In this crossover episode with EconTalk, Tyler joins Russ Roberts for an in-depth exploration of Vasily Grossman’s Life and Fate, a monumental novel often described as the 20th-century answer to Tolstoy’s War and Peace.

Russ and Tyler cover Grossman’s life and the historical context of Life and Fate, its themes of war, totalitarianism, freedom, and fate, the novel’s polyphonic structure and large cast of characters, the parallels between fascism and communism, the idea of “senseless kindness” as a counter to systemic evil, the symbolic importance of motherhood, the psychology of confession and loyalty under totalitarian systems, Grossman’s literary influences including Chekhov, Tolstoy, Dante, and Stendhal, individual resilience and moral compromises, the survival of the novel despite Soviet censorship, artificial intelligence and the dehumanization of systems, the portrayal of scientific discovery and its moral dilemmas, the ethical and emotional tensions in the novel, the anti-fanatical tone and universal humanism of the book, Grossman’s personal life and connections to its themes, and the novel’s enduring relevance and complexity.

Watch the full conversation

Recorded November 4th, 2024

Read the full transcript

Thank you to listener Roger Barris for sponsoring this transcript.

RUSS ROBERTS: Today is November 4, 2024, and my guest is economist, author, podcaster, and blogger Tyler Cowen of George Mason University. This is Tyler’s 19th appearance on EconTalk. He was last here in November of 2023, discussing who is the greatest economist of all time.

Our topic for today is Vasily Grossman’s masterpiece, Life and Fate. We will minimize spoilers, but I’d encourage you to read the book before listening, if that’s your habit. As I’ve suggested, you may want to read this on the Kindle, which makes it a little easier to follow the characters because it’s easy to search for them if you forget who they are.

This episode is also available on Tyler’s podcast, Conversations with Tyler. Tyler, welcome back to EconTalk.

TYLER COWEN: Thank you, Russ. Is it a spoiler to tell them who won the war in the Battle of Stalingrad?

ROBERTS: I was thinking of that. I think we can reveal that.

COWEN: Okay, that’s fine. Let’s start then. You have some introduction.

ROBERTS: Well, I wanted to just say a little bit about Grossman and the book very briefly. Vasily Grossman was born in 1905 in Berdychiv. Berdychiv, at the time, was part of the Russian Empire. It eventually, in 1922, after the revolution, became part of the Soviet Union. He rose to some fame as a war correspondent. He covered the Battle of Stalingrad.

People, when they talk about this book, Life and Fate, say it’s about the Battle of Stalingrad. No, it’s not. It takes place around the time of the Battle of Stalingrad. There is some war in the book, but that is, I think, a very misleading summary of what the book’s about.

He wrote the book after World War II. The book was arrested by the KGB in 1961. They came to his house. They took the manuscript. They took all the typewriter ribbons. Those of you who are older than a certain age will know what that is. They tried to find other copies. They ended up digging up the garden of a friend of Grossman’s but did not find any other copies. He was successful in hiding a couple of copies with friends. Eventually, the book was smuggled out in 1980 and published in Switzerland, published in the Soviet Union in 1988. Grossman died in 1964, unaware that his book had survived.

Just one other biographical note, which is relevant because of the nature of the book. His mother was killed in 1941 when the Nazis overran Berdychiv. Berdychiv was a town of a little over 50,000 people. About 40,000 were Jews. It had 80 synagogues, and his mother died in the murders there. His mother is an important part of this book in a fictionalized role, and we’ll talk about that.

Tyler, give us your short initial assessment of this book.

COWEN: Amongst Soviet authors, he is the GOAT, one could say, to refer to our earlier episode. But this, to me, is one of the very few truly universal novels. The title itself, Life and Fate — it is about life and fate, but the novel is about so much more. It’s about war. It’s about slavery. It’s about love, motherhood, fatherhood, childbirth, rape, friendship, science, politics. How many novels, if any, can you think of that have all of those worlds in them in an interesting and insightful manner? Very few.

The one that comes closest to it is, in fact, his model. That’s Tolstoy’s War and Peace, a three-word title with an and in the middle and two important concepts. They’re both about war. They’re both about the invasions of Russia or the USSR. There’s a central family in both stories. The notion of what is fate or destiny is highly important to Tolstoy, as it is to Grossman, though they have different points of view.

Napoleon plays a significant role in War and Peace. In Life and Fate, Hitler and Stalin make actual appearances in the novel, which I find shocking when I read it, like, here they are on the page, and it’s actually somewhat plausible. So, he’s modeling this, I think, after War and Peace. He actually pulls it off, which is a miracle. I think it is a novel comparable in quality and scope and import to Tolstoy’s War and Peace, which is sometimes called the greatest novel ever. So that is a pretty amazing achievement.

ROBERTS: Yes, I think I mentioned on the air in an earlier episode — when I was reading it, I enjoyed the first 100 pages. After 200, it got a little better. Somewhere around 300 or 400, I couldn’t put it down. There are so many passages that move you to tears or to incredible emotional reaction. It’s not a traditional novel akin to War and Peace or akin to other Russian novels such as The Brothers Karamazov or In the First Circle, which we talked about here on the program. Previously, it is what our guest, talking about In the First Circle, Kevin McKenna, called polyphonic. Here’s how he described it.

He said, “Dostoevsky and Solzhenitsyn are so similar. Dostoevsky is famous for what is called the polyphonic structure of his novels. That is, rather than having — as we are used to in the West — one central, main character who stands as the centerpiece of everything that happens in the novel, the polyphonic structure of a Dostoevsky or Solzhenitsyn is that there is not a main central character. There is a cast, I would say perhaps five to eight central characters, as well as perhaps three to four central, major themes, so everything is kind of a fugue of characters, a fugue of plot.”

In the case of Grossman and Life and Fate, I would say there are eight to ten main characters. There are about 100 characters overall, and that can be discouraging when you start the book. But if you keep reading, you’ll realize that only the eight to ten who are the main ones are going to reappear over and over again and, often, dozens or hundreds of pages apart when they reappear.

But as you point out, Tyler, there are so many interesting intellectual and emotional themes of the book. It really spans an enormous part of the human experience. In that sense, you could argue it’s the greatest novel of the 20th century and, for me, one of the greatest novels of all time. Certainly, one of the greatest I’ve ever read.

COWEN: I think another influence — and Grossman himself cites him repeatedly — is Chekhov. The chapters in Grossman often are mirroring Chekhov short stories, but they’re woven together in a way that Chekhov short stories are not. But the notion of “How is it you tell a narrative during a war that is so big and important and tragic?” I take to be one of his central endeavors, and that, too, is something he mostly pulls off.

ROBERTS: Yes, the Chekhov part — there are just so many numerous, unforgettable vignettes of characters struggling with betrayal, struggling with the state bearing down on them, whether it’s the Nazis or the Communists. One of the themes you didn’t mention that reverberates throughout the book is the parallels between the Nazis and the Communists. They’re both, in many ways, fascist, authoritarian states, but what he’s really interested in is how they grind the individual down and how the individual stands athwart that grinding, stands and says, “Stop. No, I’m a human being.”

I found that when I thought about the title, you’d think, “Well, why isn’t it called Life and Death or Freedom and Fate?” For Grossman, life is really about freedom, so in a certain sense, the title Life and Fate, for me, is very much not the only, but one of the central themes of the book, which is, how human beings caught in the throes and the gears of the state manage to maintain their freedom and their essential humanity despite that brutal, brutal reality.

COWEN: This is where I think we might disagree because I disagree with everything else I’ve read about this book, including the main Grossman biography. If I had to name a central theme of the book, I think it’s, in a funny way, a patriotic book, arguing that Communism, for all of its horrible faults, is actually better than fascism and explaining or showing to us why it is better than fascism. I have a riff on that, which I’ll do, but let me just put that out on the table and hear your immediate reaction.

ROBERTS: I’m not sure I disagree with that. I wasn’t suggesting that they were equivalent. It’s just that they have certain powerful equivalencies that the characters in the book find repellent. The idea to the Communists that they have a brother in the Nazis, the idea that to the Nazis, they have a brother in the Communists is extremely disturbing. Grossman forces a number of his characters to confront those similarities.

But I agree it’s a very patriotic book. It’s a very Russian book. There’s a lot of talk in his biography and in people who write about him, how much he was pro-regime, how much his antagonism to the regime and the Soviet regime changed, how it grew over time, and like his characters, and it’s a very autobiographical book, which is bizarre, but it’s a very autobiographical book.

The main character, Viktor Shtrum, is a physicist, a world-class physicist. Grossman himself was a chemist, not a world-class chemist as far as I know, but he identified with Shtrum’s marital problems, his problems of keeping faith with his conscience. In that sense, I think he’s overwhelmingly, certainly, on the side of the Russians, but I don’t think he has any romance about Communism.

COWEN: I think what he sees as the fundamental difference is that for him, fascism is ultimately just a philosophy of death. He says on page 94, “Man and fascism cannot coexist.” The feature about Communism — and he’s under no illusions about its evils, as you just said — is there’s some degree of negotiability built into the system.

If you look, say, when the Nazi commander, Liss, is interrogating Mostovskoy, Liss just keeps on asking questions. There’s no dialogue. Nothing can happen. There are no real questions, there are no real answers, and Mostovskoy simply ends up being killed. The other characters going to the camps — they’re simply killed. There is no negotiation.

But if you look at the main Soviet interrogation scene, when Katsenelenbogen is interrogating Krymov, a scene which goes on for quite a while, they talk back and forth. It’s weird. It’s sick. It’s twisted. There’s torture involved. But actually, Krymov comes away from that scene alive. He at least learns something. Also, you have figures–one of them is Viktor; another is Novikov, the tank commander — maybe they’re imperfect, but they’re not just all bad, by any means.

ROBERTS: Oh, for sure.

COWEN: They’re virtuous in significant ways. Fascism in this novel cannot create that. Even the nonbelievers in fascism, what’s the fellow’s name?

ROBERTS: Ikonnikov?

COWEN: No, no, no. He’s a German. He doesn’t really believe in Nazism, but he ends up going around raping Russian women. That’s the fascist version of someone who’s not a believer, not nearly as good as the Soviet version.

I think he knows he rooted for the USSR to win the war. In part, in this novel, he’s trying to explain to himself, “How could you root for such a horrible society, and how could it have been on the side of the Allies?” Which, of course, we would have been rooting for at the time. That, I think, is part of his answer, the central idea of negotiability, that it never quite goes away under Communism. Even Viktor is saved by this weird intervention from Stalin, which makes no sense, but there’s some outcome possible other than just death and destruction.

ROBERTS: Yes. I want to come back to the torture theme, the scenes in the Lubyanka with Krymov. I’ve read a lot of Solzhenitsyn. I’ve read all The Gulag Archipelago. I’ve read many of his novels. I’ve read about a lot of scenes in Lubyanka. I can’t say I feel like I’ve been there, but it’s familiar to me. It’s the prison where people were tormented, not merely tortured but tortured until they confessed, often, sometimes tortured until they confessed things that weren’t true, sometimes tortured until they confessed about loved ones or comrades or colleagues. It’s an unbearable, tragic place.

Having read all that before, I felt, reading Grossman’s account, an awareness of how hard it was to stay on your principles. It’s almost, yes, they tortured their victims, and they extracted confessions under torture. But by the end, you feel like Grossman captured this idea that for many of them, they were glad to confess, even though they knew what they confessed to wasn’t true, but they did it out of love for the system.

All the purge, the show trials of the ’30s, which, in 1938 and ’37, keep coming back into this book, and the purges before that, where Stalin’s opponents were systematically killed, none of them were killed at night by the firing squad or with a murderer. They all confessed. What Grossman captures, which I’ve never really read with this level of intensity, the willingness of people to confess, even though they know it’s not true — what they’re confessing to — because they think the system itself is worth preserving. They have a . . .

I would make a distinction. It’s a Dostoevskian distinction between the church and its practitioners, right? It reminds me of the grand inquisitor scene. The officers of the church — and here I’m talking about not any particular church but any religious dogma — they’re flawed. They’ve lost the original doctrine that inspired the believers, but the idea of giving up that doctrine is so painful to the adherents that they confess to things they didn’t do because they have to believe that the system, the church, still stands. In this case, a secular church, the church of Communism. Do you feel that?

COWEN: It’s a profound book on the psychology of confession. I think another element of how people come to confess is that in part, they believe they are guilty. They may not believe they’re fully guilty. If you think of Krymov, if you reread the earlier parts of the book, he does, in fact, whine about his colleagues in such a minor way, but that looms larger and larger in his mind as they talk to him.

He starts wondering, “Well, have I, in fact, done something against the system?” when confronted with the power of the interrogator. And, of course, the indirect reference to Dostoevsky and how the system, ex ante, takes advantage of what a Christian might call original sin, to put people in positions where they almost cannot help but confess because they believed something, to begin with.

Then the theme that passivity underlies how so many social structures operate, the novel is quite profound on, including how the camps operate, how an army battalion operates, how chains of command operate in the military — that the default of passivity is responsible for so much of social order, even when that social order can be very, very bad.

By the way, it’s Lieutenant Peter Bach who is the German I was referring to in my earlier comment.

ROBERTS: I should just mention, as you’ve already alluded to, there are many historically real characters in the book, mixed in with the fictional ones, and the list of characters distinguishes those.

There’s another parallel between the Soviet and the Nazi systems that I found just fascinating. Each side has its own hall monitors in the middle of a war. You’re fighting a war. It’s life or death. And yet there’s a commissar, meaning an operative of the Communist Party on the Russian side, Soviet side, and on the German side, you’ve got the SS, and they’re both looking to uncover a sense of errors in dogma. They’re looking for heresy.

Whether it’s negative remarks about Stalin or Hitler or it’s something nice about the Jews, they’re all looking for things to crack down on. It’s such a handicap in a war. Novikov, of course, has incredible moments of this. The idea that you would hamper your war effort with ideological purity questions and that both sides did, at least in Grossman’s version, was really eye-opening for me.

COWEN: Yes, absolutely. One thing I found striking in the book is just how many literary references there are, and they all seem relevant. One thing I did when reading through, I tried to note what was mentioned twice. Tolstoy is mentioned more than once. There’s this Chekhov short story called “The Bishop.” It’s not only mentioned twice, but we’re told, “You must go away and read ‘The Bishop.’” Of course, I went away and read “The Bishop.”

“The Bishop” is about dying. It’s about what is transient in life. It’s about the fragility of a social reputation. It’s about a mother-child bond. And when the bishop, who was well known in his lifetime, dies, people were not sure he had ever been there. But the one person he had been real to was his mother, and that was more important than his social role as a bishop.

That’s the Chekhov story that he takes greatest care to point us to, and I think so much of the novel is about motherhood. It’s Vera giving birth that is heralding the turn of the tide with the Battle of Stalingrad itself. It’s when life is again possible that the Soviets start to win.

ROBERTS: It’s a great insight. Viktor, the main character, sort of, one of the main characters in the book, receives a letter from his mother on her way to her death in a Nazi death camp. It’s quite powerful. It goes on for, I don’t know, 10 pages or so.

COWEN: One of the best parts of the book, maybe the most moving, yes.

ROBERTS: Grossman writes this, really imagining what his own mother would’ve written had she been able to write to him before her death in the murders of Berdychiv in 1941 that I mentioned earlier. This is just stunning. Grossman wrote two letters to his mother, his actual mother, after her death. One he wrote nine years after his mother died, and one he wrote 20 years after his mother died, right before his own death, and we have those letters.

They’re in the back of a collection of Grossman’s we’re going to talk about in a future episode, called The Road, and they’re deeply moving. He believed and said — I think in the letters — that his mother would be eternal because of Life and Fate, which makes it even more poignant that at the time of his death, he didn’t know that the book would survive. But clearly motherhood is a major theme of the book. Sofya’s scene — the doctor in the death camp — is also overwhelming. He clearly was fascinated by maternal love.

COWEN: What do you make of the fact that the very final chapter is characters who have no names whatsoever? That reminds me a bit of the Chekhov story. I took that to be, well, in some longer run, none of the particular identities of these individuals will be remembered, that simply the life and fate of humanity goes on, and its people, in essence, without names.

ROBERTS: That’s beautiful. I didn’t have any thoughts on that, other than that I was expecting something more dramatic. I like how you’ve made that different. I wondered whether he’d had a chance to really edit the final version before it was confiscated, but I like your ending better.

COWEN: I think it’s deliberately not dramatic. It’s as far from drama as you can get, in a way.

ROBERTS: Yes, that’s nice.

COWEN: Stendhal is also mentioned several times, The Charterhouse of Parma, which is a book about war and individual fate, and I strongly suspect all of the literary references have some meaning to Grossman. There’s Dante and Swift and Homer and Huck Finn, which are all about journeys, and he’s taking us on our journey through this war, through this battle, through Soviet and Nazi life. I think that’s another way he thought of the book.

ROBERTS: That’s right.

COWEN: Dante, with the rungs of hell — obviously, we’re seeing the 20th-century version of the rungs of hell, and so on.

ROBERTS: Yes. It’s really a nice way to put it. There’s no clean narrative thread, and it captures the chaos of war that way. The characters who move away come back. They’re often homeless. They’re thrown out of their own houses. They’re forced to take in a boarder who’s richer than they are, more connected than they are, and they’re pushed into a smaller room in the back. They leave their family and yearn to come back.

There is this constant theme of journey and home, and everyone in the book is unsettled, [laughs] not just by the war. Their own emotional journey is troubled. Viktor’s marriage — as Grossman’s marriage was — is deeply complicated. There’s a lot of betrayal in the book as well, and at the same time, there’s a lot of kindness.

You say, “maybe the most powerful passage of the book.” There are so many. One of my favorite passages — I’m not going to read it, I don’t want to spoil it, but it’s about an act of senseless kindness, an act of kindness that a Russian woman does for a German soldier. She actually says out loud to her friends that she can’t explain it. This idea of senseless kindness standing in the universe up against evil — it says that explicitly.

Let me see if I can find this passage. Hang on. Here it is. He says, “The private kindness of one individual towards another, a petty, thoughtless kindness, an unwitnessed kindness, something we would call senseless kindness, a kindness outside any system of social or religious good, but if we think about it, we realize that this private, senseless, incidental kindness is, in fact, eternal. It is extended to everything living, even to a mouse, even to a bent branch that a man straightens as he walks by.”

That’s another theme of the book. Even when we might weight evil in its magnitude, dwarfing these small acts, he takes them and he elevates them. He makes them shine for us so that, in his view, they’re the whole thing.

COWEN: Tanner Greer said on Twitter that he thinks kindness is the central theme of the novel.

There’s also a part on page 283 where Grossman gives what I think is his intellectual, ideological solution to the whole mess, and of course, he cites Chekhov. Let me just read a short part here. “Chekhov is the bearer of the greatest banner that has been raised in the thousand years of Russian history, the banner of a true, humane, Russian democracy, of Russian freedom, of the dignity of the Russian man. Our Russian humanism has always been cruel, intolerant, sectarian.”

And he talks about the partisans, the fanatics, and he thinks Tolstoy is also an intolerant fanatic. But Chekhov says, “Let’s put God and all these grand, progressive ideas to one side. Let’s begin with man. Let’s be kind and attentive to the individual man.” That, I think, is his bottom line, and that, too, comes from Chekhov. Then he cites Chekhov’s book about prison camp, Sakhalin Island, which is also a fantastic story.

ROBERTS: What other themes did you want to mention that we haven’t talked about?

COWEN: The notion of what people will put up with and how they deal with it, of how they will keep on absorbing indignities. And the set point — you could say it gets reset, and then something else happens and something else happens. And he’s so psychologically astute in presenting that in a wide variety of settings for different people, whether it’s interrogation, torture, being in the camp, seeing your child suffer.

It’s one of the hardest things about this novel to read. There are so many instances of it, and any one of them is heartbreaking, and you keep on seeing it again and again. I take it you found that hard as well.

ROBERTS: Well, it’s funny when you just . . . I think anyone listening to what we’ve said so far would say, “Boy, this is a depressing book.” Right? It’s about death and war, death under the Nazis, death under the Communists.

I did not find it depressing. I did not find it a dark read. Let me expand on that a little bit, and I want your reaction. Yes, people go through horrible things, but one of the themes of the book is the resilience of the human spirit, and he talks about it explicitly in a few places. He talks about the desire to live even when you think it’s “hopeless.” He talks about how people do things that are not going to have an impact for months and maybe years, even though they think they’re about to die, but they do them anyway.

The human circus or whatever you want to call it, the parade goes on. It’s weird to say this. I didn’t find it a particularly dark book. I was not depressed or down. I found it a nice example of what I talked about with Susan Cain. I found it a very bittersweet book because there’s a lot of life in it. Do you agree with that?

COWEN: I don’t find many things depressing. It is tough to read. I think most ordinary readers — if you just polled them, they would say, “This is depressing.” But that the book itself exists is part of the ultimate reason why it’s not depressing, that the book managed to survive. That’s a testament to some of the negotiable elements in the Soviet system. Even though they tried to destroy it, you have to wonder, how hard did they try? When you read the stories of how it survived, it seems maybe they could have destroyed it if they had truly wanted to.

One thing I’m struck by — the terror reign of Stalin more generally — for all the terrible things he did, he had some modest tendency to protect his geniuses, whether it was Pasternak or Prokofiev or Shostakovich or Grossman. Those are not the people he killed. Babel was killed, but the geniuses tend to survive, and they’re able to do something, however twisted it may have been, or whatever circuitous path it had to go through to come out and be shown to the public. Maybe Shostakovich is the clearest example of that.

ROBERTS: It’s really interesting. Obviously, he was ruthless with respect to his political rivals, including people who —

COWEN: And just kulaks, right?

ROBERTS: Yes. His best friends.

COWEN: He killed many millions of kulaks.

ROBERTS: Yes. No, I’m talking about his colleagues from the early days of the revolution. He brutally killed them, and as I said earlier, he killed them after having them confess first, which I don’t know if that was gilding the lily or not for him, or if that added to the delight that he found in that. I don’t know if he protected his geniuses. He certainly didn’t generally let them thrive. He forced them to conform to his own movement standards.

COWEN: There’s a page. We mentioned it when we agreed to do this. It’s page 217, on artificial intelligence. What did you make of that?

ROBERTS: [laughs] Oh, I loved it. I don’t agree with every word of it. I don’t know if prescient is the right word, but it was eerie. It was one of the two most intellectually interesting things in the book for me, as opposed to literary, emotional power. We’ll come back to the second in a second. You want to read that passage? It’s a great passage. It’s a whole chapter. It’s only a couple of paragraphs.

COWEN: I’ll read part of it. “An electronic machine may carry out mathematical calculations, remember historical facts, play chess, and translate books from one language to another. It is able to solve mathematical problems more quickly than man, and its memory is faultless. Is there any limit to progress, to its ability to create machines in the image and likeness of man? It seems that the answer is no.” There’s more, but that’s just the opening part.

There was, of course, throughout the 1960s, a Soviet obsession with artificial intelligence. We often forget in the West, but they, as a regime, were convinced it was going to be the future. It pops up a great deal in Soviet science fiction. There’s that book about the science city in Siberia that was created by the Soviets. There’s a whole chapter in that book about what they were trying to do with AI. It was one of their top priorities.

Obviously, they didn’t get very far, but Grossman is showing he was swept up in that mania. I think what he says on this page is true, except for the memory being faultless. We know that’s not true. There are still hallucinations.

ROBERTS: Yes — well, today. We’ll get there, maybe.

COWEN: Today.

ROBERTS: He wrote that in probably the late 1950s, sometime in the 1950s. You talk about the Soviet interest in AI. There wasn’t much I in AI in those early days. He was fascinated, clearly. That page doesn’t really change much of the book, [laughs] if at all. He just threw that in there because he was interested in it, but it gets at —

COWEN: Well, I don’t think it’s thrown. It’s not thrown in there. It’s there for a reason.

ROBERTS: Yes, tell me.

COWEN: Let’s talk about that reason.

ROBERTS: Tell me.

COWEN: Well, look, the very last sentence on that page, which is its own paragraph: “Fascism annihilated tens of millions of people.” Before that, he’s mentioning that the AI machine would be so large — he didn’t know Moore’s law — that it might take up the entire surface of Earth. There may not be room for humans on Earth, I think is what he’s saying. I think he’s worried about artificial intelligence, and he views it as potentially the new fascism. That’s how I took the section.

ROBERTS: No, I think that’s fair. I think that’s fair.

COWEN: He’s saying fascism doesn’t go away. It comes back in many forms. There are always forces that could enslave or destroy mankind, and he worried — I’m speculating here — about his own regime’s embrace of the AI program. So, he’s like an early Eliezer.

ROBERTS: [laughs] Or a worrier about technology. I think his worries about the analogy he’s making there between fascism and technology, that they enslave us — I don’t think they enslave us the way our phones enslave us, but they have the potential to be a system. I think of the man of system, the Adam Smith quote from The Theory of Moral Sentiments, this idea that if you have a view of the world that you want to impose on the chessboard of the human experience, you’re going to do some bad things. I take it to be in that spirit.

COWEN: Note also the middle paragraph, where he’s talking about humans. He cites, first, childhood memories, and a bit later on, a mother’s tenderness, thoughts of death. The main themes of the novel are being echoed by this interlude, where he is contrasting humans to the machine. The machine, for him, eventually becomes all-powerful. It becomes a kind of god and can create humans in its image that are in a way superior, and I think he’s terrified by this.

ROBERTS: Yes. Just like I am a little bit. Fair enough. I didn’t mean to suggest it didn’t belong at all. It’s just a wonderful little interlude. I think I was overwhelmed by the fact that it seems like most of it could have been written yesterday.

ROBERTS: The other part that I just was fascinated by was his comparison of fascism to quantum mechanics and the cutting edge of physics. What were your thoughts on that analogy and how . . . Forgetting this particular example — I want your thoughts on that — but this idea that scientific metaphor and scientific narrative and the way we see our role in the universe doesn’t just affect the progress of science. It comes into our culture in all kinds of ways. That’s a very provocative idea.

COWEN: I think it’s the same theme. I read him as basically a humanist, like Chekhov, fairly skeptical about science. Viktor, yes, you could say he’s the hero or, certainly, center of the novel, but what ends up happening is, Viktor — this is not too much of a spoiler because we know what did happen — ends up helping Stalin build nuclear weapons, and he can’t be too thrilled by that.

He may see a positive side that the motherland could be defended against future fascists, but I think he has strongly mixed feelings about that. Viktor is co-opted by something that Grossman himself does not quite believe in, and the scientific mentality is part of the problem. The way science operates in the novel and in this society — there’s more betrayal in science than anywhere else. You’re highly at risk in science. I don’t think he feels that’s entirely accidental to science or fully the fault of Communism.

ROBERTS: Viktor’s character deals relentlessly and painfully with the ethical dilemmas of being a favored citizen of the state, very similar to In the First Circle, where the characters — they’re in a gulag, but it’s a privileged gulag because they’re doing research that benefits the state, which puts them, as the prisoners, in a very unpleasant ethical situation, which is really the essence of that book.

In this case, another thing that Grossman captures, I thought, with such accuracy and lets you feel it, is the exhilaration of scientific discovery. Viktor makes a discovery. The exact nature of it isn’t described, but he’s clearly on the cutting edge. And as you say, it may lead to many things, but it’s mainly a theoretical discovery. And there’s an ego part to it, but most of it’s just, he’s just pushed out the frontiers of human knowledge, and it’s an incredible part of the human experience. He’s so alive after that, and his mood so oscillates with his ability to do that or not do it, depending on whether he’s in a favored status with respect to the regime.

I think that’s just so much more part of his psychological trials and tribulations, the ability to have that freedom or lose it clashing with the pressure the regime puts him under to serve its own purposes. That, to me, is an enormous part of his character’s dilemma.

COWEN: Grossman’s also writing at a time where many, many intelligent people think science perhaps is about to end the world. There’s that possibly apocryphal story that some of the people at the RAND Corporation, the decision theorists — not all of them put money into their retirement accounts because they thought it wouldn’t be necessary. A nuclear war would come. It was an extremely common view amongst the elite. I think he held a Soviet version of that.

That pops up in the novel, that yes, you’re rooting for Victor, but there’s something about the logic of what went wrong that can so easily end up being recreated, but at a more destructive level. That’s in the background of this novel. I think it’s another reason why maybe I find it a bit less — heartwarming isn’t the word — but a bit less inspirational than one could otherwise make it out to be.

ROBERTS: Fair enough.

COWEN: We can’t get rid of science. Grossman himself is never quite reassured about science, and that one page about AI is put in there to tell us that.

ROBERTS: That’s nice. I agree with that. That’s very nice, Tyler.

He’s got an essay in The Road, which we may talk about in a future episode, where he looks at a painting of Raphael’s called Sistine Madonna. In the Sistine Madonna, Mary is holding the baby Jesus and pushing him forward. It’s a very Grossman painting because it’s about a mother’s love for her child and her willingness to put the child in harm’s way.

There’s a lot more to say about that, but in that essay, Grossman talks explicitly about the hydrogen bomb. This essay was written in 1955, which is about the time, I think, he was writing some of this book. You’re 100 percent right that the potential for human beings to be extinct and destroy themselves is very much in his consciousness.

COWEN: One thing I’ve been thinking about is the question, to what extent is this a Soviet novel, Jewish novel, Ukrainian novel, or Russian novel? Often, it’s thought of as a Russian novel. I’m not sure how much it is because he’s clearly not ethnic Russian. How does the patriotic side of this differ from how a Russian writer would have presented the same? I’ve been pondering. I don’t have a clear answer, but that’s another undercurrent in the book, that it’s very subtly not entirely Russian per se.

ROBERTS: His Jewishness was not always front and center in his mind. He was forced to confront it as the Holocaust arrived, and eventually, as Stalin accused Jewish doctors of trying to kill him. There’s a strong antisemitic thread in Soviet and Russian life. It’s not a Jewish novel, I don’t think. I wouldn’t call it that, but it is written by a Jewish Ukrainian living in a Soviet state with a Russian culture. In a certain sense, I think it’s the ultimate Russian novel. It’s polyphonic. It’s about life and fate. There are really few things more Russian than that.

Yet at the same time, he writes as a Jew. The Jewish parts of the book are not that many, but he gives you a flavor of what it’s like to live in a place where antisemitism can be openly espoused, and it’s painful for some of the characters. They try to hide their Jewishness at times. Of course, we have the Shoah, the Nazi, the Holocaust going on at the same time. An editor might have said to him, “The book’s got a lot in it already. Do you need to put that in?” But he did. He did need to put that in. So, that’s a good question, Tyler.

COWEN: It strikes me as more Jewish than you’re making it out to be.

ROBERTS: Why?

COWEN: Not in the religious sense —

ROBERTS: No.

COWEN: — but the notion of how tragedy is possible and how tragedy can befall you in quite arbitrary ways, or the sudden twists and turns of fate, come very much from the Hebrew Bible, I think. He probably was aware of that.

ROBERTS: Oh, for sure.

COWEN: But he must have been brought up learning it. For me, it’s a highly Jewish novel. Not only, by any means. It’s a universal novel above everything else.

It’s interesting to me. My wife, Natasha, a Jew from the Soviet Union — this and Master and Margarita are her two favorite novels. That she so much relates to this — it tells me something, because she’s uneasy with a lot of what you might call purely Russian fiction, including Tolstoy. Very uneasy with Tolstoy. It’s only one data point, but worth thinking about.

ROBERTS: That’s interesting. I was going to say, when you talked about the twists and turns, that makes it more of a Yiddish novel.

[laughter]

COWEN: Of course, Pale of Settlement.

ROBERTS: It wasn’t written in Yiddish, but there’s a certain . . . I’ll say it a different way to take it a little more seriously. There’s a certain fatalism in Jewish fate, a feeling that we are endlessly the punching bags of the rest of the world, and that is our fate. Obviously, we’re living in a moment where the world’s a little different, with the current situation in Israel. But I think the characters in Life and Fate obviously do feel that they are beleaguered. There’s a certain Yiddish flavor to that that I can’t explain.

COWEN: Also, consider the Book of Job. Who can, himself or herself, actually defend what he or she has done in the eyes of God is another underlying theme in this book. Is it Victor in fact? Not entirely clear, even though he’s the center, mostly a sympathetic character. Who really is doing right under the eyes of God is highly unclear, I think, in Life and Fate.

ROBERTS: Oh, I agree, but we shouldn’t mislead readers. There’s very little God in this book. He doesn’t mention God a lot. God looms over the book to some extent, indirectly, implicitly, but what it means to be a human being and to live a life that is defensible, whether it’s to God or to your friends or to whomever, is a central part of this book.

Grossman himself — again, no spoilers here, but look up Grossman’s entries in Wikipedia or articles that had been written about him. There’s a nice article in 2006 in The New Yorker by Keith Gessen. Grossman himself did some things he was deeply ashamed of. He was ashamed, I think, as far as we know, that he didn’t get his mother out of Berdychiv and that she’d perished there at the hands of the Nazis in 1941. He does sign some things publicly that benefit the regime that he, I think, regrets, and Victor goes through very similar throes of conscience.

COWEN: Let me talk a bit about how I read this book, which was extremely absorbing, highly worthwhile, but it was tough. One thing I did that helped more than anything else was an extensive use of large language models, in particular, the o1 version of GPT. Whenever I would come across a name and not feel I had a full command of what that person had done, I would just ask GPT, “Give me the account of what this person did in the book.”

I did that dozens of times. As you mentioned, many characters. I didn’t catch any hallucinations, actually. It was extremely useful. I don’t think I could have read the book nearly as well as I read it without doing that. Interestingly, there’s one character where it just failed. It delivered for me dozens of times, but when I asked it about Vera, like, “Tell me the story of Vera,” it just gave me back, “Oh, I’m a large language model. I don’t know who Vera is. Check your other sources.” I don’t know why, but other than that, it was flawless and highly useful.

ROBERTS: Well, she doesn’t get a lot of air time, and she isn’t written about a lot. It might have had trouble finding any kind of references to her. As you point out, she plays a very powerful, symbolic role, but she doesn’t take up a lot of pages. I mentioned the essay a minute ago, “The Sistine Madonna.” I asked ChatGPT what it was about, and it totally got it wrong. It said it was about beauty and art. It is not what it is about at all. Claude got it right exactly, which is maybe neither here nor there other than it’s good to have, sometimes, two LLMs to ask questions of.

I found my reading of the book was very inconsistent. I struggled in the early pages, as I’ve mentioned, to get my momentum going. When I read Brothers Karamazov, I read it over a fairly long period of time, but the last 300 or 400 pages I read in a couple days because it’s such a page-turner. This book is not a page-turner. As I said, you might get discouraged, but I found myself more, if I may say so, engrossed in it, engrossed in a Grossman novel.

There’s almost no or very little narrative suspense. We know how the Battle of Stalingrad turns out. The tide turns. I found it interesting that Novikoff, I think, is part of the lead tank group going into Ukraine. He’s very excited to reclaim Ukraine for the Soviets and take it back from the Germans. It was a slightly eerie shadow of the current moment, but I just kept going.

One of my followers on Twitter . . . I apologize to you because this is such a good joke, and we’ll put a link to it in the show notes that don’t have it. But when I said, “We’re reading this book. You should get started. It’s going to air soon,” he wrote back, “I’m on page 12, and all the characters are named Stroganoff. I need more time.” The names are hard.

COWEN: The names are tough.

ROBERTS: The names are hard.

COWEN: Here’s the other thing I did, and this was difficult, but once I finished it, the next day, I started over again at page 1 and reread the whole thing. I’m a big advocate of doing that. I realized I had understood very little of the first 200 or 300 pages the first time I read it. Not that I didn’t understand the words, but I didn’t understand how any of it fit into the story.

I don’t think you can. It’s not a question of if I’d been a better reader or had paid more attention or had been less distracted by the dog. I just think many books — the best thing you do is read them twice directly in a row. As you get to the latter third of the book, actually, probably you could stop it. You don’t have to reread the last third, but certainly the first half, you just have to do it again.

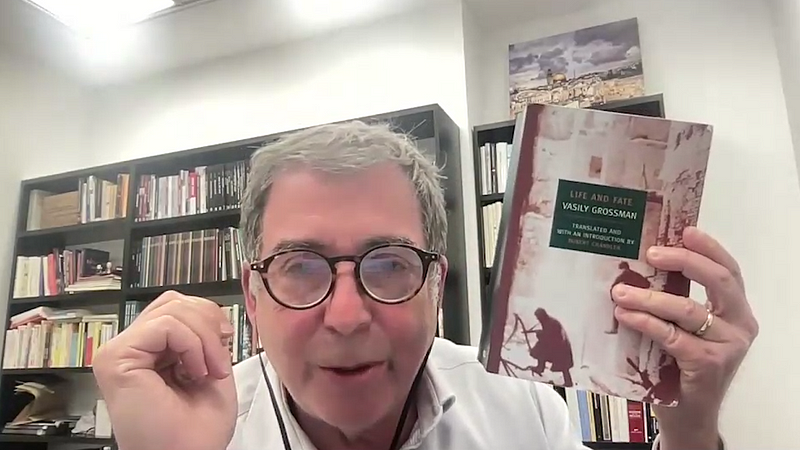

ROBERTS: I read this version. I’m holding this up for YouTubers.

COWEN: Me too. Same.

ROBERTS: Same print, same publisher. It’s New York Review Books Press, who issued a lot of Grossman. It’s about 872 pages. We haven’t actually mentioned that. It’s really long. I should also mention, there’s a prequel which was issued initially under the title For Just Cause, that you can read in English under the title of Stalingrad, which is confusing because Life and Fate, people say, is about Stalingrad. He wrote a book called Stalingrad in English, anyway. It’s also about 900 pages. I may read that next.

It’s funny, when I finished the book, I had the exact same urge. I’m not a re-reader the way you are, Tyler. I thought, “I want to read this again, and I want to do justice to it.” I felt a certain ethical virtue in honoring this man who had written this book and to give it even a second reading, but I felt, well, I should read The Road — this collection of shorter pieces that he wrote — in preparation for our conversation. But I wanted to read it again. I will. I hope I will read it again.

COWEN: The great, great novels from the ’20s — there’s Thomas Mann, there’s Proust through James Joyce from around that time. I think it’s hard to compare this to those, but if you think of the somewhat latter part of the 20th century, this has a claim to be the best novel of a very, very important century. It’s remarkable how few people know it.

I wouldn’t say it’s a page-turner, but I never lost interest, I would say that, not once. I was never thinking, “If I wasn’t doing this podcast with Russ, would I keep on going?” Just was never a question, so in that sense, it was a page-turner for me.

ROBERTS: I want to make sure I say this, Tyler. I’m very grateful you agreed to do this because, I think the quote is from William F. Buckley. I want to say it’s Moby-Dick. I might get it wrong. He read it late in life, and he said it would’ve made him really sad to have died without reading this book. That’s the way I feel about Life and Fate. I feel it would’ve been a loss for me not to have finished it.

I read the book in a very strange way, by the way. I read it both on my phone and on my Kindle app, where I highlighted profusely. Then I read it on Shabbat, on the Jewish Sabbath, when I couldn’t use my Kindle, and I read the paper version. You can see where I bent down page corners. I’m holding this up for YouTube watchers.

I bent down page corners thinking, naively, I would go back and re-highlight those in the Kindle version because they were so good. It’s a compulsion I have. It doesn’t really make sense. I’m glad I read it both ways. They were both helpful.

COWEN: Did you ever get in touch with Robert Chandler, the translator?

ROBERTS: I did.

COWEN: What did you learn?

ROBERTS: He’s scheduled to appear on this program shortly. I want to talk to him about two things. I want to talk to him about The Road, which he edited. He translated it and edited it. I also want to talk to him about the art of translation. Obviously, we’ll talk a little bit about Life and Fate in passing. I’ll put an ad in for The Road. The Road has short stories by Grossman. It has his remarkable essay on Treblinka. It’s about a 40-, 50-page essay on entering Treblinka. He was the first journalist to enter a death camp.

COWEN: That’s a must-read for anyone.

ROBERTS: It’s an incredible, incredible essay. The short stories are really lovely. The short story of “The Road” is from the perspective of a donkey, which is interesting. Tolstoy wrote a wonderful short story called “Pacesetter” that is life from the perspective of a horse. I assume Grossman was riffing on that in some way. This idea that this dumb — meaning mute — creature, that its observations of the human being might be more accurate than our own and give us insight, is really a beautiful idea.

It’s also peppered with lovely pieces from Chandler, with biographical detail. I can’t imagine what it was like to — I’ll ask him — but to translate a book of this size, which, of course, Russian translators are doing this all day long. Constance Garnett and others are translating very large books from a very different language. It must be a fascinating experience. I’m sure it took longer to translate than it took me to read it, so I’ll be interested.

COWEN: I want you to ask him, how funny is the book in Russian? In English, it’s basically not funny, but I hear my wife tell jokes in Russian to her friends all the time. Everyone laughs. I get an English translation; it’s not funny. I suspect the joke, in fact, was funny. The Russian jokes don’t translate well. That’s what I want you to ask him.

ROBERTS: Will do.

COWEN: Another thought I had on the question of how is this not quite a Russian novel though it’s in the Russian language. If I think of Tolstoy a lot in Russian culture — he even says this about Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Scriabin — it’s fanatical of different sorts. Obviously, Bolsheviks were fanatical, and this novel is extremely anti-fanatical. It’s like Montaigne in France. It’s like Chekhov is his model for how to be an anti-fanatic. So part of what he’s doing, I think, is trying to retell Tolstoy, but from a humanist, anti-fanatical point of view.

ROBERTS: I feel a certain fanaticism about, certainly, Solzhenitsyn, certainly about Dostoevsky. I can think of a few things that are fanatical about Tolstoy. What comes to mind?

COWEN: Well, his views on everything were extreme.

ROBERTS: It’s true.

COWEN: Beethoven, Shakespeare, religion, property. It’s hard to think of a more fanatical human being.

ROBERTS: Sex, God, marriage. It’s true. It’s true.

COWEN: He’d make a great podcast guest, but where would you even start? Dostoevsky, clearly a fanatic from the biography, from his works. If you read Armenian Sketchbook, which is also a great short book to read by him, he [Grossman] just seems so much not a fanatic.

That’s the most inspiring thing for me about this novel, that you can be, for him, committed to principles and morality and not be fanatic. He’s pulling that from Chekhov. When you’re from the smaller part of the empire you’re probably going to be less fanatical. It’s a bit like Americans and Canadians, perhaps. That, to me, really shone through in Life and Fate, the anti-fanaticism.

ROBERTS: Let me ask you a personal question. I really like that, by the way. It’s a certain detachment, is the way I would describe it. His anti-fanaticism takes the form of a detachment of the observer who hovers over his characters and describes them calmly without overdoing it. I’m less fanatical than when I was younger. Would that be true of you?

COWEN: Of course. It’s true for almost everyone.

ROBERTS: Is it?

COWEN: Especially if you have libertarian roots. No, it’s not true of almost everyone. But if you have libertarian roots, you either go crazy or you become less extreme, right?

ROBERTS: What do you mean, “right”? Expand.

[laughter]

COWEN: We each know some people who just went crazy, often in non-libertarian directions. Some of them become, oddly enough, fans of Putin, while we’re on the Russian topic, or they just stop believing in scientific argument and discourse. The saner thing to do — and you see this with many people from the progressive left as well — is just to become more moderate, more uncertain, to have better epistemic practices and take a broader swathe of history more seriously, and I think Grossman is doing that.

How much of history he’s taking seriously, not just the one point in front of his eyes, the Battle of Stalingrad, but the AI section — whether you agree or not, he’s looking to the future. He’s definitely looking for the Russian and Soviet past as well, the Ukrainian past, Jewish history, the Hebrew Bible. It’s spanning a lot. That’s one reason why I think it’s epistemically pretty non- or anti-fanatical and pretty rational.

ROBERTS: I have a couple fanaticisms. I’ve got my libertarian flavor and my religious observance. They’ve both become tempered in some dimension as I’ve gotten older. I don’t think it’s to avoid insanity, by the way.

COWEN: It wasn’t why you did it, but if you hadn’t done it —

ROBERTS: Maybe, but I’m curious —

COWEN: The people who don’t do it can just get worse, right?

ROBERTS: I’m curious why you think that is. I don’t think it’s true, by the way. You did suggest it might not be. It’s not obvious to me that people get less fanatic as they get older. In fact, supposedly as people get older — it’s not my personal experience; I’m grateful for that — but a lot of people, when they get older, just get crankier, and they get more obsessed with their obsessions, more fanatical about their fanaticisms. I think I’ve been spared that. But why do you think that happens?

COWEN: I think I should have said it’s a bimodal distribution, that you go one way or another. Look at it this way: In the simplest Bayesian model, your views should be a random walk, that the recent evolution of your views shouldn’t predict where you’ll end up tomorrow. But that’s not the case, really, with anyone that I’ve ever met. There’s some kind of trend in your views. You’re either getting more fanatical, getting more moderate, getting more religious, more or less something.

And that, to me, is one of the most interesting facts about human belief, is how hard it is to find belief as a random walk. So, what’s wrong with all of us? If you’re getting more moderate all the time, that’s wrong too. That’s a funny kind of, you could say, almost fanaticism, where you ought to say, “Well, I see the trend so I’m just going to leap to where I ought to be.” Then the next day, maybe 50 percent chance I’ll take a step back toward being more dogmatic or less moderate. But again, that’s not what we see from the moderates either.

ROBERTS: I wonder how much of it is the fact that it’s really convenient to have a system, gives you something to shove into the box. You’ve got this black box that you take the world’s events and you’ve decided how they should be processed. Then something new comes along, and you know how to deal with that because you’ve got this box; you’ve got all these great examples from the past.

At some point for me, I just started thinking that maybe the box doesn’t work all the time. I think a lot of people love the box. It’s a great source of comfort, whether it’s religion or ideology or other things. Maybe there’s just something peculiar about me. When you’re younger, certainty is deeply comforting because the world’s a bit too complicated to deal with. It still is, but I’m just less certain.

COWEN: There’s also a more charitable interpretation of what you’re describing. Think of yourself as working through problems, which is fine. Working through problems takes some time. You can’t every day pick up a new problem. The problems you’re working through as you — I wouldn’t say solve them, but as you somewhat make progress on them — that’s going to give you some persistence in the deltas of how your beliefs change.

I’m not sure — the pure Bayesian model might just be wrong. It’s so far from actual human practice. Maybe we shouldn’t just damn humans for not meeting it, but realize there are structures to how you work through things, and they are going to imply certain trends that go on for periods of time.

ROBERTS: Want to say anything else about this book, about will it persist with you? Will you think about it?

I’ve had a number of the stories and vignettes I think will stick with me for a long, long time. Many, many of them that I loved, I did not talk about. Listener, you will have to read them for yourself and make your own list. But this book will haunt me. Part of it’s because I’m reading it recently. I’m not haunted by a lot of the books I read when I was younger because I’ve forgotten most of the haunting parts, and I read this recently. It’s quite an achievement in that way, I think. It will last with me.

Do you want to add anything else?

COWEN: You’re living under wartime conditions in a way that I am not. I would just say my reading opportunity costs are very high for me to read an 872-page book twice in a row and be glad I did it. There’s no higher endorsement I can give to a novel than that.

ROBERTS: My guest today has been Tyler Cowen. Tyler, thanks for being part of EconTalk.

COWEN: Russ, thank you for thinking of me for this and thinking I might be crazy enough to actually do it. It’s been a great, great pleasure, both the reading and the chatting with you.

ROBERTS: Ditto.