problem also, we chip in and we help them to resolve that dispute.

COWEN: By talking to both of them.

GITHINJI: Yes.

COWEN: Talking to get them to agree again.

GITHINJI: Talking to both of the parties. Yes.

COWEN: What’s the biggest family problem that you see? The most common one.

GITHINJI: The most common one is, it happens when one man is so drunk, [he] beats the woman, chases the woman, or the woman pushes with other men. Let’s call it adultery. When she does that, at least we do normally chip in to resolve that issue, but [it’s] not [the] most common. That one, we normally leave it to the family. Not unless the family comes to us and tells us, “We need help in this.” We normally don’t like so much interfering in the family matters.

COWEN: Problems with children? You deal with those, or not so much?

GITHINJI: In form of children, yes, we normally do, because in our group as men, we initiate small boys from childhood to adulthood. We circumcise. When you reach the age, we have groupings where we circumcise all Kikuyu boys. Kikuyu, Embu, boys from Meru. GEMA, that is our community. We call it GEMA community, the group of that community. We do have groups where we have our own doctors, qualified doctors.

Let’s say, like last year, we had one in Githunguri, here in Githunguri Primary School. That is where we were. We had 350 boys whom we initiated. We help them, we call them, we talk with them, tell them the rite of passage that one person is going [through], educate them, and after that, we stay with those boys for 10 days.

COWEN: 10 days?

GITHINJI: Until that boy is healed.

COWEN: How old is the boy at this point?

GITHINJI: At this point is when he finishes Standard 8 [last year of upper primary school].

COWEN: Okay.

GITHINJI: While now he’s going to Form 1 [first year of secondary school]. We make sure we mentor that boy. At the same time, after the boy goes back to the parents, the following year, we make sure we prepare a seminar. We call them [the parents], because we do normally follow them up to see whether this boy has good behaviors or whatever. If he tries to be misbehaved, let’s say, [drinking] beer and the rest, we talk to that boy. We make sure that we are molding somebody who can be able to come and join the community.

COWEN: There’s a ceremony surrounding this initiation? Are there parties, or people get together, or how does that work?

GITHINJI: What happens, we have the doctors who initiate the boy, and we have old men coordinated by me, if it’s in my area that I’m the chairman [of] now. They are the wazees who talk with these children. Show them how to live and whatever.

COWEN: If there was a problem you could fix in your community, one thing you could improve, what would it be?

GITHINJI: What I would wish very much, for example, like you people, when you come to this place, just try to help us, the area people. Try to come, bonding [with] these people, because you have come, you got these people. If you bond with them, we also welcome you as our brother, which is so good.

COWEN: Kikuyu people in Kenya, do you think they’re different from the other groups, or the culture is different? How would you describe that?

GITHINJI: All the groups have their own culture. If it’s Kikuyu, they have their own. If it’s Luos, they have their own. This is something that we met. It is not something that we are creating. It is from our old grand-grandfathers.

COWEN: How would you describe what is special about Kikuyu culture?

GITHINJI: What I would describe about them, they are good. That is one thing. I’m not saying they are good because I’m a Kikuyu. I’m saying [it] because they are hardworking people.

COWEN: Many people say they’re very good at business.

GITHINJI: They are friendly and good businesspeople. Yes. They are business minded. They are not lazy people.

COWEN: Not lazy. Do you think they’re more extroverted, more open?

GITHINJI: More than. Even if you go to any part of this country, there’s nowhere you can go and don’t find a Kikuyu. If you move from here to Mombasa, you will get a lot of Kikuyus. If you go everywhere, Kikuyus are always there. They like interacting with the other communities.

COWEN: The way marriage works for Kikuyu, is it different from the other groups?

GITHINJI: Marriage?

COWEN: Marriage, courtship, how you decide whom to marry, the ceremony, everything. Is it the same or different?

GITHINJI: There’s no difference, because we also marry other communities. A Kikuyu is allowed to marry a Kamba. Yes, we intermarry with those communities.

COWEN: You marry at the same age, younger, older, or that’s all the same?

GITHINJI: It depends on the feeling of that one person. You can marry whomever you want. Yes, you are free. We don’t have limitations, that you should marry this, or that, or that, but we do not encourage old men to marry small children.

COWEN: Sure. Of course not.

GITHINJI: That’s not good.

COWEN: How many children do you think a typical family wants to have now? In Nairobi?

GITHINJI: In Nairobi, mostly as I can see, now these young people are preferring two, three.

COWEN: Two or three.

GITHINJI: In our times, in our old wazees, like in my family, my father had eight.

COWEN: Eight?

GITHINJI: Yes.

COWEN: Which do you think is better?

GITHINJI: According to today’s economy, I would say we don’t much get 10 children, which you won’t be able to look at after. It is better you have three or four, whom you know very well, you are going to cater to them until their adulthood.

COWEN: There were some countries where families just have one. Is that weird to you? You go to Korea, people have, on average, about one. A little less, actually.

GITHINJI: Average of one is not good, because accidents do normally happen.

COWEN: Sure.

GITHINJI: If you have one child, and he dies, you are left with nothing. Why? Get two or three. In the case of anything, you are left with something. If you have one and he dies, and you are old, you cannot get another one. Do you see, you’d be left like that?

COWEN: Yes. Children here, do they take good care of their parents and grandparents?

GITHINJI: Yes, they do it. They do.

COWEN: That’s expected? It’s part of the culture.

GITHINJI: It is this, but we don’t force them to. It will depend on your relationship between your children and you, your own self. Because there are some men or women who do not care for their children. They just get the children, and they let them go away. It’s good to interact with children. Show them you are their father, show them you are their mother. These children will give back. The way you bring up children is the way they will also give back to you.

COWEN: Today, the grandparents, do they help bring up the children, even if there’s only two?

GITHINJI: Yes.

COWEN: They still do?

GITHINJI: Yes.

COWEN: What if the family has moved to Nairobi, moved to Mombasa, and the grandparents are far away? How do things work?

GITHINJI: For us Kikuyus, if somebody lives far, we do normally meet. Let’s say, during the holidays, you make sure you go home, you enjoy it with them.

COWEN: How do you get home? You take a bus?

GITHINJI: You take a bus, or if you have means, you have a vehicle, you just go there.

COWEN: Just drive? Yes.

GITHINJI: Yes, drive, stay with your family for at least two or three days, then you go back to your job.

COWEN: Now, I have read in the newspapers, the cost of living in Kenya is much higher now than a few years ago.

GITHINJI: It is.

COWEN: Why did that happen?

GITHINJI: I don’t know whether it’s because of the population. I don’t know whether it’s because of the development we have here. Actually, for that one, I cannot tell you the . . . But it’s because of . . . We have a high — what do we call it? Let’s say, if you look in one way or another, the climate has changed. When the climate has changed, we don’t have enough food. Do you get me, right? When we don’t have enough food, you expect that life has to be harder, because there are some people who depend on the rain. Do you get me, right?

From that, if you go to, let’s say, to a place like in Nairobi right now, as we are living, the cost of living also is so high. Cost. Let me talk about the sector I’m in: transportation. Life is very hard because of the increase of petroleum. Because, if I could say, the price of petrol is too high, and I cannot be able to hike the price for the person whom I’m carrying, because these people don’t have money. I have to dig deeper into my pocket to sustain what is being added in the petrol [price].

COWEN: What do you think should be done to change things because it costs so much?

GITHINJI: What needs to be done is now . . . That is now up to the government now, to know how they are going to look at their people. Yes, because we now, we are tied up.

COWEN: Do you know what should be changed to improve this thing?

GITHINJI: Because, one, if we say the climate, that is up to God now. We have to pray to God now to give us good rains. Like this year we had good rains. What we could do is, we know why we are not having enough rain.

COWEN: Why?

GITHINJI: We plant a lot of trees. We stop logging. We plant a lot of trees so that we could get enough rain. When we go back to the side of the government now, the government — it’s for them to know how they’re going to regularize these prices, so that at least life should be a little bit . . . Yes.

COWEN: Do you use mobile money to buy things? Money in your smartphone?

GITHINJI: Yes.

COWEN: How does that work for you? That’s easy, that’s hard, or how is it?

GITHINJI: It is not hard. It’s easy, because when we get money, nowadays we even use phones when we are paying things. It’s better because we don’t lose a lot of money when we use, even though there’s a lot of tax in it.

COWEN: Do you order things online? You buy online and someone sends it to you?

GITHINJI: No, for me I don’t.

COWEN: Younger people do, or?

GITHINJI: Young people do.

COWEN: What kind of things do they buy online?

GITHINJI: Oh, normally they buy things that they don’t have — you don’t have here.

COWEN: Things from other countries.

GITHINJI: From other countries, like vehicles, kitchen wares and whatever, even building materials. They do normally do it.

COWEN: Why don’t you buy online?

GITHINJI: Me, I’m a little bit analog.

[laughter]

COWEN: Do you listen to YouTube at all?

GITHINJI: It’s rarely.

COWEN: What do you listen to?

GITHINJI: The common radio.

COWEN: Common radio?

GITHINJI: Yes.

COWEN: What kind of music? Banga music, or you listen to Congo music?

GITHINJI: Traditional music.

COWEN: Traditional?

GITHINJI: Our traditional music, yes.

COWEN: What kind of traditional? Kikuyu?

GITHINJI: I like the Kikuyu or Luo music, whichever. I like those very much.

COWEN: This will be on the radio. Do you like music from other African countries?

GITHINJI: Definitely, yes.

COWEN: What else do you like?

GITHINJI: Oh, you are talking of?

COWEN: What you like. Yes, Nigeria. There’s a lot of Nigerian music in America now.

GITHINJI: All countries.

COWEN: All countries?

GITHINJI: Yes, the only thing the music should . . . Whichever music, if it’s good. [chuckles]

COWEN: Do you listen to any American music?

GITHINJI: If it chances to be on the air, I do.

COWEN: You do?

GITHINJI: Yes.

COWEN: What do you listen to?

GITHINJI: Whichever music is being . . .

COWEN: Whichever is playing on the radio?

GITHINJI: Yes.

COWEN: You have public utilities, right? You get electricity, water. How good are those services?

GITHINJI: The services that we are being given by . . .

COWEN: That you get. Your electricity, is it reliable?

GITHINJI: Yes, it is. It is.

COWEN: And your water?

GITHINJI: Even the water, we have enough water.

COWEN: You have enough water?

GITHINJI: Yes, from these boreholes. We are getting water from these.

COWEN: You get water from a well, or from piping, or how does your water come?

GITHINJI: Let’s say in our area, this area we have now, we have people who supply water from wells, and also from the county government.

COWEN: Yes, and you feel that’s safe water?

GITHINJI: We could say it’s safe because what they normally do when we get this water, they treat it so that we can consume it.

COWEN: What are some of the other expenses for a family in Kenya? There’s food, transportation, rent. What else is a big problem?

GITHINJI: Education.

COWEN: Education?

GITHINJI: Yes.

COWEN: If you send your kid to school, the kid is 10, the school is free, or you have to pay?

GITHINJI: You have to pay.

COWEN: Even for government school?

GITHINJI: In government [schools], you also have to pay, but little money. Yes.

COWEN: You think the schools are good?

GITHINJI: I would say it’s good because I’m used to those schools. We don’t have more, but we can’t say they’re better than those. You normally adapt what you see or what you get there.

COWEN: Funerals, do they cost a lot of money?

GITHINJI: Now, for the funeral, it depends on the family. Because for the funeral, if the family feels they’re going to buy an expensive hearse or coffin, it’s on them. That one depends on how the family is, because there are some who don’t require a lot of money; there are some who like to use a lot of money. That one will normally depend on how the family is.

COWEN: The family pays for everything, or the community shares the cost?

GITHINJI: Most of the times for the funerals, the communities chip in.

COWEN: Who decides how much people pay?

GITHINJI: Nobody decides. You give what you have. You are not being forced to, “You have to give this.” No.

COWEN: People who have more money, they give more money?

GITHINJI: Definitely, yes.

COWEN: Do you ever have disputes over this that you have to judge?

GITHINJI: No.

COWEN: Because they always agree?

GITHINJI: Yes.

COWEN: I’m surprised they always agree. In my country, they would not always agree.

GITHINJI: I don’t know why. In this country of ours, we don’t do it like that.

COWEN: If you could change something about the government in Kenya, what would you change? What’s the biggest problem?

GITHINJI: If I could?

COWEN: You could change something about government here. They would do something new, stop doing something bad, change some law. What would you change?

GITHINJI: For that one, I couldn’t say. There’s nothing I can or cannot change, because I depend with what my government tells me to do.

COWEN: Yes. So, there’s nothing you can change?

GITHINJI: Not unless the government comes in and tells me, “Change this and change this.” They are our leaders, and we have elected them, so we have to follow what they tell us to do.

COWEN: Sometimes, do you wish they would tell you different things?

GITHINJI: We, as elders, we don’t dispute with the governments.

COWEN: You don’t dispute?

GITHINJI: Yes, we don’t.

COWEN: You help enforce it in a way, right?

GITHINJI: We don’t force them to do things, we depend on what they tell us.

COWEN: Women’s rights movements in Kenya: Do you see a lot of that? Feminism, bigger role for women, more women working?

GITHINJI: For women, let’s say, I can’t talk much, even though they have their own rights.

COWEN: What do you think of feminism in Kenya? That women should work, have equal say as the men, have more rights?

GITHINJI: No, no, no, we are all equal here.

COWEN: All equal.

GITHINJI: Women have their rights, and we do have our own rights.

COWEN: Yes. So, you think women have equal rights already?

GITHINJI: Even though when we come to our community, there are some stages that we limit. You cannot expect a woman to be in control in a manly home. No.

COWEN: In government, how many women are there?

GITHINJI: That one I can’t say.

COWEN: The president is not a woman, right?

GITHINJI: Yes.

COWEN: People in the legislature, there are mostly men?

GITHINJI: No, even women. We created another . . . Let’s say, in the Senate we have women reps, so that they could bring that, the gender [ratio], to be almost the same.

COWEN: How was it here during times of COVID? Was it a big change, or not so much?

GITHINJI: By then life was too hard, because that was something that we were not used to. We had a very hard time.

COWEN: Things closed down, or everything stayed open?

GITHINJI: Things closed down. We had to stay indoors. There was a lot of curfew. The times that you needed to work, you were told, “No, you can’t go.”

COWEN: How many people got COVID?

GITHINJI: Actually, I cannot tell you the actual figure, but a lot of people.

COWEN: Did you?

GITHINJI: No, I didn’t.

COWEN: You were lucky?

GITHINJI: Let’s say, it was God, because I also went for the vaccination. I took the medication, so I thought . . .

COWEN: You took the vaccine?

GITHINJI: Yes, I did.

COWEN: Most people did here?

GITHINJI: Yes.

COWEN: Which vaccine was it? Chinese, American, do you know? British?

GITHINJI: They were all. The people were taking all.

COWEN: All?

GITHINJI: Yes.

COWEN: Do you know which one you had?

GITHINJI: I can’t remember, actually.

COWEN: How was it to stay at home for so long? Was that hard?

GITHINJI: It was hard. It was tough, because you cannot expect being told at once, “Stay at home,” and you are not used to it. It was too hard.

COWEN: Yes, I think it was very hard in many places.

GITHINJI: Yes, and we lost a lot.

COWEN: A lot of people died.

GITHINJI: Even economically, we lost a lot. I think that time of COVID is the one that brought even these hardships we have even today. We have not yet returned to our normal because of that period.

COWEN: How much do you worry about crime? People stealing things from you. Is crime a big problem for you, or do you feel it’s very safe?

GITHINJI: Some time back, let’s say in two or three years ago, there were a lot of crimes, but nowadays, the government has tried to regularize the crime in these areas of ours.

COWEN: With more police, or what do they do?

GITHINJI: Not even more police: Also involving the community. The government decided to introduce this thing we call Nyumba Kumi. When it was introduced, the Nyumba Kumi, if they noted there was somebody who was not good in that family, they had to report to the nearest so that that person could be dealt with. It did help a lot. At the same time, they also used the wazees and whatever in the community to identify all these thugs and whatever.

COWEN: You think crime will keep on getting better in Kenya?

GITHINJI: Yes.

COWEN: For this reason?

GITHINJI: Yes.

COWEN: Why do you think crime is worse in Nairobi than in smaller cities?

GITHINJI: Definitely, you expect because the life in town is harsher than in the rural areas.

COWEN: It’s just tougher to live there.

GITHINJI: Yes.

COWEN: Costs are higher, you need more money.

GITHINJI: In town you need money, and when you need money and don’t have a job, you expect yourself to drive yourself to such kind of things.

COWEN: What do you think is the biggest problem in the slums? If you go to, what, Majengo, one of the slums?

GITHINJI: Employment.

COWEN: Employment. So, not enough good jobs?

GITHINJI: Yes.

COWEN: Future jobs for Kenya, what do you think they will be?

GITHINJI: The future jobs in Kenya? That’s what I was saying, if we could have people who can help in getting us good jobs and whatever, trying to help these young people get jobs, I think we could just minimize these kind of hardships that these young boys get.

COWEN: When President Obama visited Kenya, I think it was 2015, did you care? Were you excited? You don’t care? What do you think?

GITHINJI: Well, for such a person visiting here, everybody was excited because it was even being told that his roots are in Kenya. We were happy about that man coming to visit us. We see our brother who has gone somewhere and become a great person.

COWEN: He’s still very popular here.

GITHINJI: Yes, more than. He is popular.

COWEN: The Kenyans who move to America, what do people think of them? They’re happy, or they view them as totally different now? What’s the image?

GITHINJI: For that one I can’t say much because I’ve never visited that area.

COWEN: You haven’t been to America, but people talk about those who leave, right?

GITHINJI: At the same time, I don’t have a relative who has been there.

COWEN: How about Kenyans who go to England?

GITHINJI: Actually, they normally say when they go there they get good, the place is good, or such kind of a thing.

COWEN: Do you think they’re happier, or do you think they’re happier here? The ones who leave?

GITHINJI: Definitely, that one I cannot answer because, I told you, I have never had a relative who can talk one on one and tell me.

COWEN: There was a change in the constitution of Kenya. It gave a lot more power to the counties, right? Was that a good idea?

GITHINJI: Yes, it was a good idea because the help that the government used to give the community, when it was devolved to the people, it became so nearer to the people, more than when it was in the national government. Because if there is anything like development and whatever, that money is in the counties. It’s easier for the governor to deal with this work than it was in the national government, yes.

COWEN: I’m sure you know many foreigners come here to see safari, to see animals, elephants. Do you care about these animals? Are you excited, or you’ve seen so many it’s just ordinary for you? What’s your attitude?

GITHINJI: We do care about [them], because it is even a boost for us for the revenue. When new people come, we ship in something.

COWEN: We spend money here.

GITHINJI: Yes, you spend money here, and our economy is boosted a little bit.

COWEN: If you see an elephant, you personally, are you excited? Or do you say, “Oh, I’ve seen a thousand elephants. I don’t care.”

GITHINJI: I’m also excited because we are not mostly used to it. The things that cannot excite me is this thing you are living with here time and again. Let’s say something like a dog, a cat, domestic things. We cannot be excited for such kind of things. But when you go get a leopard there, at least you have to be excited.

COWEN: Which animal excites you the most to see?

GITHINJI: Who, me?

COWEN: You. Hippo?

GITHINJI: Something like a lion. [laughs]

COWEN: Lion?

GITHINJI: Yes, because I’m not used to it so much.

COWEN: The lions — if you see one, are you afraid? Or maybe they’re afraid of you.

GITHINJI: You have to be afraid because you have the experience that if it chances to get you, it’s going to eat you.

COWEN: Do you ever go on a safari as a guide? Or do you go to Maasai Mara to see the animals?

GITHINJI: Well, I normally don’t, because in my area in Nyeri, I just see these animals openly there.

COWEN: You just see them normally. You don’t need to go anywhere.

GITHINJI: There’s no point of going to all that much spending, and I could see them on my way home.

COWEN: Have you seen leopard? Many people say leopard is hard to see.

GITHINJI: Yes, I do. In our area, we have those leopards.

COWEN: You see all the different birds in your area, or many of them?

GITHINJI: Yes. I do see them.

COWEN: Is that interesting to you, the birds?

GITHINJI: It is not that much interesting because I’m used to them.

COWEN: What do you think is the attitude here towards China, Chinese people? Do you think they’re welcome, or there’s prejudice, or?

GITHINJI: Well, what we normally do here in our country, if somebody is coming to help us, then you expect us to be friendly with that person, but if somebody’s coming to bring problems with that, we’d say, “No, that’s not a good person.”

COWEN: You think China has helped Kenya overall?

GITHINJI: Well, I could say yes, because they have come to help our young boys. When they come to do the roads and whatever, they employ our young boys and whatever, who are unemployed.

COWEN: They build roads, they build buildings, and that’s good for people.

GITHINJI: Yes.

COWEN: Does America help you at all?

GITHINJI: They also do.

COWEN: What do we do to help?

GITHINJI: Because when they come and start their projects or whatever — when, let’s say, we see these people, like these who came to Tatu City, they’re also helping us because they come and we get these industries here. These industries — they employ our youth, which is a boost to living here.

COWEN: Are there groups of people who come who don’t help? Who make things worse?

GITHINJI: I couldn’t say so, because I’ve not gone to that study so much.

COWEN: Do you worry about Kenya’s neighbors? You have a border with Ethiopia, but there’s been a big war in Ethiopia. Do you worry this will affect Kenya? Somalia, right?

GITHINJI: I do worry, but definitely, I can do nothing, because we don’t know why those people are fighting. They have their own domestic things there. I prefer to mind my own.

COWEN: If you help them with dispute resolution, do you think you could improve it for them?

GITHINJI: If it can be, if we can do that, it’s good. We can help them if we can. If we can reach there and be able to help with disputes and whatever, it’s good. It is always good to have friendly ties and get your neighbor without a lot of vitas [war] and whatever, fighting and whatever. It’s good to have a good neighbor.

COWEN: Yes. A lot of people from India live in Kenya, of course. They’ve lived here maybe 100 years, the families. Do you think of them as Kenyan, or do you think still it’s like different? You think they’re Indian?

GITHINJI: What I believe, if you come here — let’s say, you come here, and you acquire property here, if you get a child when you are here, I would say that child is a Kenyan. You’re not supposed to be chased by anybody. You have decided to come. You’re also a human being. I believe I can go and live anywhere as long as I’m accommodated there.

COWEN: Do you like Indian food?

GITHINJI: I wouldn’t say whether I like it or not because I’ve never . . .

COWEN: You don’t eat it.

GITHINJI: I don’t eat it. I’ve never [crosstalk] . . .

COWEN: You eat ugali, Kenyan food.

GITHINJI: Yes, I’m used to my normal food.

COWEN: You like ugali?

GITHINJI: More than.

COWEN: What else do you eat? For a normal meal, what else do you eat, besides ugali?

GITHINJI: Nyama choma.

COWEN: What is that?

GITHINJI: Nyama choma? Nyama choma, it is the meat we slaughter from our goats and whatever.

COWEN: Does goat meat here have a special or sacred status? Is it the best meat?

GITHINJI: Well, I would say yes, because when we are doing our sacrifices, we men, we Kikuyu, we normally use those goats, those lambs.

COWEN: That’s your favorite food?

GITHINJI: Not really.

COWEN: What’s your favorite?

GITHINJI: Vegetables.

COWEN: What kind?

GITHINJI: At my age I don’t prefer eating a lot of meat so much. I prefer taking these local foods.

COWEN: What kinds of vegetables might you have here?

GITHINJI: Here?

COWEN: Yes, that you eat.

GITHINJI: We do have a lot of them.

COWEN: What would you eat? A normal meal?

GITHINJI: Definitely, yes. I do.

COWEN: The young people, do they eat the same things you eat, or they eat very different things?

GITHINJI: Young people prefer taking these junk foods. Those from the supermarkets, chips and whatever, of which is not really good for them. They should eat the foods that we wazees eat that can live longer and live a little bit healthier.

COWEN: Are you religious? Do you go to church?

GITHINJI: Yes, I do.

COWEN: Christian, or Muslim, or?

GITHINJI: I’m a Christian.

COWEN: Christian. What kind? Protestant?

GITHINJI: No, I’m a Catholic.

COWEN: Catholic.

GITHINJI: Yes.

COWEN: What about Catholic is more appealing to you?

GITHINJI: I was brought up a Catholic, from my childhood, and I came to like it, because Catholics are not all that much controversial.

COWEN: Being religious, does that help your work as community elder?

GITHINJI: Yes.

COWEN: How does that relate? How does it connect?

GITHINJI: When you are near to God, you are near to people also.

COWEN: The people respect you more?

GITHINJI: More than.

COWEN: You think the religion gives you some wisdom?

GITHINJI: Yes.

COWEN: Do you watch TV at all?

GITHINJI: I do.

COWEN: What do you watch?

GITHINJI: Local things.

COWEN: Like movies, or news, or just everything?

GITHINJI: I’m not much of — movies, not so much.

COWEN: What language do you watch in? Kikuyu or English or?

GITHINJI: Any.

COWEN: Any?

GITHINJI: Yes.

COWEN: Whatever’s on.

GITHINJI: Yes.

COWEN: Do you like foreign shows, or do you like Kenya shows?

GITHINJI: Any. The only thing is, if it’s interesting, I do watch.

COWEN: What would make a show interesting for you? What should the topic be?

GITHINJI: If it’s mostly talking about how I — our way of living, that is. I do like it very much because I do like getting more experience on how to stay with people.

COWEN: Your children, they live in Kenya? Yes.

GITHINJI: Yes, they live in Kenya.

COWEN: How many do you have?

GITHINJI: Me, I have two.

COWEN: Great. What do they do?

GITHINJI: One is married. Both of them are girls. One is married, the other one is in school.

COWEN: They live near here?

GITHINJI: Yes.

COWEN: That’s great.

GITHINJI: That one, I live with her at my place.

COWEN: What do you think is the next thing you will try to do for your community?

GITHINJI: Well, I would say I will just try to go ahead with giving them or showing them the way we should be living here. Living in a peaceful way.

COWEN: If you compare the views you have now to the views you had as a young person, what have you changed your mind about in life?

GITHINJI: I’ve changed my mind because now I know how to stay with people, good living.

COWEN: You understand other people better?

GITHINJI: Yes, more than.

COWEN: You see the importance of helping them cooperate.

GITHINJI: Yes.

COWEN: Do you have any questions for me?

GITHINJI: Yes, I can ask you one.

COWEN: Please.

GITHINJI: Do you stay here in Tatu City? Do you work in Tatu City, or you are just a visitor?

COWEN: I am just a visitor. I’m an old friend of Stephen Jennings, and I’ve never been to Kenya before. This is my first time. I wanted very much to come, and I knew Stephen here, so I thought I would see him, so I’m here for five to six days. My wife is coming, and then I go on safari with her. That’s my story here.

GITHINJI: That’s good. This Stephen Jennings is your good friend.

COWEN: He and I worked together over 30 years ago.

GITHINJI: Oh, that’s good.

COWEN: I had not seen him in a long time either, because he was in many distant places, and I live in America, near Washington, D.C.

GITHINJI: If at all he is your friend, just go and tell him to help our boys who are here, who are unemployed.

COWEN: How do you think he should do that?

GITHINJI: Well, as a community, he can look for a way, if you have employment here, you can just let us know, and we ship these boys of ours here. You can also help us with educating some of these young boys who need help.

COWEN: What do you think the rest of the world should know about Kenya, that they don’t know?

GITHINJI: Well, the only thing in Kenya — the only problem we do have in Kenya is only employment.

COWEN: You want to see more foreign businesses come to create more jobs?

GITHINJI: Yes.

COWEN: More Chinese investments.

GITHINJI: Yes.

COWEN: More Americans who work at Tatu City.

GITHINJI: If you could have more jobs, and you have more investors to come here and invest in us, when they’re coming to invest, we also benefit from the creation of jobs and whatever, because we have a lot of young people who are more educated, but they don’t have a living because they don’t have jobs here.

COWEN: Last question. Are you optimistic about Kenya, and if so, why? Are you optimistic about Kenya? You think the future will be better?

GITHINJI: Yes.

COWEN: Why?

GITHINJI: Because according to what I believe, as we are learning, we are learning how to shape our country in the best way possible. Whether in hard times or good times, we have to face all the challenges, and we have to make our country better. We have also to invite your friends to come and help us also, in one way or another, because east or west, home is the best.

COWEN: Githae Githinji, thank you very much.

GITHINJI: Thank you, also.