For two hours every morning, David Brooks crawls around his living room floor, organizing piles of research. Then, the piles become paragraphs, the paragraphs become columns or chapters, and the process — which he calls “writing” — is complete.

After that he might go out and see some people. A lunch, say, with his friend Tyler. And the two will discuss the things they’re thinking, writing, and learning about. And David will feel rejuvenated, for he is a social animal (as are we all).

Then one day David will be asked by Tyler to come on his show, and perform this act publicly. To talk about his love for Bruce Springsteen, being a modern-day Whig, his “religious bisexuality,” covenants vs. contracts, today’s answer to the “Fallows Question,” why failure is overrated, community and loneliness, the upside of being invaded by Canada, and much more.

And though he will be intimidated, David will oblige, and the result is here for you to enjoy.

Watch the full conversation

Recorded May 14th, 2018

Read the full transcript

TYLER COWEN: Hello, everyone. Thank you for coming, David. David is actually part of the genesis of this series, though he doesn’t know it. Periodically David and I get together for lunch and just talk about different things. And it occurred to me that there ought to be some product version of this that would be free and open for everyone. So here we are, and finally it’s David himself in the flesh for me to talk to him.

So I’d like to start with what I call the “Eleanor Rigby” question. “All the lonely people, where do they all come from?”

[laughter]

What’s the root cause behind the loneliness epidemic? Why can’t we just bring these people together, use the internet if need be, and make them all un-lonely? What’s the actual underlying problem?

DAVID BROOKS: Okay. First let me say, I would come back from our lunches, and my assistant would say, “You’re glowing, you have such a man crush.” So here we are. I’m glad we can do this in public.

[laughter]

This is the most intimidating interview I’ve ever sat down for because (a) you know me, and (b) you actually read my stuff. Two things that are rare.

[laughter]

I’m a cultural determinist. So I tend to think the loneliness is primarily a cultural problem, that we went through a culture in the ’50s where we were the opposite of lonely. We were in a culture where people had to solve big problems because they had a very group-oriented culture, what you might call the “We’re all in this together.” Big unions. Very tight neighborhoods. Conformist organizations. Deference to authority.

And then people decided around about 1962 that wasn’t working. And so they created a culture that was very individualistic. If you go back to the “Port Huron Statement,” if you go to Betty Friedan’s Feminine Mystique, people begin to value autonomy. We need some lack . . . It’s too soul crushing, this conformity.

So in my view, we’ve had 40 or 50 years or more of individualism. And there’s been individualism of the left, which has been about social individualism and autonomy. There’s been a right-wing version, which is more economic autonomy. But it’s been autonomy all the way down.

In my view, if you leave people naked and alone, they do what their evolutionary roots tell them to do, which is revert to tribe. And so they pick a bad form of community, which is tribalism. But my explanation would be primarily cultural because there’s no reason people should do what’s bad for them, which is to be alone. But that’s what’s happened.

COWEN: Let’s say we consider this from the point of view of women. So in the 1950s women had much less autonomy. Could it be that an ideology of individualism was what we needed to partially liberate women?

Some men are left lonelier because women are in fact independent. And the other side of the coin is independence of women. If you think of women as often a kind of glue holding communities together, so we’ve traded off community for liberation of many women. And maybe (a) there’s no going back, and (b) it’s actually a good thing — or no?

BROOKS: I would put it halfway like that. I forget who said this, but there is a social theorist who has a theory that culture moves forward by what she calls the “ratchet, hatchet, pivot, ratchet” phrase. Culture is our collective response to solve a problem. And so you solve a problem and society ratchets upwards. It works for a little while, and then it stops working. So you have a hatchet phase, where everybody chops up the culture.

I would say the 1960s were a period of chopping up the old culture. Then you shift over because humans are very ingenious. And you ratchet upwards. But then it stops.

So I’d say, my explanation was, we had to get rid of that 1950s culture because it really — it tolerated a lot of racism, a lot of sexism, a lot of anti-Semitism. People were emotionally cold with one another. The food was really boring.

[laughter]

So we had to chop that up. Then we had to move over to an individualistic culture. We couldn’t have had feminism and civil rights of women. I doubt we could have had Silicon Valley without that rebel, individualistic, autonomy ethos. But every truth becomes false when you take it to its extreme. And so I’ve said, we’ve sort of run out the string on that one.

I would say that one of the things that’s noticeable about affluent people — and this has happened to me — is, as soon as people make money, they seem to purchase loneliness. I grew up in the city, super crowded. When I had a book sitting over there, I had a best seller, which allowed me to buy a house. And I bought it out in Bethesda with a big yard because I thought that was cool. I remember the moment I put the garage door thing on the visor of my car. That was one of the biggest moments of my life.

[laughter]

I would say that one of the things that’s noticeable about affluent people — and this has happened to me — is, as soon as people make money, they seem to purchase loneliness.

BROOKS: I had made it to suburbia. But then you realize, “I got a big acre yard, and I’m lonely.” And I think that’s a common phenomenon, that people take money and translate it into loneliness.

COWEN: There’s one study of the Amish — it only has 52 data points, but it seems to show they’re not especially happy. They’re a little bit above the neutral level. And they have strong community. If you ask them, “Are you happy with their community ties?” you get very high numbers. If you ask them, “Are you happy with your own life?” you get pretty low numbers. And there’s no great demand to in-migrate to the Amish. A few people have tried, but . . .

[laughter]

Why isn’t it that demonstrated preference is what we should take seriously when it comes to assessing how much individualism we have? Because you can join groups relatively easily still, right?

BROOKS: Yeah, well I would say if you ask people, “Are you lonely?” it used to be 20 percent who said yes, and now it’s 40 percent. If you look at suicide rates, suicide rates are now at a 30-year high, and suicide’s a proxy for loneliness. Fifty thousand people die every year of opiate addiction. There’s a massive upshift in social distrust. So to me, the idea . . .

Steven Pinker wrote this book on how we’re all doing better. His data was primarily about individuals. If you try to collect data on the quality of relationships, it’s really hard to find data that’s anything but bad. And so people, societies fall into patterns that are pretty self-destructive. And I’d say we’ve fallen into the pattern. I think we’re going to fix it.

But one thing about the Amish, I do think you have to control for their Germanic temperament.

[laughter]

BROOKS: But aside, I think the beauty of America, which separates us from other countries, frankly, which have much more inherited community . . . we form community, and then we live in it for a little while. Then somebody offers us five bucks an hour to move somewhere else, so we go somewhere else. So to me it’s the act of not inheriting community but forming it, and then leaving it, and then forming it again that creates the creativity of this culture.

My favorite Westerns are almost all John Ford Westerns. The greatest movie of all the time was The Searchers, by the way, starring John Wayne.

But there’s another movie, made with Henry Fonda, called My Darling Clementine, which was the most accurate Western because it’s about people forming a community in the West. It wasn’t a single guy having a gun shoot-out. The teacher comes to town. The Shakespearean actor comes to town. They put up a schoolhouse. It’s a movie about community building. And that’s actually how the West was founded.

COWEN: So you just spent two weeks in Italy, you told me. If we think about Italy, family size is quite small. Total fertility is at about 1.3. People are marrying at much later ages. That’s making them much more alone. You could say they’re becoming individualistic whether they like it or not. Does that strike you as a problem?

Japan would be another example, some parts of northern Europe. People are marrying late. Low birth rates. So almost by definition, they’re cut off from community of family compared to how things were 30, 40 years ago. But they seem to systematically make these choices, be happy with them. Would Italian women be better off with three kids in an apartment in Rome?

[laughter]

BROOKS: You want me to tell Italian women how to live?

[laughter]

I will say, I just got back. This is where you separate your own lived experience from the data because my ideology, my prior is that a low fertility, they should definitely fix that problem. But I was just out in Tuscany on a restaurant over a hillside, and we were surrounded by Italian families. And we were probably three-and-a-half hours into the meal before they served the entree.

[laughter]

I guess it was just expected you would sit there five or six hours because it’s Sunday afternoon. What are you going to do? But I don’t know. I can’t speak for Italian families. And I wouldn’t want to translate anything into happiness.

I’m in arguments with people who do happiness research. I find the whole field doesn’t live up to — if you look at novelistic or musical expressions of happiness — Tolstoy wrote a story called Family Happiness. “Ode to Joy.” The literary and musical capturing of what joy feels like is so much richer and more nuanced than anything in the happiness data, that I find the happiness data very unsatisfying.

All the happiness researchers say, “No, no, it’s really thick.” But to me, this is a failure, just a failure of social science. Anything you can reduce to data that’s as humanistic as joy and happiness . . . it seems to me there are so many different kinds of joy and happiness that are not captured in the data.

I now have taken to clipping out. When I see a description of joy, I clip it out. They often involve rhythmic movement with groups of people marching or dancing. But they’re often a sense of what was formerly inside yourself merging with something outside yourself, and a sense that people get caught up in the sense of spiritual transcendence, whether you’re marching across a bridge in Selma or Emerson being the universal eye when he was out in the forest. It’s always the loss of sense of where the self ends that seems to produce joy.

COWEN: You sometimes describe yourself as a conservative, as I would do for myself. But I think we would all recognize there’s some level of stagnation in a society, where at that point you have to take chances, or you have to make radical changes. And conservatism in the literal sense becomes virtually impossible. Do you think we’re at that state right now? Or if we’re not, how will we know when we get there?

BROOKS: Well, I’m an American conservative. My two heroes are Edmund Burke — and Edmund Burke’s core conservative ethos is epistemological modesty, the belief that the world is really complicated, and therefore the change should be constant but incremental.

COWEN: But America’s not built on that.

BROOKS: Right, so that’s one half, but then my other hero is Alexander Hamilton, who’s a Latino hip hop star from the heights.

[laughter]

His conservatism was very different. It’s about dynamism, energy, transformational change. And so a European self-conservatism doesn’t work here. You have to have that dynamic, recreated, self-transformational element. And I would say we’re definitely at a moment of . . . Certainly it’s impossible to argue we’re not at a need of some sort of political transformation because we’re completely dysfunctional.

COWEN: So there’s some big bet we ought to be making, doubling down on something. Do you have a sense, for you, what that would be?

BROOKS: Yeah, my short answer is that I’m a Whig. I believe in the Whig Party. The Whig Party was started by Hamilton, Henry Clay, Daniel Webster. And the basic argument of the Whig Party is that there are always conservatives or libertarians who believe in limiting government to enhance freedom, and progressives who believe in expanding government to increase equality and social economic security.

But Whigs believe in limited but energetic government to enhance social mobility. They had national banks. They had infrastructure plans. They believed in credit markets, and it was all an effort to create dynamic economies where poor boys and girls could rise and succeed. And so I would like to see a rediscovery of the Whig Party. Now, there are six Whigs in America right now.

[laughter]

BROOKS: But I’m one of them. So I’m sticking with it.

COWEN: Do you think conservatives ever really can win on social issues anymore? Or has that train simply left the station? Social liberalism has triumphed forever. One can stand up and yell “Stop,” but basically there’s no returning? Or do you think it’s fluctuation back and forth?

BROOKS: Well, I’d say on some things that train has probably left the station. On gay marriage. I don’t think in my lifetime, in our lifetime, we’ll see any reversal on gay marriage. On abortion, the data is pretty . . . If anything, there’s a bit of a movement, especially among the young, toward a more pro-life position.

And on the basic stability of bourgeois virtues, I think the conservatives are actually winning that argument. My friend Charles Murray put it that a lot of people on the left think left, but they definitely live right. And so the acceptance of bourgeois virtues, of stable families and pretty narrow, self-disciplined lifestyles — that seems to me almost without argument these days.

On religion and secularization

COWEN: And do you accept the secularization thesis, that the West will become less and less religious and will never go back? Or is that also cyclical with mean reversion?

BROOKS: I think that’s always wrong. The secularization . . . Peter Berger, who died, I think, at age 197 last year — I think he disproved that in the 1970s. The idea that America is going more secular — or as you get richer, you get more secular — I think it’s demonstrably false.

And even though we’re seeing religious polarization now, there’s a lot of people getting much more religious. If you walk through northern Central Park on a Saturday afternoon, you just see hundreds of Modern Orthodox kids who are trying to meet each other in the park there. That’s sort of their meat market on the Great Lawn. So in Judaism, the Orthodox are surging.

Then among Christians, they’re losing a lot of members because evangelicalism has disgraced itself with Trump. But on the other hand, if you go to New York, to the hip areas of New York, and you hang around 20-somethings, they’re going to churches. There’s a church called Redeemer, which has a bunch of plants around New York. There’s one called Trinity Grace. There’s one called C3. You go into these churches, and it feels like you’re going into the hippest nightclub on Earth, and they’re surging with enthusiasm.

I don’t know what the data show, but just my observation of both these different communities — orthodoxy in Christian and Jewish circles — is that, especially among the vanguard, the cultural vanguard, there’s a spiritual resurgence.

I teach at Yale, and 15 years ago, if you were religious it was like having acne. It was sort of uncool. Then it went neutral, and now it’s sort of a plus. It’s seen of a sign of your, some spiritual depth, even among those who are pretty secular themselves.

COWEN: But if you think of Sweden, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Italy, Japan, many nations — they seem to be rather drastically secular, even if people, in some fairly neutral sense, still believe in God.

So do you think we’re the last holdout, in a sense, amongst wealthy nations? Or do you think we’re eventually going to follow them? Or you don’t think they have secularized?

BROOKS: No, I do think they have secularized. I think Western Europe and Japan have secularized. I think much of the rest of the world has not, and that much of the Western world is still . . . Africa, the Middle East . . .

COWEN: But wealthy countries — we seem to be the only religious one.

BROOKS: Maybe we’re the nation with the soul of a church. I guess my basic belief is that you either have a religion or some sort of religious substitute, that people are innately soul driven, spiritual creatures. And then imagine that people really suffer when they have a sense their life has no transcendental purpose and meaning.

My observation is that people — over the centuries, we get secular. We were super secular in 1913. But the human being is such that there’s a spiritual hunger there that seeks outlets. And when the church does really bad answering that outlets, which most churches have done over the last 50 years, people drift away. But then somebody invents something new, and the drive for transcendent experience leads people back.

COWEN: What do you think of the view, common among Muslim theologians, that Western liberalism is, in some sense, a footnote to Christianity? That we have a relatively individualistic religion. It’s “individual as victim” rather than “might makes right.” Western liberalism is an offshoot of that. And it relies on Christianity for its sustenance, intellectually, spiritually, and otherwise.

BROOKS: I would say Judeo-Christianity. The idea that we live in a covenantal society, that we co-create with God, is a Jewish idea. We were just talking about Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, who has a beautiful book called The Home We Build Together. It’s about covenants. And a lot of it is, what’s the difference between the purely liberal view of human arrangements, which is contracts, and a religious view of human relationships, which is covenant?

His argument is that contracts are what we do for our individual benefit. A contract is about interest. But a covenant is when we make a promise to each other that transforms our identity. And when we make a covenant, one with another, whether it’s a marriage covenant or to our nation, we serve the relationship more than we serve ourselves.

That’s why people are willing to die in a battlefield. That’s why people are willing to risk their lives for their children. And it seems to me the more covenantal relationships we’re involved in, the more our life feels fulfilled.

COWEN: We often hear the term “religious extremism” used as a criticism, but doesn’t, in a sense, any serious religion have to be extreme in some way?

If one believes that Christ is, however you want to phrase the belief about the Trinity, but the Son of God or whatever the claim is, that’s almost by definition a radical, extreme claim. Or that the Koran literally has come down to us from God. That has to be an extreme claim to be interesting, right? So, is there such a thing as religious extremism as a negative?

BROOKS: Yes.

[laughter]

COWEN: And what is that?

BROOKS: The religious people I know and admire . . . You go into some places and it’s like, “Yeah, God told me to buy french fries. He didn’t want the potato chips that day.” I’m like, “Who are you people?” I don’t know anybody who I respect who God talks to in that way. Most people I know, God appears — and these are people who have devoted their lives to religion — God appears occasionally, and then you sort of wonder about it.

There’s a guy named Frederick Buechner, who’s a novelist and a theologian. He said, “If you wake up every morning and say, ‘I feel God right next to me,’ I really don’t recognize you. But if you wake up one out of 10, and you feel some presence, and that presence comes with infinite laughter, that’s sort of how I feel it.”

A friend of mine is a great poet named Christian Wiman, who is up at Yale. He says he occasionally has moments of transcendence. The way he describes it, it feels like poetic inspiration. Then he says, “The rest of the time I don’t feel much, but I try to stay faithful to those moments.”

There’s a great scene, I’m going to hopefully not butcher it entirely. He was in Prague with a girlfriend, and he was sitting there working on his poetry on the dining room table, and I think it was a falcon lands on the windowsill on the other side of the window. And he looked at the falcon. The falcon didn’t notice him.

So he called to his girlfriend, who was in the shower. And she comes out, and she’s naked, dripping wet, and they stare at this falcon. And the falcon turns and locks eyes with them. And they’re just sort of awed by the experience of this contact with nature. And she whispers to him, “Make a wish, make a wish.” And he said, “I just was in wishing for a moment that moment would last forever, and it went away.” And he describes that as just this moment when sort of reality spills outside its boundaries.

Most religious people I know have those moments, and they get a sense of grace or of God’s presence. But then it goes away. So if you’re filled with doubt, and filled with doubt about your own interpretation, which is pluralism, then you’re not an extremist. And to me that’s the only civilized way to be religious.

COWEN: But the religions that motivate people — they seem to be based on extreme claims. On the other hand, we’re both technocrats of a sort and pragmatists, and we’ll look at the evidence and change our mind about policies.

If you have religion, and then you have your technocracy, how is it that you circumscribe the two and keep them apart? Because the people who are motived by religion think the supposedly extreme religious belief has a say about the areas where we want to be technocrats.

BROOKS: Well, they make extreme claims. I’d call them . . . they make supernatural claims, which is a hard barrier to get over, I grant you. But I would say — and this is why I read a lot of religious writing: it helps me do my job better.

The central claim of religion is that, as a friend of mine, Jerry Root, puts it, is that reality is iconoclastic. There’s something weird extra there. The way I would say it is that we all have souls. There’s all a piece of each of us, which has no weight and has no color and has no size and shape, but is in us, and it gives us infinite dignity, and it causes us to want to lead good lives. And that slavery is wrong because each person has a soul, and slavery is an obliteration of a soul. And that rape is wrong because rape is not just an assault on a bunch of physical molecules, but it’s an obliteration of another human being’s soul.

If I don’t have that concept of soul, it’s very hard for me to do reporting. It’s very hard for me to understand how human beings are and why atrocity is wrong. So I’d say that’s a very empirical . . . I would find it very hard if I’m out covering a story — something that outrages me or something that delights me — if I didn’t see the people I was covering as essentially spiritually driven natures, I just think the whole story would fall to pieces. I find it, not empirically in a statistical way, but empirically helpful, as a way to see reality.

COWEN: You’ve described yourself at times as religiously bisexual. What do you mean when you say that?

BROOKS: I need my own bathrooms.

[laughter]

I grew up in a Jewish household. And when you grow up in a Jewish household and Jewish family, kept Kosher all those years, you read the Passover Seder, and you feel deeply how stories enter you and the story of Judaism. And I feel so Jewish. A lot of my friends are Jewish. My jokes are Jewish. My style is Jewish. And so you feel that you’re just deeply and irrevocably embedded in that story.

At the same time, I went to the school that probably had the biggest influence on me was called Grace Church School, which if anybody goes to the Strand Bookstore in New York, it’s just really next door. A beautiful church on Broadway. I was in the choir, and so I sat in chapel every day.

Then I went to an Episcopal camp for 15 years, and then I read Reinhold Niebuhr, and then I fell in love with Saint Augustine, and somehow you find that story settling into you. And so I feel more Jewish and more attached to the Christian story than ever. Both. So that’s why I’m bisexual.

[laughter]

COWEN: And do you think Jewish or Christian readings of the Book of Exodus are deeper and more insightful?

BROOKS: [laughs] Which friends do I want to offend?

[laughter]

I think the Old Testament Torah is amazingly complex, and I would say it’s amazingly interesting, and there are just so many characters. Frankly, the New Testament’s about one guy essentially, so it can’t compete. If we’re judging these on novelistic grounds, maybe that’s not the right criteria. I think the Holy Spirit might have introduced a few more characters, liven up the plot. [laughs]

I would say I get a little tired of Jewish theology when it gets pedantic. How many grains of rice can be in your bowl of whatever, and Passover . . . But some of the Jewish writing from Martin Buber and Abraham Joshua Heschel and others on the Book of Exodus are amazing.

The Christians do better on love. [laughs] I’ve read Christian books about Ruth, Naomi, and Boaz which strike me as just a greater appreciation. Maybe Jews got a little too cognitive. I don’t know. These are my off-the-top-of-my-head, extremely dangerous, self-destructive generalizations I’m making. If anybody takes the last three and a half minutes too seriously, I ask for forgiveness.

[laughter]

COWEN: Let’s say Elon Musk is right and we will be able to settle distant planets. Should we choose people all just from one religion or one country? Or how pluralistic should we make the settlement? Keep in mind you’re an American, and the early settlements here were fairly narrow, right? We had a number of waves, but each one was pretty well defined in some way, so you have Puritans or you have the Spanish.

BROOKS: Yeah, the Puritans — I actually have a lot of respect for the Puritans. They don’t strike me as the most fun group to settle Mars with.

[laughter]

They were actually way more sexualized than we think. We sort of narrow them down unfairly. I blame Henry Miller or Arthur Miller.

[laughter]

My bias, especially these days, is for infinite diversity and integration. In a weird way — and I really don’t understand this — all the fun in life comes from integration. That’s from integrating one group of people with a radically different group of people, and somehow it’s become uncool to be for integration.

We’re all for our separate little communities and the purity of our cultures. But the most enjoyable times I’ve had are with people completely unlike myself, where I can learn about what . . . I mean, your whole omnivorous brain is one vast testimony to the power of cultures clashing and joining.

COWEN: Why have so many young men stopped even looking for work? What has happened to aspiration in our culture?

BROOKS: You know these . . .

COWEN: I’m asking you, right?

BROOKS: [laughs] I’m a pundit, so I have to come up with answers that I’m not sure I feel qualified.

We’re all driven — and I’m again speculating because these are unusual questions — by complexes we don’t understand. If you have six adverse childhood experiences in your life — some sort of abuse, some sort of loneliness, some sense of betrayal — it’s hard to get a sense of self-agency.

Everything’s recoverable, but attachment patterns, early trauma, a sense of if you’ve been betrayed enough, then long-term thinking doesn’t make sense. So I would say the desire to not aspire — and you can rationalize that away — probably comes from some sort of wound, an injury, in people’s lives.

After I missed the Trump thing so badly, I traveled around the country for 18 months, and I’m still doing it and always talking to Trump voters and other voters. The amount of wounding and amount of sense of betrayal, high levels of distrust, high levels of feeling “Everyone else is getting ahead and I’m falling behind,” I found especially for young people in their 20s, even people with sterling educations.

The 20s have become for many a brutal time, that they don’t quite know what their purpose is in life. They don’t quite have the skills to get out of the wide-open options. They’re afraid of closing off options because they’re not really quite sure who they are. We’ve produced a society that’s made being 25 phenomenally difficult, in part because you’re in the most supervised childhood at human history until 21, and after that, you’re released into the complete void.

We’ve produced a society that’s made being 25 phenomenally difficult, in part because you’re in the most supervised childhood at human history until 21, and after that, you’re released into the complete void.

You’re not going to get married for another 12 years. You’re not going to settle into your career. I’ve come to notice it in my students. I’ve come to call it the Telos Crisis, the loss of sense of purpose. When you get the setback in your mid-20s, you don’t quite know where your life is, you haven’t discovered it, you haven’t found some calling that just seizes you, and it can be pretty rough.

Nietzsche has a phrase: “He who has a why to live for can endure any how.” That if you know what your long term is, then you can endure the setbacks, but if that hasn’t become clear to you, then the setbacks are super hard. And I noticed it in the rising depression rates, the rising mental health problems, the rising suicide problems. We’ve sort of left people in a very unstructured experience after age 21.

I just gave this commencement talk at Butler University, couple days ago. And commencements are happy, and I was like, “Your life is going to suck in three years.”

[laughter]

BROOKS: I’m not sure that was the right spirit for that occasion.

On the golden years

COWEN: Our mutual friend, Jonathan Rauch — he has a book where he argues quite persuasively, I think, that people tend to become considerably happier after age 50. First, what do you infer from this? Second, since often children are leaving the house then, does this not mean that a bit more loneliness would be a good thing?

[laughter]

COWEN: And maybe, aren’t the main determinants of your state of mind just heritability, the basic level of wealth in your society, and how old you are?

BROOKS: No.

COWEN: No.

BROOKS: Well, Jonathan Rauch, he’s absolutely right. There’s a U-shaped curve. People are happy in their 20s, and they sort of bottom out at 47, which to me is having teenage children.

[laughter]

He has more complex things, but then they rise up, and some of it is straight biological. If you give people experiments where you ask them to look at a crowd of faces, young people look at angry faces; they go toward threat. Old people, their eyes just fixate on the happy faces. They just perceive reality as a more friendly thing. So that’s one of the reasons.

He’s even got data on . . . apparently, baboons also have a U-shaped curve, that they’re happy in young baboonhood. Then they get middle aged, baboonhood stinks. And then upper to old age baboonhood. I don’t know how they measure this.

[laughter]

But to me, I guess my answer would be, it’s again quality of relationships. Quality of relationships correlates extremely well with happiness levels. If you join a club that meets once a month, that produces the same happiness gain as doubling your income. So if relationships are the thing . . .

And I would say that people get better at living, that in their 50s and 60s they get out of their own way. The sort of monster of self-regard diminishes. How am I doing? How am I doing? What do people think of me? After a certain age people stop caring, and that’s the recipe for happiness.

[laughter]

BROOKS: And then I notice — and I’m going to write about this, I hope — the people I talk to, especially over 70, their life has this shape, which I’ve come to think of as the two-mountain shape. They got out of their education, and they figured, “Oh, that’s the mountain I’m going to climb up.” And there’s a career they imagine. There’s a family they imagine. Then they achieve that success and find it unsatisfying. Or else something really bad happens, and they suffer. They’re at the valley, and they realize, “Oh, that actually wasn’t my mountain.”

There’s a second mountain, and it happens often in their 50s and 60s. The second mountain tends to be more about community service. It’s more internal, less external. The first mountain is more building up the identity and the ego. The second mountain is sort of shedding it all, and it’s more about pouring back.

You meet person after person who built a career, and then they went off and became a teacher. They went to Tibet and meditated, or they dedicated their life to some cause. And that second mountain is a more spiritual mountain, but it’s just a happier mountain. So I think people just learn lessons as they get older, and they get better at living.

COWEN: In an age of supposed revelations about Silicon Valley and so-called Facebook scandals, why don’t Americans seem to care more about their privacy? And in your view, is this actually a good thing that we’re not so worried about it?

Not many people have quit Facebook, right? There can be a big ZIP file of information about you out there. There’s not actually any great protest in the parks of Arlington that I know about. Some media people, some intellectuals, but otherwise, no.

BROOKS: Yeah, that’s my observation. Mark Zuckerberg came through town, and all the hearings were about privacy. And yet I don’t really . . . I hear a little about that.

To me, the problem with Facebook is the fact that, especially for 16-year-olds, the more social media you use, the more depressed you’re likely to be. That’s the big problem with social media, not the privacy invasions. I think people assume that that’s their business model, and the stuff they find out about us is trivial — my wife and I, we were going to decorate our house with one of those little barrels, like a decorative barrel. And for the next six months, whenever I logged on to any website, I had to look at a damn barrel.

[laughter]

Because they thought I was going to buy a barrel, and so we decided we didn’t want a barrel. Is that really . . .? Okay, so that’s an invasion of my privacy. But I’m sure there are other privacy experts who are more alarmed, but I haven’t seen a massive pain caused by this invasion.

On things under- and overrated

COWEN: Might you be game for a quick round of overrated versus underrated?

BROOKS: As I said, this is the most intimidating interview of my life. This is the most intimidating part of the intimidating.

COWEN: But I think these all will be easy.

BROOKS: Okay.

COWEN: The Bruce Springsteen album, Born to Run, is it overproduced? Or is it his best work?

BROOKS: It’s overproduced and some of it is his best work.

[laughter]

BROOKS: It’s a wall-of-sound style, and he . . . It’s like a lot of artists. He got more spare and more simple as he went along. But for a guy who was at the peak of his creativity, it was an explosion of creativity.

COWEN: The Bruce Springsteen double album, The River, which is underproduced, has a very nice flow, but maybe not so many truly great, wonderful, amazing songs. Underrated or overrated? The River.

BROOKS: Everything by Springsteen is rated extremely highly, and everything by Springsteen is underrated.

[laughter]

COWEN: And what is it that you would point our attention to in Springsteen that is underappreciated by most others?

BROOKS: The crucial moment for me in Springsteen — he has two albums. He gets a three-record deal. His two records are bombs, the first two. Greetings from Asbury Park, who, for those who can see, is at our feet here. And then The Wild, the Innocent, and the E Street Shuffle. They’ve failed commercially, and the company’s going to cut him loose.

Then he comes out with Born to Run, which is a massive success. He’s on the cover of Time and Newsweek, so he has made it. The next logical step for any artist in the commercial sphere would be to go big. I’ve just made it out of New Jersey. I’m going big. I’m going to go for the big album that’s going to really make me a superstar.

Instead, partly for legal reasons, he takes four years off, and he goes down back into his roots of these New Jersey small towns, and he writes an album called Darkness on the Edge of Town, which is dark, small, simple, and really local, going back into his landscape.

And that was an amazingly creative and courageous decision. I saw Springsteen in Madrid about four years ago. I’m surrounded by 65,000 Spanish kids, and they’ve got t-shirts with all the pieces of landscape from that album, Highway 9, the Stone Pony, all these little items from the New Jersey landscape that Springsteen came about.

And that’s a lesson for an artist, and it’s like the Faulkner lessons, like a lot of artists. If you go to the power of your particular and build the landscape there, the audience will sense the authenticity of what you’re doing. You’re exploring your own stuff, and they will come to your landscape and live in your landscape with you.

There was a moment in that concert in Madrid where he’s singing, “I was born in the USA, I was born in the USA.” And 65,000 Spanish kids are singing, “I was born in the USA. I was born in the USA.”

[laughter]

I’m like, “No you weren’t. No you weren’t.”

[laughter]

But to me, one of the great ironies of Springsteen is that he embraces, in theory, the ethos of rock and roll. “I’m on the road, I’m rebelling, I’m getting out.” The guy now lives 10 miles from where he grew up. The ethos was “Get out,” but his genius was to go deep and plant roots and stay within his roots.

And that was a great courageous artistic decision, which I notice a lot of artists making that decision. Lin-Manuel Miranda has one of those moments where you reject the easy success, and you go back to who you are.

COWEN: Let me tell you some of my reservations about Bruce Springsteen, and let’s see if you can talk me out of it.

[laughter]

BROOKS: No, I was willing to trample over the New and Old Testaments, but now we’re getting onto holy ground here.

[laughter]

COWEN: If I think of his sources, like Roy Orbison, Gary and the US Bonds, Eddie Cochran, they’re almost completely American. And you’ve stressed virtues of integration; they’re strongly white. There’s a kind of, I hesitate to say monotony, but there’s a sameness of rhythm in a lot of Bruce Springsteen.

If I say instead, well for me, kind of foundational American musicians, singers, songwriters, I would look to Paul Simon who’s more global, Bob Dylan who’s more religiously bisexual as a stronger link to black culture. And I would put Springsteen as less important than them. What would you say to talk me out of that?

[laughter]

COWEN: He’s a kind of nationalist, isn’t he? And you’re a cosmopolitan.

BROOKS: [laughs] Bruce Springsteen is Donald Trump and Steve Bannon rolled into one.

[laughter]

He’s not a cosmopolitan, actually; I think you’re right about that. I would point to some influences that . . . you know, Sam Cooke and some others. B. B. King probably, some of the blues guitarists. A lot of the 1950s R&B singers were big influences. He really grew up by the ’55–’65 era, and I would say he drew from white and black in that era. But I don’t know how to compare him to Dylan. Dylan is not my cup of tea a lot of time, especially later Dylan.

But I would say that, as an artist who’s exploring his own issues and is relentlessly not performing, but is being relentlessly honest with the issues that really trouble him and sent him to analysis for 45 years. He’s a pretty honest guy, and he’s got a lot of good passages in his memoir, which is a really good memoir. It’s a memoir of somebody who has been in analysis all his life because he’s talked it all through. One of them is his evaluation of his own voice, which is a medium-quality voice. But he says, “I do sing truly to what I’m feeling,” and he’s very transparent.

I had a chance to meet him a couple times, once for an extended period. He’s amazingly shy, and when you see him on stage, you can’t believe you’re seeing the same human being. A lot of writers are like this. They’re only fully themselves when they’re in the process of writing. So he’s someone who’s honest about what he’s processing and then throws it out.

And the key to good performance when I go to a concert or the key to public speaking is, are they willing to throw themselves out into the audience and hope the audience will pick them up? And if you want to see a good speaker or a good musician, they always have that quality, that “I’m helpless here, you got to help me here.” And he does that every time.

COWEN: Walt Whitman, not only as a poet, but as a foundational thinker for America. Overrated or underrated?

BROOKS: I’d have to say slightly overrated.

COWEN: Tell us why.

BROOKS: I think his spirit and his energy sort of define America. His essay “Democratic Vistas” is one of my favorite essays. It captures both the vulgarity of America, but the energy and especially the business energy of America. But if we think the rise of narcissism is a problem in our society, Walt Whitman is sort of the holy spring there.

[laughter]

COWEN: Socrates, overrated or underrated?

BROOKS: [laughs] This is so absurd.

[laughter]

With everybody else it’s like Breaking Bad, overrated or underrated? I got Socrates.

[laughter]

I will say Socrates is overrated for this reason. We call them dialogues. But really, if you read them, they’re like Socrates making a long speech and some other schmo saying, “Oh yes. It must surely be so, Socrates.”

[laughter]

BROOKS: So it’s not really a dialogue, it’s just him speaking with somebody else affirming.

COWEN: And it’s Plato reporting Socrates. So it’s Plato’s monologue about a supposed dialogue, which may itself be a monologue.

BROOKS: Yeah. It was all probably the writers.

COWEN: A few questions about politics, but of course, feel free to pass if you wish. Should Donald Trump win a Nobel Peace Prize?

[laughter]

BROOKS: No. The Nobel Prize for Literature maybe, but no.

[laughter]

COWEN: Is the Wilsonian foreign policy still feasible, given that our GDP relative to global GDP will just keep on falling?

BROOKS: I’m an idealist in foreign policy, but Wilson is too idealistic for me. I’m more realistic. I think a Reaganite foreign policy is still possible, which urges democracy promotion, human rights abroad, but is not quite thinking that we’re going to solve human evil within three years.

COWEN: You argued in a recent column that the anti-Trump movement basically has failed. What could it or should it have done better or different?

BROOKS: It should have understood where Trump supporters were coming from. And I’m as guilty about this as everyone. You know, when I get pushback from Trump supporters, which is frequent, it’s because they don’t feel respected and heard. A realistic understanding of why people voted for Trump, and then a realistic argument about why he failed on those grounds rather than the grounds that I happened to be offended by, Charlottesville and all the rest.

COWEN: If you think about what is coming next in American politics, one view I sometimes hear is we tend to elect presidents who are a reaction against the previous president. So Jimmy Carter was, in a way, a reaction against the era of Watergate. Reagan was a reaction to Jimmy Carter. You know the story, of course. There’s a kind of reversion to a mean.

Another view is that every now and then, just things change, and they don’t go back to how they were. So the postwar era, those presidents do seem fundamentally different from a lot of the knuckleheads we had in the mid- to late 19th century. So here we are in 2018 — which of those two models or some other model do you think does best?

BROOKS: Yeah. I think the reaction . . . You can react in two ways. The reaction I would hope for is to some boring manager. I read a book in 2015 on humility. And then 2016 happened, and Donald Trump gets elected. So my reaction was, “Well, that worked.”

[laughter]

Then the reaction will be, okay, we’ve got a narcissistic blowhard in the White House, we’ll go back to . . . I could use like a boring manager, like Mitch Daniels, who was governor of Indiana and now president of Purdue. When he got into office as governor, the line at the DMV was an hour and 20 minutes. When he got done, it was eight minutes. And I’m like, for president, I’ll take that. That’s what I’d like, just somebody to manage things.

COWEN: There’s a DMV in this building, by the way.

BROOKS: Oh really? I’ll test . . .

COWEN: If you need to take care of any of your business.

[laughter]

BROOKS: Yeah, I don’t live in Virginia, sadly.

So he was five foot six, low to the ground, in touch with the people.

[laughter]

That was one reaction. But the more likely one I think is, Trump was a swing to a certain sort of paleo Pat Buchanan, right? And I think it’s a little more likely that we’ll get the swing to a paleo left, and that we’ll get the Trumpism on the left, which will be pretty socialistic and pretty progressive left.

COWEN: But in terms of the boring manager, why should we want that or why should we think it’s possible? If the anti-Trump movement went wrong by not hearing the people who feel aggrieved, is it possibly the case those people can never feel that a boring manager has heard them because all he’s going to do is go off and manage something in a boring way?

BROOKS: [laughs] What I observe — and this is a book I’ve just finished reading by James and Deborah Fallows called Our Towns, and one observes this — is as you travel around the country, our national politics stinks to high heaven. A lot of local cities are doing well. And they point to Greenville, South Carolina; Fresno, California; Eau Claire, Wisconsin; Nashville. Detroit is doing reasonably well.

Those cities are all run by people who say, “There’s all those culture war, cable TV issues — we’re putting that nonsense aside, and we’re just going to talk about . . .” I was with this guy, mayor of Detroit, Mike Duggan, and he talked about where to put the lamp post, where to cut the grass, the basic management issues. The cities that are doing well are run by people who do business, private-public partnerships. They focus on community colleges, and they produce measurable results for working-class Americans.

To me, all you have to do is take the success of all these mayors at the local level and try to nationalize it. And that’s completely plausible to me. When you look at times of American history when we have recovered, turned around the social decline without the benefit of war, it’s like periods from 1890 to 1910, and generally we take some local, series of local movements, and we merge it into a national movement.

In the 1890s, we had all these civic organizations that grew up all at once. We had the Boy Scouts, Girl Scouts, the Boys Clubs, the Girls Clubs, the temperance movement, the settlement house movements, the NAACP, the unions. They all grew up in five years of each other. Then they joined together eventually and formed the Progressive Movement, and they cleaned up government.

So to me, if you want to look how America changes, look around what’s happening locally and figure it’ll probably nationalize at some point.

COWEN: The earliest appearance of David Brooks on video, I believe, is still on YouTube. You’re a young man and you’re challenging Milton Friedman on the Chrysler bailout. You remember this encounter?

BROOKS: [laughs] Sadly, I do. It’s like one of those early traumas that will live with me forever.

[laughter]

COWEN: What was it like having Milton Friedman lecture you about the Chrysler bailout?

BROOKS: I was a student at the University of Chicago, and they did an audition, and I was socialist back then. It was a TV show PBS put on, called Tyranny of the Status Quo, which was “Milton talks to the young.” So I studied up on my left-wing economics, and I went out there to Stanford. I would make my argument, and then he would destroy it in six seconds or so. And then the camera would linger on my face for 19 or 20 seconds, as I tried to think of what to say.

And it was like, he was the best arguer in human history, and I was a 22-year-old. It was my TV debut — you can go on YouTube. I have a lot of hair and big glasses. But I will say, I had never met a libertarian before. And every night — we taped for five days — every night he took me and my colleagues out to dinner in San Francisco and really taught us about economics.

Later, he stayed close to me. I called him a mentor. I didn’t become a libertarian, never quite like him, but a truly great teacher and a truly important influence on my life and so many others. He was a model of what an academic economist should be like.

COWEN: What do you think of the Chrysler bailout now?

BROOKS: I not only support the Chrysler bailout, I support the Obama bailout of GM, which I was against at the time.

I will say one other thing about Friedman. Early in my life, when I was 23, I got this little fellowship at the Hoover Institution. And at 3:30, you would have cookies, and you could go to Milton Friedman’s table with all the economists at Stanford or Sidney Hook’s table with all the philosophers. So some days I would go hear Hook. And I remember he was a great philosopher, and he did an hour-and-a-half discussion of the problem of evil, which was thrilling.

Once I was sitting at the Friedman table, and I was making some dumb argument, I’m sure. And some other economist at the table ripped me to shreds, but I didn’t understand what he was saying because it was all jargon. And I finally just said, “I really don’t know what you just said. I don’t understand, I’m sorry.” And Friedman laughed, and he was totally on my side.

[laughter]

I felt great gratitude to him for leaping to my defense, and he was an economist who could speak without jargon and sort of a model of that. But that was an act of great charity, which I remain grateful to him for.

COWEN: And I didn’t feel you lost that early exchange with Friedman. It seemed to me to be a draw, that you had good arguments, and he had good arguments, and then time was up.

BROOKS: Oh, good. Well, I beat Milton Friedman, or at least drew even. Where’s my Nobel prize?

[laughter]

On the David Brooks production function

COWEN: Now I have a few questions for what I sometimes call the David Brooks production function about you. Obviously, you’ve written numerous best-selling books, been a journalist for the Wall Street Journal, long-standing columnist for the New York Times. How you work is what I’d like to ask about. How would you say you keep yourself motivated? Because I’ve written for many years, and getting up every morning and having to do things, how do you keep that live and active for yourself?

BROOKS: I read a book when I was seven called Paddington Bear, and I’ve written pretty much every day since then. People know to get out of my way before I write for two hours in the morning; that’s just how I live. I just do not stop writing.

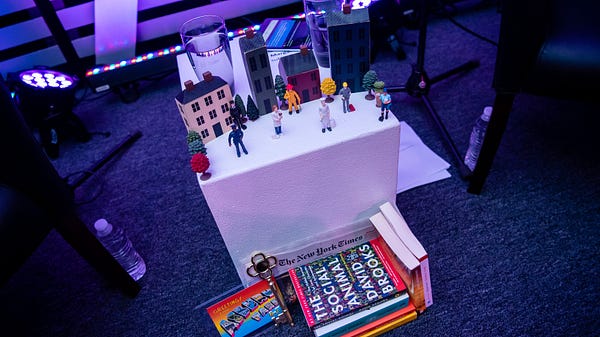

The thing that’s distinctive about my style is that my brain has very bad memory, so I have to write everything down. Then I think geographically. For each column I’ll have 200 pages of notes and then a bunch of things I’ve written to myself, and I lay them out on the floor of my living room in piles, and every pile is a paragraph in my column. The column is 850 words, and I’ll have 14 or 15 piles. I’ll pick up a pile, write it, throw the pile out, pick up another pile of papers.

The thing that’s distinctive about my writing style is that my brain has very bad memory, so I have to write everything down. Then I think geographically. For each column I’ll have 200 pages of notes and then a bunch of things I’ve written to myself, and I lay them out on the floor of my living room in piles, and every pile is a paragraph in my column. The column is 850 words, and I’ll have 14 or 15 piles. I’ll pick up a pile, write it, throw the pile out, pick up another pile of papers.

Writing for me is not typing into the keyboards. It’s crawling around on the floor, organizing my piles. And the lesson for my students, which they ignore, is that your paper should be 80 percent done by the time you sit down and type it because writing is about structure and traffic management. If you don’t get that right, everything else will flow badly.

If something’s not working, judges have a saying, “That opinion won’t write.” They thought they knew what they believed, but then they started writing, and it just wasn’t flowing. Don’t try to fix it; start over with a new structure. So to me, I crawl. I write by crawling around on the carpet.

COWEN: And writing aside, just learning, keeping on learning through life, there are plenty of obvious pieces of advice, like read books, talk to smart people. What do you feel you can tell us that maybe we haven’t already thought about already, how to keep on learning through life?

BROOKS: I just read the Marginal Revolution blog and steal as much as possible unscripted.

[laughter]

The one virtue of this job is that you have to come up with a new idea every three days. It may not be a good idea. I find I’ve written more than 1,000 columns, but if I write a bad one, then I feel really bad. I feel really humiliated. And if I write a bad one, and Ross Douthat and Bret Stephens write good ones, I feel really bad.

[laughter]

I’m trying to think of other than the obvious. I go to conferences; I don’t learn that way particularly. I learn by reading. I’m always reading — not as much as you, but 50 percent of you maybe.

COWEN: What would it take for you to pack up and move to rural China for a year, to live there and write about what that’s like? Or a month even?

BROOKS: That’s actually kind of attractive.

COWEN: [laughs] The food is good.

BROOKS: The food is good, and it would be life altering. I know it would be good because what’s another year in DC?

I think I would say the action is here. I mentioned James Fallows before, but called “The Fallows Question,” which is, Jim Fallows in the ’80s, he went to Japan, then he moved to China. He wrote about Iraq. Each decade, he’s more or less picked the spot where the action is.

So the question is, if you could live anywhere in the world where history is being made, where is the action? And Fallows now thinks it’s like Fresno, California. But I would make the argument that Washington is where the action is right now. So living here actually has some good utility even if it seems a little boring.

The second thing is, part of my career, rightly or wrongly, is based on the view that politics . . . Our conversation is overpoliticized and undermoralized. We write too much about politics and not enough about relationship and truth and yearning for goodness and meaning. So what I try to do with my little column is sort of shift the direction a little in more that sort of meaning, purpose, culture direction.

COWEN: Do you have a work habit dysfunction that you’re willing to confess to?

[laughter]

BROOKS: I have the same one everyone else has, which is checking my phone every 90 seconds. I am a big pen chewer. I don’t know if that counts as a real dysfunction. I feel I should come up with something more dramatic: I chew pens and shoot heroin at the same time.

[laughter]

COWEN: A young person comes to you and says, “I would like to be some version of the next generation of David Brooks,” which won’t be exactly what you did by any means. Other than the trivial advice — work hard, talk to smart people, whatever — what would you give that person in the way of advice to guide them?

BROOKS: Well it used to be you would . . . The career path was kind of ordinary. You became assistant editor of the National Review or New Republic, and then you moved up the opinion food chain.

Then the Ezra Klein model seems probable. You go online, you do work nobody else wants to do so somebody pays attention to you, and then you get well known for being a smart person who’s willing to work hard. I think that’s probably still the way to go. The obvious lessons are say yes to everything. You don’t know what’s going to lead to what. So when you’re 24, say yes to every opportunity. I was a movie critic, I was a foreign correspondent. That was a very useful thing to have. I wrote about El Salvador. I’ve still never been to El Salvador. Just somebody asks you to do something, say yes.

COWEN: I’m happy to bring you, by the way.

BROOKS: I’m happy to go.

COWEN: I won’t ask because you’d have to say yes. There is a direct flight.

BROOKS: And the other thing is . . . This was Richard Holbrooke’s advice to young people, which was, “Know something about something.” You’ve got to have a body of information to bring to the table.

I’m writing a book on this, so I’m filled with random bits of advice right now. But there’s a guy, friend of mine named Fred Swaniker, who grew up in Africa, and his mother was a teacher, and he was educated here. He founded a school in South Africa called the African Leadership Academy, and he was trying to figure out what to do with the rest of his life. And he said — which is true advice — when you’re thinking about what to do with your life, don’t say what do I want to do from life? Ask what is life expecting of me? This is the Viktor Frankl question.

What problems are around me that are really calling me? And then, one, is it a big problem? You got to fall in love with a big problem because if you have some human capital, you might as well go for the big problem. Two, is it a problem your life history has made you uniquely qualified to serve? So Swaniker decided education in Africa is the big problem, and there need to be more universities for all of Africa.

And he said, “Actually, I’m uniquely qualified to do that because I did grow up across all of Africa. I was an educator; my mom was an educator. I did have the advantage of an American education. I did go back and form a Pan-African high school. So I’m going to start universities.” He’s already started one in Mauritius, and I think he’s on schedule to start another 10 or 15 universities across Africa, which is an audacious goal, but it’s one that he was uniquely qualified to serve.

Fred Buechner, the novelist who I mentioned before — he has the most famous phrase of avocation, which is, “Find the spot where your deep gladness meets the world’s deep need,” so something you intrinsically love doing and match it with some deep problem that’s out there.

COWEN: Last question before I turn to the audience and the iPad for questions. What is indeed your current and next project?

BROOKS: So it was about commitment making. The theory of the book when it started was that each of us makes four big commitments in the course of our lives— most of us make these commitments to a spouse and family, to a vocation, to a community, and to a philosophy and faith. And the fulfillment of our lives depends on how well we choose and execute these commitments.

So how do you do that? And what are examples of people who are great at making commitments? And what is a commitment? My favorite definition of commitment, by the way, is falling in love with something and then building a structure of behavior around it for those moments when love falters. So Jews love their God but they keep kosher just in case.

[laughter]

BROOKS: You’ve got to build the structure. And now I think that I’m probably going to call it When You Give Yourself Away. The argument is, everyone says, “Serve something larger than yourself.” That’s the cliche of the moment. But what does that actually mean? How do you actually do that? So the book is an attempt to look at people who’ve actually done that. Not me, but other people who’ve done it, and what are the lessons we can learn from their lives?

COWEN: David, thank you very much for all of your wisdom.

Q&A

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Hi. I kind of observed, since you’ve moved to the Times, and also I might say the same thing for Bret Stephens, that I never feel like I’m reading a conservative anymore. Do you feel like the Times has changed you? Or are they not letting you be conservative or . . . And then am I correct that you’re moving a little bit to the left?

BROOKS: Yeah. Well, if I write a conservative sentence, Krugman hits me with a ladder…

[laughter]

No, first thing to say is that nobody supervises us. We are given total academic freedom. We have copyeditors in New York, but we really don’t consult with editors. We basically write the column and send it in. So for good or ill, it’s all us. The second thing I would say is, if you read my stuff in the Weekly Standard, I was writing this Hamiltonian, Teddy Roosevelt style of Republicanism back then, which I still think I’m writing.

The third thing to say is, I think events have pushed me away from a more pure free-market view especially, because I think the structures of the economy have become more evident, the structural flaws of the economy. And that I’ve become a little more tolerant of government intervention as inequality is wide, and as working class has been left behind, as society is falling apart.

So, I probably have drifted a little to the left as the party has drifted in a more populist, nativist direction, but I don’t think I’ve moved all that much. I’m still basically your Teddy Roosevelt, Alexander Hamilton Whig.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: So, much has been written about failure and why it’s good, but not a lot of it is practical or useful. What advice would you give to, say, a young recent college graduate about how to fail and even how to suffer well?

[laughter]

If you’re Steve Jobs, J. K. Rowling, or Denzel Washington, failure is awesome. But for most people, failure just sucks, and I wouldn’t do it.

BROOKS: Steve Jobs gave a famous commencement address at Stanford on the importance of failure, and J. K. Rowling gave a famous commencement on the importance of failure, and Denzel Washington gave a famous commencement on the importance of failure. So if you’re Steve Jobs, J. K. Rowling, or Denzel Washington, failure is awesome.

[laughter]

But for most people, failure just sucks, and I wouldn’t do it. Now as for suffering, suffering comes whether you want it . . . I wrote a little section in my last book about the value of suffering, and one of my students came up to me and said, “Well, how can I find some suffering?”

[laughter]

BROOKS: I’m like, “Don’t worry, it’ll find you.” And I think that the lessons, the classic lessons are the people who suffer and grow from suffering are able to turn their moments of suffering into a story of redemption.

If you ask somebody, “What made you who you are?” nobody ever says, “Oh, I went to Hawaii and I had an amazing time. That was really the transformative event of my life.” But a moment of suffering is usually what they point to, or struggle, and what they do is they . . .

There’s a Paul Tillich phrase that what suffering does is, it introduces you to yourself and reminds you you’re not the person you thought you were. And then he says, “What it does is, it carves through the floor of what you thought was the basement of your soul, and it reveals a cavity, and then carves through that floor and reveals a cavity below.”

So moments of suffering reveal the deepness of a person the way nothing else does. Then I think you realize the only thing that can fill that depth is a spiritual food and not a material food, and people want to fill that depth with something.

I have two friends, for example, who lost a child. Nobody says, “Well, we grieved for two years. Let’s go out and party, and let’s be happy.” They want to turn that moment of suffering into a cause and a precondition for service.

So they created a charity called Hope for Henry about their child, in honor of their child, so other children wouldn’t have to suffer from what Henry suffered from. They turned a moment of suffering into a redemption and meaning, and those who don’t turn their moments of suffering into that kind of redemptive narrative, they can really shrivel.

But I find most people, those moments of suffering deepen them, spiritualize them, and they . . .

What I talked about — that monster of self-regard — it sort of crashes through the ego. The people who’ve been through deep suffering, it sort of breaks the ego and they are less self-obsessed.

There’s a guy named Henri Nouwen who I read, and I’m not sure I agree with this. He says, “When you’re in a moment of suffering, your instinct is to get out, but sometimes you need to stay in that moment of suffering to see what it has to teach you.” I’m not sure about that. I would get out. But it’s an idea.

[laughter]

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Hello. You mentioned that you’re a cultural determinist. So looking at, for example, North and South Korea, or 20, 30 years ago, Hong Kong, China, it seems to me that there is a difference, combined with the fact that there is this, what’s called the deep roots literature in economics, which basically looks at how long has there been a state in this country?

From a cultural conservative perspective, that would be fairly pessimistic, looking at economic development in places that do not have a long history of statehood. I was wondering if you could discuss that a little bit. Then, to what extent it might be possible to sort of create sustainable, formal institutions in these places that do not have a long history of them, a la Paul Romer’s charter cities.

BROOKS: Yeah. Well, I’ve tried to be a cultural determinist, but not a total nut about it. So I wouldn’t want to deny the importance of institutions and economic laws and conditions. Obviously the difference between North and South Korea is probably not primarily culture. It’s probably institutional.

I think we’ve learned this at great national cost. It’s very hard to impose institutions that require high trust onto societies that have low trust. I covered the Soviet Union and the decline of the Soviet Union and the emergence of Russia. We sent teams of economists with privatization plans, and we emphasized the economic institutions they would need to thrive. But we didn’t appreciate the depth of lack of social trust. So I think we sort of got that wrong and did a great disservice.

If you don’t take that — especially levels of social trust — into account, it’s very hard to impose one society’s institutions onto another, which is why I’ve always been a little impatient with “Should we be more like Denmark?” I’m not sure we have that choice.

COWEN: A question from the iPad. “The more we learn about our behavior, the larger a role, culture, peer group, and genes play in determining it. How does this impact or what does this leave for free will and moral agency?”

BROOKS: Well, I do think our genes and our cultures are biasers, but we still make choices. And in part, one of the things we deal with, we have the power . . . Like everybody, you’re going to talk to Danny Kahneman soon, and I’m a believer, like everybody, that 99 percent of our processing is unconscious. But that doesn’t mean you can’t control your life.

You can decide to join the Marine Corps, and then the Marine Corps will influence you in a zillion ways, most of which are unconscious. You can decide to get married, and then that will affect you in unconscious ways. You can decide what environment to put yourself into, and then the environmental influences will be very determinative. But making that decision of how to plant yourself — that to me, strikes me as a free will decision.

And finally, I fall back on the old saw — I forget who said this first — that everything in the philosophical literature makes free will seem impossible, and everything about lived experience makes it seem inevitable.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Thank you. In your first question, you alluded to a kind of a communal mentality in the 1950s, and an argument could be made, I think, that maybe that was born out of the sense of mission from World War II. And I’m wondering if there is hope and if we are optimistic, if something short of war, what kind of crisis . . . or do you foresee something? Or is it an anti-Trump movement that could bring that kind of sense of communal ambition or collectivism and goodwill and love together?

BROOKS: Yeah. If we got invaded by Canada.

[laughter]

Not even all of Canada, just part of Canada, the weaker part.

I do think there are times where cultures have turned around and without war. The two examples that I know most about are Britain between 1830 and 1848 and America, as I mentioned, between 1890 and 1910, say. In both those cases, there was a religious revival first, which made everybody much more communal. Then there was a civic revival, which I described, and then there was a political revival.

It seems to me we’re not going in that order. I think we are genuinely having a civic revival. I don’t see, despite what I said earlier, not really a lot of evidence of a religious revival. A lot of upsurge of institutions and responses. I’m hoping that’ll lead to a political revival down the road.

One of the things that 1950s culture . . . And I’ve got Jonathan Sacks on my mind, but I think he has a good metaphor. The problem with that 1950s culture was that — he calls it a guest house culture. The Protestant establishment owned the country, and everybody else was just guests in it. And if you behaved according to the cult of the laws of the Protestant establishment, they would let you in. But there wasn’t really ownership, and that became . . .

The reason there were so many tight communities in Chicago, say, in African American neighborhoods, Italian neighborhoods, Polish neighborhoods is because those people did not have access to Michigan Avenue. The community was in part caused by lack of opportunity. Sacks says we smashed that up for good reason because we didn’t want to live in somebody else’s house.

But then we went to what he calls the hotel culture, where we’ve all got a private room. We don’t really invest in the building; we don’t really know our neighbors. And we’re seeing the aftereffects of that, too. I have tremendous faith in humans’ ability to solve their problems. So I assume we’ll find a way to create a much more communal organization, but we’re not going to go back to the 1950s.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: But it would be an Airbnb culture then? Can I take that metaphor that far on the way?

[laughter]

That gives me hope.

BROOKS: Yeah, it bothers me that a lot . . . [laughs] It doesn’t bother me, but a lot of the really big social technologies are designed to make human relationships friction free and temporary: Airbnb, Tinder, even Facebook to some degree.

There has to be some other way to solve the problem for long attention span. And the one thing I’d love to do is demote how we think about high tech and especially social media. I think our smartphones do a lot of great stuff for me. I can find my way anywhere in the world now because of my smartphone. So that’s a great tool, but I don’t expect it to lead to a new consciousness or solve my emotional problems.

My car is a great tool, the wheel is a great tool, electricity a great tool I don’t expect to spiritually deliver the society. But somehow we got in the business of expecting tech to deliver a new consciousness and a new social order. That’s just asking too much of a tool. And so I doubt it’s going to come through some technology.

My car is a great tool, the wheel is a great tool, electricity a great tool — but I don’t expect them spiritually deliver the society. But somehow we got in the business of expecting tech to deliver a new consciousness and a new social order. That’s just asking too much of a tool.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Yeah, hi. I have a question about foreign policy, which is a subject you write quite a lot about in your columns. Earlier in this conversation, you mentioned that you share with Edmund Burke epistemological modesty.

I’m wondering how you square that with being a Reaganite. It seems to me that in order to run a successful foreign policy of the sort that America wants to run that you have to know quite a lot about the world, and how can you know enough?

BROOKS: Well, I think, I would say Reaganite, and then I’ll get to Iraq in a second. I think the secret of Reaganism was understanding that planned economies were probably going to be doomed. And he understood that better than most other people, probably for the right epistemological reasons. He wouldn’t have used the word, probably, but having that confidence that planning was going to fail was a right intuition.

Also having an ability to think in moral terms. To me, Communism — he said evil empire — to me, Communism really was an evil system that led to untold human misery. So basing one’s intuitions on those things seems to me the right thing to do. Now the question then becomes, how much can you remake the rest of humanity? And Reagan was pretty careful about how he committed troops and tried to remake other nations. George W. Bush was less careful.

And I remember I wrote a column in the run-up to the Iraq War, which I supported, how would Michael Oakeshott think about this problem? And Oakeshott is sort of Burke-ian, though he denied it, but same sort of cultural style. Oakeshott would be like, “You’re going to screw this up. You do not understand that culture.”

I wrote 700 words on why Michael Oakeshott would really oppose the Iraq War, and that any conservative should, and then, unfortunately, I wrote another 150 on why Oakeshott was wrong, and if I could take back that 150, I probably would.

But there’s a balance between . . . You can’t be paralyzed by your modesty in world affairs. You have to act. And to me, to not try to plan too much but just sort of be a gentle force for democracy and human rights, that strikes me as the right posture, just constantly pushing for these things, and then hoping something good happens. You can’t tell what effects you’re going to have, but if you push for the right things that are your values and you have faith in them, then that strikes me as the right posture.

We’ve had two presidencies in a row who didn’t do that. Obama, it was interesting. Obama never saw a problem he didn’t want to transcend, except on foreign policy. He always thought you messed up by doing too much, not by doing too little. That was his bias. Never do too much. And as a result, I think he did too little.

Then Donald Trump doesn’t seem to believe in democracy promotion at all. He has a more law-of-the-jungle mentality about foreign policy. So I still stick to Reaganism, that basic leaning toward democracy and dignity and progress.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Thanks so much for sharing your thoughts with us. I want to go back to your understandings and learnings from the Trump voter. It’s fascinating, the age spectrum that it crosses. My 26-year-old son oftentimes looks at a younger Trump voter and says, “Where did they get harmed by some of the past?”

And I’m just curious, what is your sense about how do we move forward so that this Trump voter is better understood, is indeed heard, if that’s indeed what’s being sought after, and that the tangible results can be seen and felt and ultimately changed, the dynamic here that’s created such dysfunction?

BROOKS: Yeah, well, I happen to know a lot of Trump voters of the 18-to-24 age group, and some of it is sort of rebellion against liberal professors, but a lot of it is a pretty thought-through view of what constitutes community. And I’ve had it argued to me many times that my view of community, which is about pluralism and cosmopolitanism, is attenuated and unrealistic.

And that they generally do argue, and I’ve had it said many times to me, that “You just can’t think there’s such thing as diversity and community at the same time, that these two sit in much greater tension than you’re willing to acknowledge. I’m willing to face the reality that diverse societies tend to be attenuated societies with low social trust. I’m willing to adopt the policies that are consistent with that, and you’re not.”

I disagree with that argument, but it’s not an argument without merit. So the young voters I’ve interviewed or have known personally, they’ve got some philosophical background to what they’re thinking.

COWEN: From the iPad, “What idea or cultural inspiration will be the motivating force for the next generation in China?”

BROOKS: I’ve been to China twice or three times, so I don’t know.

[laughter]