Elisa New believes anyone can have fun reading a poem. And that if you really want to have a blast, you shouldn’t limit poetry to silent, solitary reading — why not sing, recite, or perform it as has been the case for most of its history?

The Harvard English professor and host of Poetry in America recently sat down with Tyler to discuss poets, poems, and more, including Walt Whitman’s city walks, Emily Dickinson’s visual art, T.S. Eliot’s privilege, Robert Frost’s radicalism, Willa Cather’s wisdom, poetry’s new platforms, the elasticity of English, the payoffs of Puritanism, and what it was like reading poetry with Shaquille O’Neal.

Watch the full conversation

Recorded May 8th, 2018

Read the full transcript

TYLER COWEN: I am here today with Elisa New, up in Brookline. She is a professor of poetry at Harvard University and now producer, director, host, and star of the new PBS series Poetry in America.

Elisa, very nice to be with you.

ELISA NEW: Great to be here, Tyler. Thanks so much.

COWEN: To get into poetry, let me start with the question of what it is you all argue or disagree about. Let’s start with different interpretations of Emily Dickinson. I’m going to give you a few people who’ve written about Emily Dickinson, and you help us see what is contested in the world of Emily Dickinson scholarship, and what’s really at stake.

Take Martha Nell Smith. How would you describe her approach to Dickinson? What does she bring out?

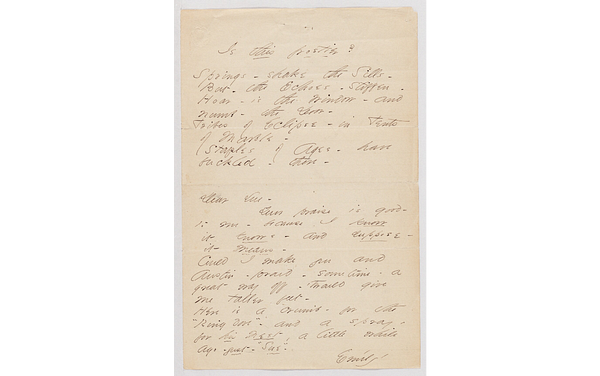

NEW: I had no idea you would be examining me, but I will do my best. Martha Nell Smith is one of those critics who reminds us that it’s really important to pay attention to the fact that Dickinson never actually published, except in the eccentric manuscripts we call “fascicles,” manuscripts that are collected at Harvard University and at Amherst University.

Martha Nell Smith is one of those critics who says that we should think of these manuscripts as visual texts, as almost texts in the visual arts.

COWEN: Like a calligrapher?

NEW: Yes, that the calligraphy matters, and that Dickinson was using the page almost as a dancer would create choreography.

So those who believe that we can actually understand Dickinson by reading the standardized punctuation marks that other editors have affixed to these beautiful and original texts, those other scholars sometimes come in for scouring and scorching criticism by the Martha Nell Smiths of the world. [laughs]

Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA

COWEN: When I look at an Emily Dickinson poem and I see all those dashes, what do the dashes mean — because other poets typically don’t use them — in your view?

NEW: They evolve for me. Sometimes they give the poetry an appropriately spasmodic gait [laughs]. Sometimes they feel like stitches of pain or of effort. They remind us that the poem is being written, is being composed. Sometimes they remind me of the thread Dickinson used to stitch her little books together.

There are critics who note that some of them point up and some of them point down and that they seem as much accent marks or musical kinds of notation. I love them. [laughs] I actually am agnostic or lax about them. I like them short as R. W. Franklin makes her dashes. I like them long as Thomas Johnson does, and I like looking at them in the manuscripts.

COWEN: Let’s say now I read Camille Paglia, who’s been a guest in the series. She’ll tell me Dickinson is all about homoeroticism, sadomasochistic surrealism, and brains being split open. Is that correct, and where does she differ from your view?

NEW: [laughs] I like that, too! Brains being split open, for sure — that Dickinson is a poet of trauma.

When I say “trauma,” she’s a poet who will say that the sound of the robins or the look of the daffodils mangles her, that [laughs] she’s sometimes without boundaries, without filters, without protections, and she tunes up sensory experience so, so high that “I felt a Funeral in my Brain,” she says.

There are a whole bunch of brain poems that take us to that place where we see an image that’s unbearable. We feel a headache that is tearing us open. We have a thought that suddenly crashes into other thoughts.

Homoeroticism, maybe. I am of those who think Emily Dickinson was a lifelong virgin who lived in her head. Much of the erotic life is in our heads, no matter who we touch. Fair enough, but getting too literal about it with Dickinson seems to me to subtract somehow.

COWEN: Your colleague Helen Vendler, what would she stress in Dickinson?

NEW: The exquisite craft of the individual poems. The extraordinary metaphors that just pay off and pay off and pay off.

Like, “There’s a certain Slant of light / Winter Afternoons — / That oppresses, like the Heft / Of Cathedral Tunes — ”

What kind of light is it that feels like music and that has weight? That is a feat of metaphoric derring-do of a kind that one finds in every line of Emily Dickinson’s.

In the poem I’ve just been quoting, she says that this light, “Heavenly Hurt, it gives us — / We can find no scar, / But internal difference — / Where the Meanings are — ”

What is it that justifies comparing light to sound, to weight is that somehow that synesthetic expression is more adequate to how great language feels in that place, wherever that is, “Where the Meanings are.” Helen is the most careful — and, thank heavens, the longest-lasting — New Critic who reminds us of all we gain by reading word by word.

COWEN: In your own work, you’ve stressed seeing Dickinson as a kind of skeptical Kierkegaardian, decentering everything. What is it that you’ve brought to this debate that you would stress now?

NEW: Well, that was a long time ago when I called her a skeptical Kierkegaardian. I think I did, and maybe I still would because everything’s at stake. Everything’s at risk in every second.

The poem is an experience that has never happened before in quite this way, and there is a leap, as Kierkegaard would have said, that every single Dickinson poem somehow constitutes.

You asked me, Tyler, in the very beginning about those dashes that seem also to act as the little frames or brackets. They say, “This word, and no other.”

There is, we might even say, an existential quality to these poems. But what I said, what one says about a poet as great as Dickinson 30 years ago, and what I would say today is somewhat different.

COWEN: If we read Walt Whitman, his language is greatly different from that of Emily Dickinson, and the feel of his work is much more democratic. How is it that the overall political, economic, theological feel of Whitman connects with the way he uses language? What’s the innovation in Whitman in that regard?

NEW: Well, Whitman was a walker in the city. Whitman came of age in Brooklyn at a moment when the modern urban metropolis that we can still see in the New York cityscape today in all of those 19th century buildings that are still there — when that was happening.

Whitman’s consciousness is educated by the vast architectural sprawl of his city, and then by all of the people who came flooding into this city, including not only northern Europeans from England and from the Netherlands, as Whitman’s family did, but runaway slaves from the South, and the Irish fleeing famine.

The whole stately procession and unstately bedraggled procession that begins to parade up and down Broadway with Barnum and Bailey’s — there was no Bailey — with P.T. Barnum’s circus opening in the Crystal Palace and the site of what would become Central Park. How could you not have a democratic consciousness when so much diversity is just springing up around you at every second?

That for me is the most powerful part of Whitman. There’s nothing that isn’t powerful because I so adore him. I think of Whitman as my rabbi.

[laughter]

But he was there at the beginning of American cities, and he has this fresh and original understanding of how a city wants to be a locus of democracy.

On the best poets

COWEN: Let me express a concern, and see if you can talk me out of it. I’m going to use the word best, which I know many literary critics do not like, but I believe in the concept nonetheless.

In my view, the two best American poets are Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman, and they were both a long, long time ago. They were quite early in the literary history of this nation.

Is that a statement about the fame-generating process, a statement about somehow their era was better at generating the best poets because we had a much smaller population, or am I simply wrong in thinking they’re the best American poets?

NEW: I don’t know what to say to you. I revere them. They are the most important poets for me. They invent two ways of being a poet, and two of the ways that so many poets who have followed them also acknowledge.

Would there be Hart Crane, Allen Ginsberg, Carl Sandburg, C. D. Wright, C. K. Williams? Would there be any of those — Frank O’Hara — without Walt Whitman? And they would be the first to say, “No.”

Would there be Susan Howe, Marianne Moore, Elizabeth Bishop, Sylvia Plath? All in different ways, would we have them without Emily Dickinson? I don’t know. I’m not sure I can enter . . . Is it that we’ve lost it? I don’t think that’s it. I don’t think we’ve lost it.

COWEN: I turn to European history, again using the “best” word, but it’s plausible to think Homer and Dante are the two best European poets ever in some regards, and they, too, are each quite early in a particular stage of history. What is it about poetry that seems to generate so many people as at least plausible bests who come at the very beginnings of eras?

NEW: Well, isn’t it that poetry is cumulative, and canons are cumulative, and those who are there first, they’re never superseded — unlike, say, for economists who would say, “Adam Smith is a really smart guy, but it’s not like we go to Adam Smith to understand Bitcoin.” They would say, “No. That knowledge has been superseded.”

In literary knowledge, we continue to learn from our predecessors and also continue to feel awe before the persistence of certain phenomena that they . . . Shakespeare saw that Iago was a slippery-mouthed conniver of a kind we still recognize.

We recognize ourselves. We recognize something enduringly human in these oldest of poets, and then, maybe, we elevate them even more.

On the elasticity of American English

COWEN: Is it possible that American English isn’t rich enough? I find if I go to Ireland, or especially to Trinidad, I envy the language they have there. They’re both speaking English. If you think of America today, there’s texting, now a long history of television.

Our language is great for quick communication, number one in the world for science. Now there’s social media. Nineteenth-century American English has longer sentences. It’s arguably more like British English. Isn’t the problem just the language we grow up with around us isn’t somehow good enough to sustain first-rate poets?

NEW: It is. It’s so rich. I love the way it evolves, the way my kids don’t say “whatever” anymore. “Whatever” had such incredible potency. “Epic.” When they started to say “epic” had such potency. When hip-hop artists say, “That’s really ill.”

I love the fertility of slang. I love the way mass culture, and its technological limitations, and then its new breaths does funny things to language. I tell my students about this. I say, “You know the way how in ’30s movies, the women are always sweeping around going, ‘Oh, darling,’ in The Thin Man, and there’s this ‘Hi, honey . . .’” [laughs]

If you watch a ’30s movie, and then you watch a ’50s movie, and you see the plasticity and the ingenuity that human beings put into . . . We don’t say, “Hey, kid.” We don’t call anyone a kid anymore. It sounds really archaic and corny.

COWEN: Unless it’s a kid.

NEW: Well, we might say “kid.” But for me, it’s not “Is it better or worse?” but “Is it moving? Is the language refreshing itself?” John Ashbery, whom we lost recently — it could be that John Ashbery 100 years from now is going to seem crystal clear to those generations.

COWEN: I don’t think so.

NEW: Well, he might seem crystal clear because we will be accustomed to thinking in the cut-up way, in the media-fied way that he saw earlier than the rest of us. Who knows? I don’t get a lot by making lists, myself, of the best. I have a craving for the new and the fresh as well as for the old . . . I guess I said some of this before.

What we love about the greatest poets is that, as Emerson says, they echo back our own thoughts with “alienated majesty.” It’s the most familiar things they say that we are moved by the most.

COWEN: Which is more interesting, Instagram poetry or Facebook poetry?

NEW: I’m not going to be a good judge of that. Like many people, I have to figure out what filters I need in order to survive in the world, and I am not a social media devotee. But I am all for pushing poetry, trying poetry on all of these different platforms and in all forms of media.

COWEN: Rupi Kaur from Canada — she has two million Instagram followers. A year ago, her book was number two for the whole year. She sold more copies than Hillary Clinton did. She was 77 weeks on the New York Times Best Sellers lists.

She probably is not in many poetry anthologies. Most of her poems are a few lines long. What are we supposed to think of this? Is she the world’s leading poet right now, rap music aside?

NEW: Again, I’m not an economist — although married to one. I wouldn’t trust the moment’s market on poetry. I would say this about many things: we are in the middle of an interesting kind of generational shift, where a younger generation that’s grown up on Facebook and on a lot of sharing and a lot of sociality wants to hear about the personal lives of their peers. [laughs]

And I haven’t figured it out. It doesn’t seem to me that I have the right tools. I feel too old.

COWEN: Do you worry about the dominant economic role of the poetry anthology for generating royalties? If you’re a poet, as you know, it’s hard to sell a lot of book copies if you’re not, say, on Instagram with a lot of followers.

You get a poem in one of the anthologies. That’s a fairly centralized market. Do we have a funny market structure for poetry, where there’s one part, far too centralized, run by anthologies, driven by classroom use — and then another part that’s a kind of Malthusian equilibrium. Everyone writing poetry on the internet. Hardly anyone earning anything.

And then you have a few poets, driven by their celebrity status, who earn a lot of money. But it’s a feast-or-famine situation. There’s not a healthy middle of the market.

NEW: In the arts, has there ever been a healthy middle of the market? Arts are not restaurants, right? [laughs] Restaurants — there’s the top, there’s the bottom, and there’s the middle.

Artists have always depended on either patronage or somebody driven for love of something other than the art itself to get themselves distributed. I don’t think one becomes a poet in order to earn a living.

I’m not sure there’s any poet — including Billy Collins, whom I like very much, and whose work I admire very much — who can earn a living writing poetry. Happily for our culture, what many of the great poets in the culture do is they teach, which I think is a really important role for creative people.

I’m not sure there’s any poet…who can earn a living writing poetry. Happily for our culture, what many of the great poets in the culture do is they teach, which I think is a really important role for creative people.

COWEN: Wallace Stevens worked for an insurance company.

NEW: Yeah, he did.

COWEN: William Carlos Williams was a doctor. Dana Gioia was in the food business. Are too many poets today in the academy?

NEW: Are too many poets in the . . .

COWEN: Too removed from the worries of everyday life, too tenured. Do you agree or not? Should they be out on whaling ships?

NEW: I think I should be. I think I can speak for myself here. I have stepped out of the academy by finding a way, a format, a distribution channel, and accepting the limitations of 24 minutes in order to speak to doctors, lawyers, postal workers, delivery people.

I have said, “We who have lived in the academy ought to get out a bit.” [laughs] I can say for myself, I’m very happy to have gotten out in the world. What I have learned is that one doesn’t need very special equipment or even a lot of technical knowledge to read a poem, even a difficult poem, with deep understanding.

COWEN: What do you think of the notion of poets who do harm? T. S. Eliot, for instance — he claimed Milton, whom he thought was a great poet, but did more harm to 18th century poetry than either Dryden or Pope. Are there poets today — great though they may be — who are in a sense doing harm to poetry? And how should we think about that?

NEW: Are there poets doing harm to poetry? I think T. S. Eliot was too fastidious about such matters. Poetry survived John Milton just fine. I would rather ask the question, [laughs] “Ask not what poetry can do for you, ask what you can do for poetry.” Or ask what poetry can do for the world. Ask why we need poetry.

William Carlos Williams, who did not like T. S. Eliot, reminded us that — what did he say? People die every day for want of what? Poetry, what poetry can offer, by which he meant a way of thinking about the wrenching complexities and compromises that we all make every day.

COWEN: Was Samuel Johnson right that no person ever wished Milton’s “Paradise Lost” to be longer than it was?

NEW: [laughs] I did not wish it longer myself. Poe said that no poem should be longer than 108 lines; 108 lines, Poe calculated, was exactly the maximum amount that you could read in one sitting. He thought that poetry should have that kind of experiential, explosive pow effect, and that anything longer than 108 lines couldn’t have that.

But by that criterion we wouldn’t have Dante’s . . .

COWEN: Or Walt Whitman.

NEW: Or Walt Whitman, although I would never recommend reading “Song of Myself” in one sitting at all. I think a poem like “Song of Myself,” these 52 parts, is a poem for a lifetime, and many, many occasions of casual browsing on the grass, and not a poem that you just grind through.

COWEN: We’ll get back to poetry, but let’s try a few questions about America, and as always, feel free to pass anything you don’t want to cover.

We’re up here in New England. It’s wonderful. It’s a beautiful day. If New England is so wonderful, why is it depopulating?

NEW: I didn’t know that.

COWEN: It is.

NEW: It’s expensive to live here, but I actually have no idea. What you make me think of is the 1890s, when New England was depopulating because the mills were shutting down, and the textile industry was moving out of New England. What’s happening now?

COWEN: People are moving to the South, basically.

NEW: We’re getting older.

COWEN: There seems to be a strong preference for sun for all age groups, and this, to me, is surprising.

NEW: I like it here.

[laughter]

COWEN: Why would anyone ever have wanted to be a Puritan?

NEW: That’s a great question. That’s a terrific question and one that I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about. Being a Puritan is a great way to live a psychologically very candid life, [laughs] if what you want is actually not to be repressed at all.

We think of the Puritans as very repressed, but instead, you want to be marinating in and giving a lot of attention to all of your own insecurities and sense of, “I goofed that up. I messed that one up. Oh, that didn’t work out very well.” If you want to cultivate your inner life, it’s really great to be a Puritan.

We think of the Puritans as very repressed, but instead, you want to be marinating in and giving a lot of attention to all of your own insecurities and sense of, “I goofed that up. I messed that one up. Oh, that didn’t work out very well.” If you want to cultivate your inner life, it’s really great to be a Puritan.

If you want to live a kind of high-octane life of extremes, you want to feel the exultation of a day like this in New England, where the green of the grass and the blue of the sky announce to you that God’s creation is the most eloquent of all creations. If that’s what you’re after, that kind of intensity, New England Puritanism is a really good religion for you.

I’ve just been paraphrasing Jonathan Edwards, who, even though he was the writer who said that we were spiders hung over the fire who would sizzle on a . . . I think it’s Robert Lowell who said that we would sizzle on a brick. He said we’re spiders hung over the fire — also wrote these gorgeous lyrical essays on the natural world that drew from aesthetic experience, increased piety.

If you like intensity rather than moderation or serenity, if you like intensity, a Puritan’s a good thing to be.

On whether American art is overrated

COWEN: If we think about America, it’s the world’s wealthiest nation, most powerful nation. It has a disproportionate share of the top universities, including, of course, Harvard. Is this going to mean that, in essence, most things American are overrated?

More people read English, so if you’re an American author or American poet, people will study you. They will write about you, and compared to, say, Neruda and Mistral from Chile, or writers, poets from other parts of the world, American artists, maybe they’re all overrated, overpriced. Do you agree?

NEW: I don’t know. I’m having trouble with these valuation questions that American poets are overpriced . . .

COWEN: American movies, American artworks. There’s simply more money chasing after them and more attention because we’re America.

NEW: You would probably be better at answering that question than I am. When I turn on Netflix, I’m often curious about unfamiliar worlds. Think about the Nordic noir, the new emergence of these serial spy shows that take us into Oslo and Stockholm. They’re so fascinating.

But I don’t think that answers your question.

COWEN: A question related to your mentor, or one of your mentors, Ann Douglas. As you know, the mid- to late 19th century was, at the time, seen as an era of a kind of extreme feminization. I don’t think we today would view it in those terms, but they did.

Do you see any parallels between that time and the world today?

NEW: That’s a very interesting question. That was a curveball. Thinking back to my wonderful mentor’s work, The Feminization of American Culture, where Ann Douglas offered a critique of a sentimentalization of female experience that excluded, in her mind, and ended up marginalizing whole other orders of experience like that so brilliantly exposited by Herman Melville.

The literature of the period tended to exclude the experience of the outside world and to focus on the experiences most women had within the domestic realm.

Do I think that right now we are in a period of feminization? Once again, things are happening so fast that I don’t know. We’re certainly in one of those moments when we are reckoning, in all sorts of ways that contradict each other, with what it is to be men, women, or in-between.

COWEN: What’s a book you would recommend for people to read about America that would help them understand this country that’s maybe not so well known?

NEW: The book I would recommend is The Scarlet Letter, and it is well known, but not well read. I think The Scarlet Letter is as relevant today in the #MeToo era, and has been for decades informative and enlightening for me as I’ve watched a social hunger for the toppling of the mighty, right?

We love both to revere those who may not deserve our reverence and to pull down anyone who is available. So I would recommend that one.

To understand some of our diversity threats in a way that might cool us down a little bit, I would recommend Willa Cather. Willa Cather, who writes about the American Midwest, which we don’t think of. We think of the Midwest as where all the Americans are.

In My Antonia, which I taught a few weeks ago, she writes about the Midwest when it was being populated by Norwegians, Bohemians, who were Austro-Hungarians. When all of the people from middle and northern Europe were settling the Midwest, and there was ethnic pandemonium [laughs] right there in the middle.

That the struggles, that our disagreements and unease about difference have always been with us, are not regionally specific. There aren’t really red states and blue states. They’re just at this moment redder and bluer. I think we can all profit from reading Willa Cather.

COWEN: Let me toss out the names of a few poets, and tell us either why they’re important to you or what you would direct our attention toward or give us some kind of deeper insight . . .

NEW: I hope I get to say, “I don’t know.”

COWEN: Sure, but this one. Robert Frost.

NEW: I love Robert Frost. What I would direct your attention to is that he’s not a doddering old fart mumbling platitudes. He’s a radical.

He’s a radical poet who is teaching us again and again how much of our joy is mixed with pain, how much of our work and our joy in our work is charged with either integrated eroticism or repressed sexuality. He’s extraordinary at looking dispassionately at how hard it is to be in a lifelong partnership.

His husbands and wives are so often mismatched and maladapted one to another and the natural world. He’s a great inheritor of that Puritan tradition, even though he was born in California. He embraced a New England ethos, which tells us it’s good to acknowledge our pain.

COWEN: Switching to Topeka, Kansas, Gwendolyn Brooks.

NEW: What do I love? To say her homeliness would be the wrong word.

OK, so here’s the posture of a Gwendolyn Brooks speaker. She’s the woman looking out the window at the neighborhood and clucking her tongue or breathing a sigh of relief that things haven’t gotten worse.

There is a mature knowledge in Gwendolyn Brooks of how communities and the individuals within them muddle along, and that some people are bound to go to jail and other people will somehow take care of each other, eating beans, eking out what happiness they can.

Gwendolyn Brooks somehow makes us care about people in straitened social circumstances to whom different things — often things they don’t deserve — will happen.

COWEN: Here’s a much tougher one, I think: Ezra Pound.

NEW: I’m not an Ezra Pound fan. I, as a Jewish American, can’t really get past his anti-Semitism, and I’m not interested enough in the beautiful, musical effects that he produces by taking Provençal French and Homeric Greek and the American idiom and putting them together.

He is, for those who care about him, the technician par excellence who understands the native sounds of language and how to put them together. But I like my poets to give me some wisdom, and I don’t find him wise.

COWEN: In general, how should we think about poets from the past who held highly objectionable views? T. S. Eliot maybe was less anti-Semitic than Pound, but not really on safe ground, either. Picasso was a Communist, seems to have treated women very, very badly.

Is there a general approach? Is it case by case?

NEW: I am not in the business of striking people off of reading lists or of striking people off of lists at all. For whatever reason, great art is often fertilized by bad character.

Hemingway wasn’t a very nice guy either, but man, he really could write some killer sentences, and I learn from them. But I do think we get to all have taste, and some writers . . . T. S. Eliot, probably because of the years he spent in Cambridge, I don’t find him very wise either.

COWEN: Because of Cambridge?

NEW: Cambridge didn’t make him wise. It didn’t help him at all. T. S. Eliot was always a person of too much privilege and a person who made such bad choices. The combination of so much privilege and such bad choices gives us the magnificent accident of “The Waste Land,” which is magnificent.

COWEN: It bores me a bit. I loved it as a teenager, but when I try to read it again, I’m not that interested.

NEW: You know what I think, Tyler? I think we didn’t go through World War I so we can’t say. I do understand the T. S. Eliot that incubated in Cambridge in 1913 because Cambridge in 2018 isn’t that different. It’s really the same world.

I think “The Waste Land” is the poet of a pretty privileged American who went to Europe and was really hoping that European civilization would hold together, and instead it was blowing itself to smithereens.

When I read Eliot next to the American modernists whom I prefer — I prefer Marianne Moore, I prefer William Carlos Williams, I prefer Hart Crane, I prefer Edna St. Vincent Millay — I think, “Well, they didn’t really do World War I, either.”

COWEN: Now, Bob Dylan has won the Nobel Prize in literature, as you know. Do you consider him a poet?

NEW: Yes, I do.

COWEN: What’s his most poetic song?

NEW: I love “Buckets of Rain.” I don’t know if it’s his most poetic song.

COWEN: But it’s the one that comes to mind.

NEW: “Buckets of rain / Buckets of tears / Got all them buckets coming out of my ears.”

I have been reading recently in the work of Stephen Sondheim and learning from Sondheim how to think about lyrics and poetry, and I’m not at the end of that period of study.

I’ve felt for a long time that we made a mistake when we decided — and we decided this a hundred years ago or so — that poems were things we read on a page by ourselves silently, rather than poems were things we read around a fire to each other or recited after school in a pageant or sang with music and jesters.

I’ve felt for a long time that we made a mistake when we decided that poems were things we read on a page by ourselves silently, rather than poems were things we read around a fire to each other or recited after school in a pageant or sang with music and jesters.

“Walking Down the Street” from my friend Robert Pinsky will point out that for most of the history of poetry, there was music and jesters, too, so that poetic language should be part of the pageantry of a rock concert makes perfect sense to me.

COWEN: “Visions of Johanna” would be my Dylan nomination, by the way.

Sondheim, I think, reached a peak for integrating lyrics and rhythm in a way no earlier American popular composer had done.

NEW: He thinks about it so hard. It sounds like you’ve studied it more than I have, and you’re ahead of me there.

On poets as novelists, and vice versa

COWEN: People who are novelists and poets. Some — Thomas Hardy was great at both. Melville, it seems he fell short as a poet. Edith Wharton . . .

NEW: He’s a great poet. I think Melville’s a great poet.

COWEN: You mean “Battle Pieces” or . . .

NEW: I mean “Battle Pieces.” “Clarel” is a little bit like “Paradise Lost,” only not.

COWEN: More so, yes. Edith Wharton, probably not a great poet, right?

In one of your articles, you argued Ralph Waldo Emerson, precisely because he was successful as a philosopher, he had a kind of universalism to his thought, and that may have held him back from being great as a poet.

Why don’t we have more people who are both wonderful novelists and wonderful poets?

NEW: I think they really do — and this is a very banal way of saying it — they really do call on different skill sets. The sort of distillation and often asocial concentration that it takes to be a lyric poet is quite different from the crowded, cacophonous, socially alert set of faculties one needs to write a great novel.

I teach both. I teach poetry, and I teach the novel and was, in fact, talking yesterday with a graduate student about the differences. It doesn’t surprise me at all that people don’t move easily between those.

Thomas Hardy, I think, wrote his greatest poetry after his wife had died, and he was in some way delivered into lyric loneliness. I think lyric loneliness is helpful by that event.

Melville is a great poet in “Battle Pieces” because he lets all the deforming and torqueing energies of the war and of his psyche — he lets them fall as they may on the page, so he’s perhaps an example.

I’m going to be in Chicago tomorrow filming with some first graders who are going to be reading bird poems, haiku in particular, written by Richard Wright. Now Richard Wright, the writer of “Native Son” and “Black Boy,” is not a person we would expect to have authored a bunch of beautiful poems about sparrows, not a writer we might have expected to find haiku, but he did.

COWEN: Do you think we’ll learn anything from applying artificial intelligence and machine learning to poetry? Or do you view that as a dead end?

NEW: I do view it as a dead end. Certainly we will learn something, but it is our humanity that poetry most meaningfully serves. It’s our humanity. It’s our unique intelligence that our language holds.

I hope we will regather to us, that we will cherish more the things about us that are just human.

COWEN: As you may know, Emily Dickinson once wrote that she would read backwards the poems of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, maybe to de-familiarize herself with them in some way. Should we memorize poems, or does this take away their daring and surprise?

There are some Bob Dylan songs you don’t want to listen to too many times. Are poems the same?

NEW: I think it’s great to memorize poems, but not all poems. In the case of Emily Dickinson, there are almost 1,800 poems, and I don’t think I’m ever going to get to read them all attentively, much less memorize them all.

I like memorizing two to four lines of a poem and just walking around with that little fragment. I have talismanic poems like, “Nature’s first green is gold / Her hardest hue to hold.”

That’s just the first two lines of Robert Frost. But when the first leaves come out — here it was about 10 days ago — they are gold.

So I just say that. I salute the world with those words. To have them inside my head and ready for me to extend and salute is a deeply pleasurable thing.

I like memorizing two to four lines of a poem and just walking around with that little fragment. I have talismanic poems like, “Nature’s first green is gold / Her hardest hue to hold.” That’s just the first two lines of Robert Frost. But when the first leaves come out — here it was about 10 days ago — they are gold. So I just say that. I salute the world with those words. To have them inside my head and ready for me to extend and salute is a deeply pleasurable thing.

On starting with poetry

COWEN: Let’s say I’m a programmer. I work in Silicon Valley, and I’ve never really read poetry. I might’ve even dropped out of college, but I’m very smart.

How should I start in on learning something about poetry in a way that will perhaps work for me? What’s your advice?

NEW: Buy one of those anthologies. Buy any poetry anthology, and don’t try to start at the beginning and work your way through. Just open it up and see if something grabs you. If something grabs you, read it once and read it again.

Another technique I often recommend is, if there’s a poem that you think will interest you, print it, just it, just this one poem. Print, it’s an old technology, but do it. It’s better than reading it on your phone. And put it in your pocket.

Put it in your back pocket, and pull it out while you’re standing in line somewhere or waiting for a bus. Pull it out and just let your eye bounce around it. I think that letting a poem nudge and nuzzle up against your life [laughs] and to treat it . . .

Whitman recommended this. He felt we should treat poems casually. He said, “Loafe with me on the grass.” [laughs] That was the posture he recommended for reading poetry. “Loafe with me on the grass.” Relax into this language of another person. I think that being casual about it . . . and you can always watch a pretty good TV show on public television if you want some inspiration.

COWEN: Poetry in America, yes, which you can buy on Amazon, by the way.

Let’s say you’re a parent. You love poetry. You have children. They don’t know much poetry yet. You understand coercion is often counterproductive. How do you seduce them into poetry?

NEW: You just read to them when they’re little.

COWEN: Just don’t stop.

NEW: You just read to them until they tell you to stop. You read through. With two of my children, I got all the way through Little Women. I read all of Little Women to a fifth or sixth grader, who could certainly read herself.

She could have read Little Women, but that I was reading it to her, chapter after chapter, and reading her Emily Dickinson. Sometimes if we see one of those leaves, I might say, “Nature’s first green is gold / Her hardest hue to hold.”

I think children, whether they acknowledge it or not, when they’re young, they really do pay attention to what we do and what we care about. If we read, they read. If we read to them, they’ll read to their children.

Kids love poetry. They love poetry they can’t understand. They don’t only like rhyming poetry, although they like that. They like the puzzle in it. Here’s two lines of Dickinson’s I love. “We like March, his shoes are purple.” [laughs] “We like March, his shoes are purple.”

What does that mean? “His shoes are purple.” I guess it refers to the first crocuses or to the soaking of the ground. You ask a second grader, “Why are March’s shoes purple?” and they like to talk about it.

COWEN: Do you have a Shaquille O’Neal story or impression that you’re able to share with us?

NEWWhat a hoot it was, [laughs] reading poetry with Shaquille O’Neal. I think the funniest thing for me was that they had to put me on this chair. They had to take this stool, I guess they’re accustomed to doing this, so that I didn’t look like a teeny, weeny, weeny, little person. He was sitting in a normal chair. My feet when I interviewed him were hanging way, way above the ground. He was splayed on the ground.

He’s immensely thoughtful. He’s quick-witted but deep. He was really ready to read a poem with me. He was all over it. He was all over it, and I loved his gusto. We were reading a poem that rewarded quick wits, but actually also rewarded the capacity to pause and say, “Hmm.”

In the course of our conversation, he realized this was one of those poems where he was going to have to say, “Hmm.” I love that he slowed down.

COWEN: I’ll close with two questions very directly about you. To invoke the economist’s concept of comparative advantage — and please be immodest — how would you describe or characterize what you bring to poetry that maybe other people don’t quite as well?

NEW: I think I bring a belief in the capacity of any person sitting across from me to have a blast reading a poem. I really believe that human language — even encoded in some of the arcane ways, poems, and code — language is fascinating to other human beings.

Somehow, I persuade others to believe with me that they can have a blast reading a poem, and that the development of understanding that can occur as you read 15 lines or 20 lines is just about as much fun as you can have, and a cerebral kind of fun, the sort of fun that some people look to in the Sunday crossword puzzle or the Wednesday cross.

It’s that kind of fun, and I think that visiting with me, if you’ve never tasted that kind of fun, it might be worth trying.

COWEN: Last question. You meet an 18-year-old, and this person wants in some way to be a future version of you, Elisa New, and asks you for advice. What advice do you give them?

NEW: Teach.

COWEN: Teach.

NEW: Yes, teach the young, and yes, that’s the advice. Because what teaching is, is learning to converse with others. It’s to experience a topic as it grows richer and richer under the attentions of a community. That’s what a classroom that really works is. It’s a community that’s ever rewarding.

COWEN: Great final answer. Thank you, Elisa New, and again, for our listeners, her PBS show is Poetry in America. On TV of course, but also available for purchase on iTunes, Amazon, and other places. Thank you for the conversation.

NEW: Thank you so much, Tyler.